Midmorning on a Monday is not peak time for door-to-door politicking, and in the leafy Philadelphia suburb of King of Prussia, most doors are locked and windows shuttered. But for members of the Koch army, the campaigning never stops.

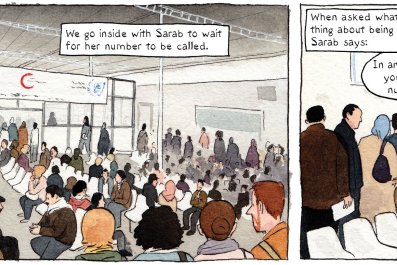

Local field director Jeremy Baker and brothers Chris and Ed Saterstad are one of several teams out in Montgomery County and neighboring Bucks County on this sunny September day. Each of them is equipped with an iPad mini, strapped to their wrist, and they refer to them constantly—to review their digital "walk books" and determine the doors on which to knock, to bring up the script they read to the people who open those doors, and to tabulate the responses they get. All this creates ever more data points for the vast trove of voter information the Kochs are building. For Newsweek's benefit, the three 20-something men are walking through this Upper Merion neighborhood. Usually, they run.

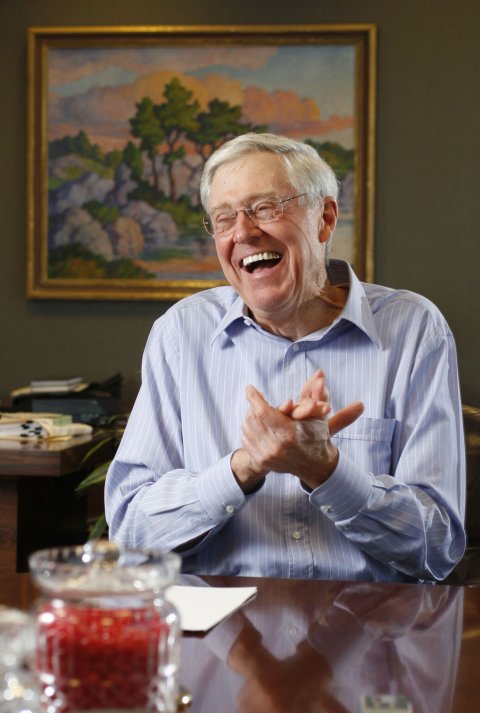

"Field teams are at close to 3,000 doors a week, between staff and volunteers," boasts Beth Anne Mumford, Pennsylvania state director for Americans for Prosperity (AFP), a conservative grass-roots advocacy group funded by the billionaire industrialists Charles and David Koch and their allies. Koch Industries is the second-largest private company in the country, according to Forbes, a $100 billion conglomerate of oil refiners, fertilizer makers, paper products producers and equipment manufacturers. The brothers also are a virtual ATM for a vast network of conservative organizations reshaping American politics.

As they have for many years, the Kochs are once again pouring money into a few Senate races in 2016, bolstering their GOP allies. But this time around, they have refused to bankroll the party's presidential nominee.

It's no secret the Koch brothers don't dig Donald Trump and have made it clear, despite repeated entreaties, that they will not be unleashing their formidable political network on his behalf. Mark Holden, the general counsel for Koch Industries, told Politico in May that the brothers would support only a candidate who "did not engage in personal attacks and mudslinging." Not only does Trump not fit that bill, but he also mocks some of the central tenets of their free-market, libertarian-leaning philosophy, most notably on trade and entitlements.

Some activists within the Kochs' network of advocacy groups, however, do not appear to have gotten the memo. "We're Muslim, me and my family, but we're voting for Trump, because I just have a gut feeling," Mary Khalaf recently told me at the annual conference held by AFP. "My gut just says, 'This is the person.'" Khalaf, who runs what she calls a "wellness house" in Ogden, Utah, to help those suffering from stress or mental illness, caucused for Trump in Utah during the GOP primary and then started volunteering with AFP after visiting its booth at the Republican convention in July.

She's not an outlier. Newsweek spoke to more than a half-dozen AFP conference attendees, and not one expressed strong opposition to Trump. And these are the Koch network die-hards—volunteers who took buses from places like North Carolina down to Orlando, Florida, to hear speakers extol the cause of "advancing freedom." The Kochs and their allies have not explicitly condemned Trump, nor have they directed their supporters to vote against him. Still, his popularity among rank-and-file conservatives is a vexing problem for the Koch boys and their crusade to shrink government. And it's not just his abrasive style that has them worried.

As Trump has laid bare during this campaign, "the ideology of the extreme free market"—slashing the social safety net, getting government out of health care and the like—is "not actually the core interests of rank-and-file conservatives," says Vanessa Williamson, a Brookings Institution fellow who has spent years studying the Tea Party and other conservative movements. At the grass-roots level, conservatives are apt to defend their government-funded Medicare and in the same breath lament Obamacare's "socialism." Abstract small government principles don't excite them nearly as much as demagoguery on immigration. And they don't see any contradiction in attending an event underwritten by the Koch brothers and then rushing home to plant a yuge Trump sign in their front yard.

Members of the Koch network acknowledge the challenge. "One thing that the last 15 months has taught us: Just when you think you've won an issue within the base, you realize no issue is really ever won," AFP President Tim Phillips says with a wry smile. On free trade, which has come under attack from not just Trump but also liberals like Democratic presidential primary candidate Bernie Sanders, "we were complacent," he says. The mindset, as he describes it, was, "Oh, this stuff isn't going to work…. This was a battle that was won over two or three decades. We're fine." Entitlement reform is another area where there's been backsliding, Phillips says. "We thought it was settled orthodoxy; suddenly, it's not anymore!"

But if the leaders of the Koch-backed entities are panicking about Trump's ascent, they're doing a damn good job of tucking it in. They're playing the long game. Phillips seems confident that his organization will engage and train conservatives in a way that can "build a deeper reservoir of support for core issues," like trade, entitlements and tax cuts. That, in a sentence, is the whole ethos behind AFP and the rest of the Koch outreach efforts. And it puts them in a strong position to steer the Republican Party after the election, even if Trump wins.

No One Escapes From Trump Island

In his approach to politics, Donald Trump in many ways represents the inverse of the Koch brothers. The Kochs and their allies have sought to cloak their identities with layers of organizational subterfuge; Trump has built an entire presidential campaign around his personal brand. The brothers shy from bravado and media exposure (a Koch representative declined a Newsweek request for an interview); Trump thrives on it. And where the Kochs have built an extensive operation at the state and local levels, recruiting volunteers in 35 states and building alliances across the country, Trump is an island, with little infrastructure, few like-minded political allies and nothing in the way of a doctrine that might live on once this campaign is decided.

Trump's field operations are so absurdly bad, in fact, that in most battleground states he's relying on the Republican Party's staff and infrastructure to do all the basic outreach. Regardless, the real estate tycoon has been remarkably successful, but the Trump model is not easy to replicate, as would-be followers have learned. Frank Bruni detailed in The New York Times in August that not one Trump supporter running in a Republican primary this year won. The first member of Congress endorsed by Trump, North Carolina Republican Renee Ellmers, got thumped in her June primary.

Contrast that with the Koch network. Led by AFP, it has canvassers on the ground year-round in nearly three-dozen states, knocking on the doors of carefully targeted households. Those targets are dictated by a massive data operation built up in recent years under the aegis of Freedom Partners, the main funnel for money from Koch charities and affiliated donors to advocacy groups such as AFP. In 2014, the most recent year for which reports are available, the 501(c)6 nonprofit group made $88 million in grants to the group, its sister organizations and other Koch allies, such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Rifle Association Institute and the anti-tax Club for Growth. In 2015, the network created its Grassroots Leadership Academy, a boot camp on activism and Koch governing philosophy, run by another AFP affiliate, the Americans for Prosperity Foundation.

In Florida, home to one of AFP's largest chapters, the group now counts 14 field offices, nearly double what it had in 2014, and more than 200,000 volunteers (although an AFP representative says that includes everything from door knockers to people who've signed a petition on its website). "Our activist count has swelled since 2014, and a lot of that is because we didn't just focus on federal issues. We really engaged on the state level, on the county level, on things that mattered to folks, things that they could touch and smell and taste," says Chris Hudson, the AFP state director.

Indeed, that "all politics is local" mentality is a big part of its strategy to remake government. "I'm already more focused on the 2017 legislative session than I have even stopped to think about this federal election," says Hudson. That may be a nice way of saying the Koch brothers are willing to concede this battle to Trump, because they're confident they'll win the war for conservative hearts, minds and ballots.

Your Grass Roots Are Showing

For decades, Charles and David Koch intervened in politics from the top down—doling out millions to foundations, think tanks and politicians that espoused their small-government philosophy. During election years, they poured money into groups that ran "issue ads"—typically thinly veiled attacks against Democratic candidates. It gave them sizable influence among the elites, shaping the beliefs of conservative leaders and commentators, but not much cred among the masses. In a 2010 New Yorker article, Jane Mayer documented the Kochs' history of funding so-called grass-tops organizations—groups designed to look like they were fueled by grass-roots activists when they were actually fronts for corporate interests.

The Kochs have gone to great lengths over the years to conceal the nature of their vast political operations, which has riled critics. One of the most relentless of those, Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid, went after the brothers earlier this month yet again, complaining that "the Kochs and their dark money empire are flooding the airwaves with misleading and false advertisements" to push their "crooked oligarchy agenda." The "dark money" epithet refers to the fact that the Koch network is made up almost entirely of 501(c)3 and 501(c)4 nonprofit organizations that can accept unlimited funds and do not have to disclose their donors. So when most people see ads funded by groups such as AFP, they don't realize that a coterie of wealthy donors and corporate behemoths with billions of dollars to gain or lose from policy decisions was behind it.

Making things even more complicated, the Kochs have constructed a maze of nonprofits and trust funds with many different purposes and focuses, some which are not real organizations but essentially just conduits for cash, says Robert Maguire, an investigator with the Center for Responsive Politics, a political spending watchdog . Millions of dollars are funneled between them. "There is no other network of politically active nonprofit groups and super PACs that is as convoluted and concentrated as the Koch network," he says. "It was very clearly constructed by lawyers to make everything the network is doing as difficult as possible to track."

Maguire says AFP started out as just another Koch-funded purveyor of attack ads. Before 2008, he says, AFP "was this little organization with like seven million dollars." Fast-forward to 2014, when the group spent nearly $100 million, much of it on the midterm elections. AFP's growth was soon followed by the emergence of sister groups like the Libre Initiative, which is focused on Latinos; Generation Opportunity, targeting millennials; and Concerned Veterans for America, for former service members. "At first, these were just sort of other vessels to put money into, and then they would run ads," says Maguire, with no staff or physical footprint to speak of, just post office box addresses. But since 2014, they've shifted emphasis and started hiring employees, writing policy papers and building communities on social media. On Twitter, "it's no longer just the standard preprogrammed Reagan quotes four times a week," he says. Instead, it's "here's a picture of our volunteers in San Antonio knocking on doors."

That, he says, is a major shift in strategy: Win big by going small.

It's Their Party, and They'll Blow It Up If They Want To

Will it work? The Koch network has enjoyed some sizable victories at the state and local level. "We've had more progress on 'right to work' in the last five years than in the previous five decades," Phillips boasts. "We've seen a dozen and a half states do dramatic tax cuts." But it's unclear if the grass-roots operations are really what's behind those gains, or if it has more to do with conservatives' success in getting like-minded politicians elected as state legislators and governors. Since 2008, Democrats have lost nearly 1,000 legislative seats and a dozen governors' mansions around the country.

Incoming Florida House Speaker Richard Corcoran says AFP's activists in that state reinforced his colleagues' stand against the expansion of Medicaid in 2015 and against spending on corporate tax incentives this past spring. Corcoran says his members were "being pounded" by editorial boards, special interests and even other Republicans, but they weathered the onslaught with the help of AFP mailing and policy literature defending their stands.

Florida Chamber of Commerce President Mark Wilson, however, says the Koch grassroots influence in the state is exaggerated. The chamber is one of the state's largest political players, with scores of lobbyists on retainer, and Wilson says the state's legislators "don't really care about what AFP has to say," and regard it as "a heavily funded group that's not from Florida."

But that's not to say things won't change. Wilson knows the Koch network leaders are focusing on 2020 and 2024, not this election. That gives the network time to further build up its ground game and data operations, using its local interactions to identify who cares about what issues and to mobilize people.

The Koch-funded technology firm i360 manages all that data and produces those apps AFP canvassers rely on when they're knocking on doors. Its database is a vault of voting records, consumer data, census information and social media profiles on more than 250 million adults, i360 says, 190 million of whom are registered to vote. In today's high-tech politics, this kind of granular data is crucial for conducting the kind of targeted campaigns that win elections.

"They've been very transparent about what they're trying to do, and I think a lot of people don't believe them," Wilson muses. "They want to replace political parties."