Russian authorities can shut down the local branches of international nongovernmental organizations (NGO) deemed "undesirable," under a new law passed by both chambers of the Russian parliament and signed by President Vladimir Putin last week.

It is unclear exactly what kinds of organizations may be subject to the law, which its author says is aimed mainly at international corporations. But one member of parliament has already asked authorities to look into five NGOs, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Transparency International.

The law is the latest in a series of controversial decisions by Russian legislators, who in the past couple of years have passed laws forbidding "gay propaganda" and preventing American citizens from adopting Russian children. The parliament also amended a law on unsanctioned mass demonstrations, imposing huge fines on participants.

The "undesirable organizations" bill was introduced by Alexander Tarnavsky, who argued that it was a response to sanctions imposed by the U.S. and Western countries on Russian companies. He also said that the law was directed mainly toward big international corporations and that an organization would have to be really notorious to be designated "undesirable."

However, none of that can be inferred from the bill, the phrasing of which is rather vague. For one thing, the term "foreign nongovernmental organization" is never defined, and the criteria by which someone can end up on the list of the "undesirables" isn't defined either.

The process for dealing with undesirables, however, is described clearly—and the government doesn't even need a court order to close a suspicious NGO. The responsibility to decide if an organization "poses a threat to the Russian constitution or the national security" falls on the attorney general's office.

As soon as the office informs the Ministry of Justice of its decision to designate an organization as "undesirable" and the name of organization is published on the ministry's website, the organization's local subsidiaries have to cease operations and new ones can't be legally opened. Such organizations are forbidden to hold public events, work with any financial institution within the country, or publish and distribute any promotional materials. Moreover, anyone involved with an "undesirable" organization is subject to fines and, in the case of "repeat offenders," criminal prosecution.

Even though the author of the bill said in an interview with Russian website Meduza that its purpose was not to affect the Russian branches of international, nonprofit civil rights organizations, experts expressed concern that the bill could easily be used to silence opponents of the Russian government.

On Monday, just two days after Putin signed the law, a member of parliament named Vitaly Zolochevsky filed a request with the attorney general's office to examine whether five NGOs should be designated as "undesirable," including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Transparency International.

However, Tanya Lokshina, Russia program director at Human Rights Watch, doesn't take this particular threat seriously. "It's very likely that Zolochevsky did that to make himself better recognized," she told Newsweek. "And he's actually achieved some success, because now I finally remember his name!"

In fact, as Lokshina pointed out, two of the organizations that Zolochevsky asked to be investigated are not even foreign, which renders his request essentially meaningless. Still, she is concerned.

"The law is bad news for all the international organizations that work in Russia, and this is terrible news for Russian civil society," Lokshina said. "They want to isolate Russian activists from their international counterparts. The most important thing is that the law contemplates sanctions against Russian citizens that participate in the activities of the 'undesirables,' and it doesn't specify what kind of activities. It is obvious that it was created for selective use."

The "undesirables" law is in some ways a companion to another controversial law, which was passed in 2012 and demanded that all nonprofits that receive funding from abroad while being engaged in any political activities in Russia should officially register themselves as "foreign agents." (The language of the law vividly evoked Soviet times, as undesirables does.) While it is not yet known how the "undesirables" law will be enforced, there already have been cases involving the "foreign agents" law.

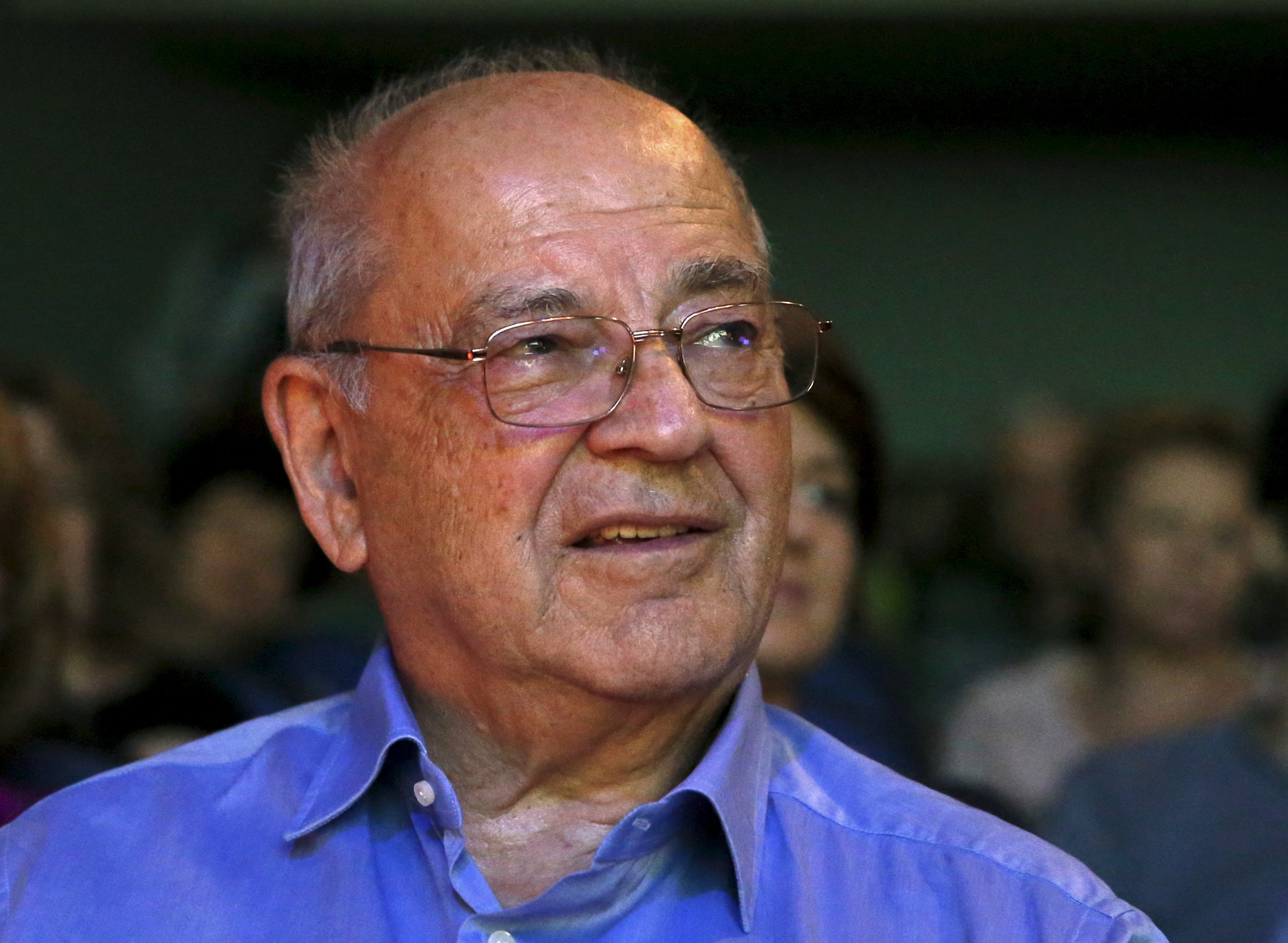

On Monday, the Ministry of Justice announced that the Dynasty Foundation is now included in the official list of "foreign agents," after an investigation uncovered certain unspecified "indications" in its activities. The foundation was created by Dmitry Zimin, the founder and president emeritus of Vimpelcom, one of the biggest telecommunication providers in Russia, who retired at the start of the 2000s to pursue philanthropy. Since 2002, the foundation has been spending more than $10 million a year to support Russian researchers and educational institutions. It also launched a publishing house that translated and published seminal books on modern science and organized the most respected nonfiction award in the country.

The Dynasty Foundation says that it does not have any foreign investors and that Zimin was its only sponsor. However, it was funded by money that Zimin kept abroad, which may have led Russian authorities to designate the foundation as a "foreign agent." (Asked about the money held abroad, Zimin noted that the Russian government keeps most of its money outside the country too.)

On Wednesday, the foundation's lawyer revealed to RBK that seven lectures that the foundation held in Moscow were the reason for considering its activities "political" and, therefore, made it eligible for the "foreign agent" status. One of the lectures, for example, was titled "How a Personalized Regime Has Developed in Russia."

"It's not unlikely that there were good motivations behind the foundation's work, but that doesn't mean that we shouldn't apply the law," Alexander Konovalov, the minister of justice, said at a press conference in St. Petersburg on Wednesday.

Even though "foreign agent" status doesn't prevent an organization from operating, it makes things considerably harder. For one, it has to include the fact that it is registered as a "foreign agent" in any work it produces. Also, the status imposes serious restrictions on collaborating with institutions funded by the government, such as public schools or universities.

The foundation can appeal to a court and ask for its status to be revoked, especially since in April the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation ruled that the law couldn't be applied to any organization that doesn't aim to influence state politics or the public opinion. However, Zimin already said that he will stop financing the institution unless the Ministry of Justice revokes its decision and apologizes. The foundation's board of directors will make a final decision on the organization's future at the beginning of June, but it's unclear how it can operate without the money.

"I won't spend my own money under the brand of some unknown foreign country," Zimin said to the press, obviously offended by the Ministry of Justice's decision. "I'm going deep underground. I'm so sorry. I'm almost crying."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.