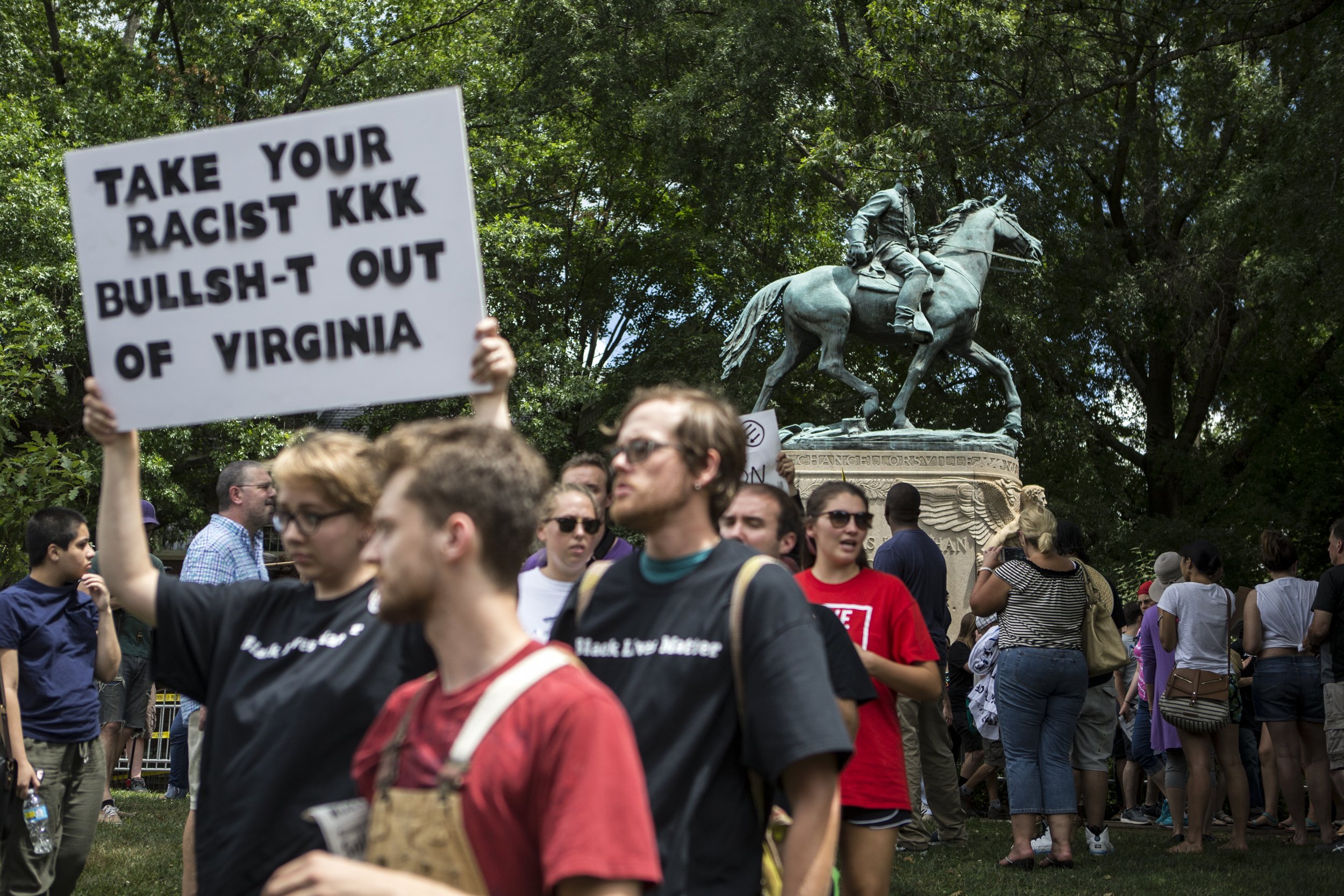

A statue of Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, has stood in Charlottesville, Virginia, for nearly a century. Now, it's at the center of the violence and racial unrest that has engulfed the Southern city since a group of neo-Nazis, white nationalists and other right-wing extremists marched on the University of Virginia campus Friday night.

The racist marchers had been angered by the city's vote to remove the statue from the spot in Charlottesville where it has stood since 1924. That decision is part of a larger trend in which Southern states are reconsidering long-standing public monuments that honor or romanticize the Confederacy.

Now, even Jefferson Davis's great-great-grandson—an outspoken defender of the Confederate president's legacy—says that the statue of Lee should be removed from public display.

"The [Confederate] monuments reflect a part of history that needs to be still preserved," Bertram Hayes-Davis, a direct descendant of the president of the short-lived Confederate States of America, tells Newsweek. But "if such monuments are on public property and they offend any part of our population, then they should appropriately be relocated to a place where that history can still be taught without affecting those who don't want to have that history."

As an example, Hayes-Davis points to a statue of Jefferson Davis that was removed from the University of Texas campus in 2015. It was subsequently relocated to the university's Briscoe Center for American History, where it's used for educational purposes. (The Sons of Confederate Veterans group sued in an attempt to keep the statue in place.)

Related: Jefferson Davis's great-great-grandson thinks the Confederate flag should go

"Putting it in the Briscoe Center, far from whitewashing or erasing history, puts it in the proper historical context," UT Vice President for Diversity and Community Gregory Vincent stated at the time.

A similar solution should be considered for the Charlottesville statue of the Confederate general, Hayes-Davis says: Put it in a museum, where it would be an artifact instead of a public symbol of Confederate pride. "If it offends anyone or creates anger or division in this country, we need to be able to put it in a place where those who want to learn the history can still view it," he says. "I think the debate's not about the memorabilia. It's about the understanding of our country's history."

Lee remains a cultural and military hero throughout pockets of the South where the Confederate flag still flies. But despite his celebrated name, the Confederate general was also a notoriously cruel slaveholder who helped lead the South's doomed effort to preserve the "peculiar institution."

Hayes-Davis remains outspoken as a public speaker on Civil War–era history, which he says is widely misunderstood, and previously served as executive director of Beauvoir, the Jefferson Davis home historic site in Mississippi. In 2015, after the Charleston church shooting, he argued that the Confederate battle flag should no longer be publicly displayed. Today, he declines to comment on the white supremacist groups specifically—or to say whether or not he supports President Donald Trump, who waited days before condemning neo-Nazis, white nationalists and white supremacists who gathered in Charlottesville.

Lately, Hayes-Davis has been involved in a reconciliation movement with the descendants of other 19th century historic figures, including Dred Scott and Sally Hemings.

In December, he attended the first Reconciliation Conference, an event organized by the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation in which descendants of Dred and Harriet Scott came face-to-face with the descendants of the men and women who enslaved their ancestors.

On Saturday, as unrest in Charlottesville boiled over into outright violence when a car plowed into a group of protesters, Hayes-Davis was serving on a panel discussion in St. Louis with family members of Scott, Thomas Jefferson and Justice Roger B. Taney. (The event was meant to honor the 160th anniversary of the day the Scotts were freed.)

"We have learned to respect each others' descendants and yet understand that history and say, 'We can get together, why can't you?'" he says of the gathering. "[We can] have a reconciliation and come together, not separate."

But that reconciliation—in Charlottesville and elsewhere—requires confronting the decades of trauma and racial violence that are invoked by images of the Confederacy. Scattered throughout the region, these statues and monuments continue to haunt the South and reveal racial animosities that persist 150 years after the war. In Nashville, for instance, protesters are now calling for the removal of a bust of Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, who joined the Ku Klux Klan during the late 1860s.

"Living in Montgomery, I'm surrounded by 59 markers and monuments to the Confederacy," Bryan Stevenson, a public interest lawyer who is founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, recently told Newsweek while discussing an exhibition on lynching and racial terror in America. "We don't have Martin Luther King Day, we have Martin Luther King–slash–Robert E. Lee Day. You can't create a healthy society when you celebrate and romanticize human rights violations, when you are indifferent to the trauma created by decades of human trafficking and enslavement."

"Reconciliation," Stevenson added, "means confronting the meaning of this iconography."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.