If you want to learn about the massive asteroid impact that triggered the extinction of dinosaurs, you might reach for dinosaur fossils. Or, it turns out, you could turn to a rather more humble form of scientific evidence: fish bones, teeth and scales each as small as a grain of sand.

That's the approach taken by the people behind a new paper published in the journal Science. In it, a team of scientists use the chemical fingerprint in what's euphemistically called "fish debris" to measure dramatic temperature changes caused by the massive asteroid impact about 65 million years ago. They say that the results could teach us what to expect from our own forays into the large-scale release of climate-altering gases.

"What happens when you crank up the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and maybe denude the landscape?" co-author Ken MacLeod, a geologist at the University of Missouri, told Newsweek. "This is a natural experiment for what happens when you twist the dials that hard." As to what that experiment showed, it's a grim picture.

MacLeod and his colleagues couldn't get a good look at the whole post-impact picture. In the immediate wake of the impact—on the timescale of a few years, temperatures plummeted worldwide. That so-called global winter was caused by aerosols flung high into the atmosphere reflecting the sun's light away from Earth. Because the winter was so abrupt, scientists struggle to pick up its signal in geologic records.

But the asteroid impact had a second, longer-lasting consequence: it vaporized a huge amount of carbon into the atmosphere. And once the haze cleared and sunlight could reach Earth's surface again, that greenhouse gas got to doing what greenhouse gas does best: turning up the heat. MacLeod and his colleagues suggest that in the location they sampled, it raised local seawater temperatures by about nine degrees Fahrenheit for 100,000 years.

That climate rollercoaster shaped what species survived into the present. "It must have had a severe effect, even more so when it directly follows an impact winter because it's two very stressful environmental changes directly following each other," Johan Vellekoop, a geologist at KU Leuven university in Belgium, who wasn't involved in the new research, told Newsweek. "It was an unpleasant time to be alive on planet Earth."

In order to figure out precisely how unpleasant a time it was, MacLeod and his colleagues looked to those humble fish remains. Team members dug a trench at El Kef in Tunisia, a spot chosen because it's one of the few places where scientists can all agree on precisely how layers of the Earth match up with specific years before and after the impact.

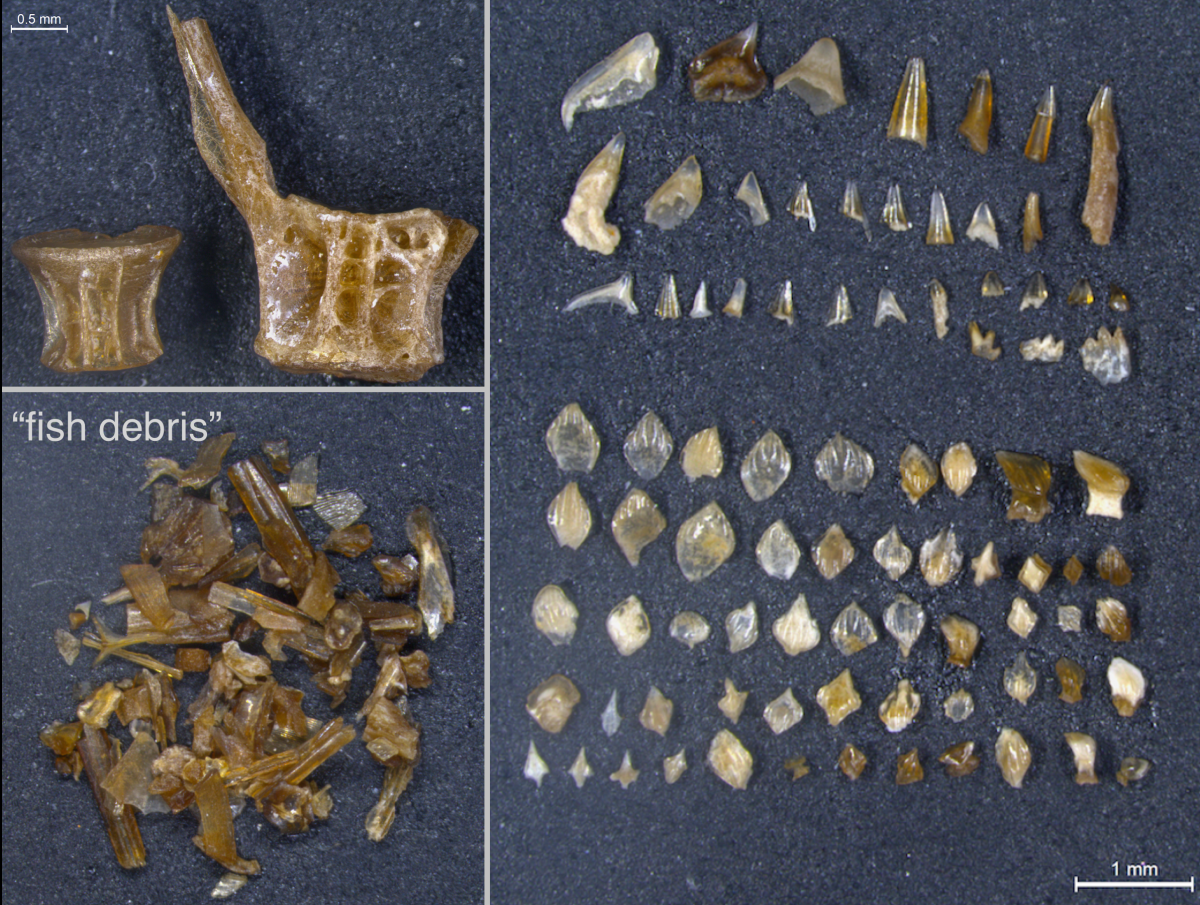

Then, they isolated the fish debris itself. "We start out with a rock, we wash the rock down to just the sand-sized grains," MacLeod said. Most of those, unsurprisingly, are rock or sand. Just one in 1,000 or 100,000 particles once belonged to a fish. But those tiny flakes of calcium apatite, the same material in your bones and teeth, act like time capsules for chemical signatures of oxygen.

MacLeod and his colleagues translated those signatures into temperature readings. It's not a foolproof approach for a couple of reasons. Right now, the measurements only reflect what was happening at one specific location, although MacLeod said he'd like to take the technique elsewhere. And because fish are talented swimmers, there's a chance that their movement has muddied the climate record.

Still, the study points to warming on a distinctly troubling scale, particularly as we face down modern anthropogenic climate change. "Even though those greenhouse gases were introduced over, let's say, a couple decades," MacLeod says, versus the two centuries we have drawn our carbon emissions over, "the consequence of that change to the atmosphere lasted for 100,000 years."

All that's left to figure out is precisely how big the pseudo-asteroid impact we're causing will be, and how long its effects will last.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.