The FBI is currently investigating Beijing's espionage in U.S. universities, as reports recently revealed that members of the Chinese military had attended Western schools while posing as students.

As a result, some schools are starting to look more carefully at the Confucius Institutes, nonprofit public educational organizations linked to Beijing that teach Chinese language and culture on university campuses across the U.S.

The Confucius Institute was named after a Chinese philosopher and teacher from the fifth century B.C., and the first opened its doors in the U.S. at the University of Maryland, 14 years ago. It was 2004, just four years after President Bill Clinton normalized trade relations with the communist country and one year before the U.S. recognized the emerging power as a"responsible stakeholder," a nebulous concept that suggested China was acting accountably on the global stage.

David Branner, an expert in Chinese language and translation, was leading the university's Chinese language program at the time. His department struggled to attract funding, but he wanted to keep the class sizes small so that students could get specialized attention. Branner sometimes wondered whether the university was committed to teaching Chinese language, and so its sudden decision to open a Confucius Institute, which was made without the consultation of the school's language department, surprised him.

"It was set up in secret. No administrator connected officially with Chinese instruction at Maryland heard anything about it until the opening ceremony was announced. It was a shocking end run around all of us," Branner told Newsweek.

Even more surprising was the fact that the Confucius Institute was helmed by a prominent Chinese physicist who had no experience teaching languages, Branner said. But the physicist had high-level connections to the Chinese government, and the institute quickly gained visibility under his direction.

"The Confucius Institute's funding grew rapidly, far outstripping theChinese programs. We were told that if we wanted any small part of that largesse, we would have to agree to certain programmatic changes that the Confucius Institute would propose," Branner said. "I was also told by a Confucius Institute employee that our study abroad program with Taiwan, which coexisted with programs to the People's Republic of China, would be an obstacle to support from the Confucius Institute."

Beijing views Taiwan as an official province of China, even though the island operates independently. Taiwan's sovereignty is a tense political issue that divides the government even in its capital, Taipei, and China pressures any allies that appear to recognize the island's statehood.

Shortly after the Confucius Institute opened its doors in Maryland, it offered to lend the university's language program a free Chinese language teacher. The staff assessed that the lecturer was poorly trained, and he spent most of his time collecting information about the Chinese language program instead of teaching, according to the faculty. Meanwhile, the official Chinese language program was increasingly sidelined, Branner said.

"The Confucius Institute at Maryland also held nominally scholarly conferences and research programs, sometimes on subjects related to language or sinology, but during my time there the Chinese language faculty was excluded," Branner noted. "I felt that was a form of punishment for our declining to submit to the Confucius Institute."

Ultimately, Branner determined that "language teaching was not the real point of the Confucius Institutes—the real point was propaganda." He also suspected that the University of Maryland was chosen as the site for the first Confucius Institute because of its proximity to the federal government in Washington D.C.

"I was always surprised that the people who brought Confucius Institutes to the U.S. or administered one here were not required to register under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA)," Branner said. "They have given the Chinese government a voice on American campuses and schools, and the Chinese government has admitted the Institutes were intended as part of a propaganda movement."

Some schools, like the University of Chicago and the University of North Florida, have closed their Confucius Institute after Republican Senators like Marco Rubio of Florida began publicly expressing concern.

The University of Maryland's Chinese language program still exists today. Minglang Zhou, the director of the program, told Newsweek that the Chinese language program doesn't cooperate with the Confucius Institute because the faculty opposed the idea.

Representatives of the school's Confucius Institute also said that they focus mostly on outreach and that the institute is "one of the top sites in the Northeast for testing Chinese language competence, and often collaborates with the Chinese Student Association to co-sponsor events with the Chinese Faculty Association."

Donna Wiseman, the director of the University of Maryland's Confucius Institute, said in an emailed statement to Newsweek, "The Confucius Institute at Maryland has a long-standing commitment to community outreach around Chinese language and culture."

"As part of our partnership with Hanban, we are responsible for making decisions about the programs we offer to the community and the extracurricular activities we coordinate on campus," Wiseman said. Wiseman did not comment on the accusations of espionage or influence campaigns leveled at the institutes.

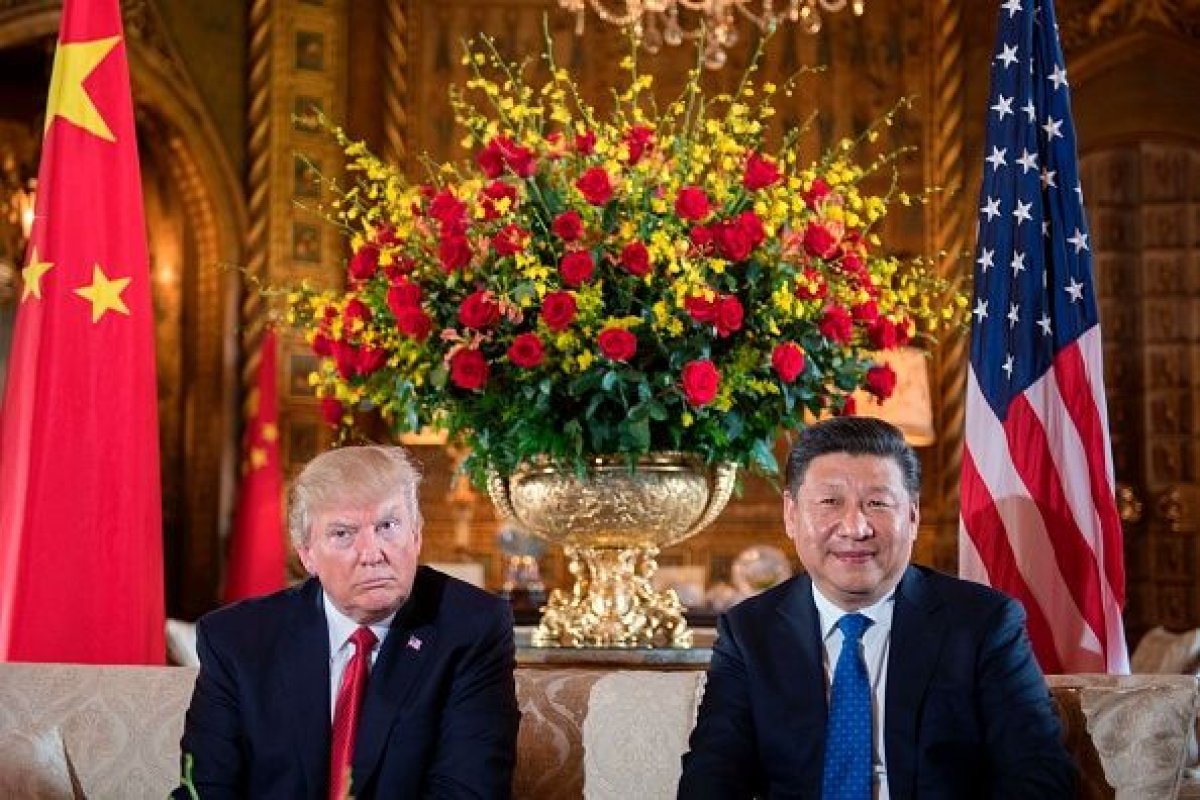

However, as the Trump administration launched a months-long trade war with China and began calling out Beijing for its efforts to influence U.S. public opinion, the Confucius Institutes have come under increased scrutiny.

Kirstjen Nielsen, the Trump administration's secretary of homeland security, said that China has long-standing "holistic influence campaigns" in the U.S. FBI Director Christopher Wray revealed during a hearing in February that the bureau is investigating instances of espionage at the Confucius Institutes. Meanwhile, during a closed meeting with reporters on October 4, national security adviser John Bolton claimed that the extent of Chinese influence efforts surpassed any he'd seen from other countries.

"The Chinese influence operation, much of what we know remains classified…but it's also a far broader effort to influence public opinions, through think tanks, through intimidating scholars," Bolton told reporters. "It's not like other countries don't hire lobbyists, but I've never seen anything like the scope of the Chinese activities."

One of the ways the Chinese government exerts its influence is through these language programs that simultaneously promote the political ideology of China's communist party, experts say.

According to the nonprofit National Association of Scholars, there are currently around 103 Confucius Institutes in the U.S. that claim to promote cross-cultural understanding and global education. Hosted on college campuses around the country, they are partially financed by the Hanban, an organization connected to China's Ministry of Education. The Hanban plays a direct role in deciding which faculty members can work at the institutes and what they teach.

"If you list the number of times a Confucius Institute affected academic freedom by tweaking information about Taiwan, you'd end up with a small book," Peter Mattis, a former CIA analyst who focuses on China, told Newsweek.

National Association of Scholars Policy Director Rachelle Peterson conducted case studies of 12 Confucius Institutes in New Jersey and New York and discovered that the Chinese government plays a hands-on role in deciding what will be taught.

"The teachers are hired and paid by the Chinese government. They send hundreds of free textbooks for use, and there is a good deal of censorship. They present the official Chinese version history, so everything from the Tiananmen Square massacre to current human rights abuses, students get a very one-sided view of events, and teachers are pressured not to upset the Hanban," Peterson told Newsweek.

"We know the Chinese government has many tools at its disposal. Professors that I interviewed felt like there was some possibility they were being listened to and that if they said anything wrong it would affect their ability to go back to China for research," Peterson continued.

It can be argued that these institutes are not very different from European cultural institutes like Germany's Goethe Institute or Spain's Cervantes Institute, which offer language and cultural programs worldwide. But experts, including Wray, have said the Confucius Institutes work to silence critics of China and recruit Chinese students to steal intellectual property from U.S. universities.

In May, GOP Senator Ted Cruz of Texas submitted a bill—known as the Stop Higher Education Espionage and Theft Act of 2018—that proposed to shed light on the way universities interact with these and other foreign entities, but the bill has not yet passed the Senate. Meanwhile, the Hanban has opened around 501 "Confucius Classrooms" in U.S. elementary and middle schools, and the number of these institutions continues to grow each year by leaps and bounds, according to National Association of Scholars.

The accusations of "holistic influence campaigns" center on the United Front, an official branch of the Chinese Communist party whose role is to rally Chinese citizens abroad and to make sure they fall in line with Chinese Communist Party policies. China analysts say the United Front is one of the most powerful branches of China's communist party, and its agents play an outsize role in China's governing politburo.

Aside from the Confucius network, there are estimated to be around 150 Chinese students and scholars associations (CSSAs) that play a similar role in universities across the U.S. Some analysts say these associations co-opt Chinese students studying in the U.S. and pressure them to feed information back to Beijing.

Many experts have agreed that Chinese influence operations are something the U.S. government should monitor, but opinions differ on the severity of the threat.

"There's no doubt that China and the Communist Party are engaged in influence operations and soft power using Confucius Institutes and CSSAs under the broad United Front umbrella. We need to pay attention to that, and we've been paying more attention to how they are being funded and supported," Christine Wormuth, a former undersecretary of defense for policy during the Obama administration and former member of the National Security Council, told Newsweek.

Nevertheless, Wormuth argued that these institutions more closely resemble soft power tools than aggressive influence campaigns.

"I think that the Chinese may be using them in ways that are more aggressive than the Alliance Francais, but I don't think they're hugely different. We see the activities on campus becoming more controlling, paying students to show up for Xi's visits, controlling the research agenda, it's a bit more overt and direct than the soft power you would see coming out of democracies. But I don't see them presenting a serious threat to our country or democracy at this point," Wormuth added.

Daniel Gang, a faculty adviser for a CSSA at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, said he doesn't believe the hype about espionage and influence campaigns.

"Trump has said all the students are spies, but that's ridiculous and impossible. I have lots of students, and I don't think so. Most of the students stay in the U.S. after they graduate, they don't go back, so why would they do that?" Gang told Newsweek.

But as U.S. universities become more expensive, the type of Chinese student arriving in the U.S. is starting to change, Gang said. The younger generation of Chinese students is more likely to come from a wealthy, well-connected family who benefits from the Chinese government's policies back home and supports the Communist Party's positions.

Many of the Chinese students involved in the CSSAs insist that they are only trying to bridge cultural divides and create a welcoming atmosphere in which Chinese students can thrive. But that hasn't stopped some officials, including top White House aide Stephen Miller, from advocating for the government to stop giving Chinese students visas. Miller reportedly urged the president to issue a moratorium on all visas for Chinese students in an effort to combat espionage.

Still, others argue the universities should work to ensure that their institutions can provide opportunities for Chinese students to study and express themselves without the undue influence of the Chinese government.

"The CSSAs are problematic if they get funding from the Chinese government and are reporting on Chinese students and voices that differ from Chinese government policies. That's the most damaging to our commitment to students. The U.S. educational experience is freedom to say what you think without fear of reprisal," Elizabeth Economy, the director for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations who is currently researching Chinese influence efforts, told Newsweek. "I think it's important to address this issue, but it's important to do it carefully, not in the frenzied McCarthyist approach of Stephen Miller to ban all Chinese students."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Cristina Maza is an award-winning journalist who has reported from countries such as Cambodia, Kyrgyzstan, India, Lithuania, Serbia, and Turkey. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.