At the end of March, mobile phone carrier China Unicom broadcast a 360-degree, 3D view of the Chongqing International Marathon that put viewers smack in the middle of the 30,000-strong scrum of runners. The images were four times sharper than the highest-resolution content available from Netflix.

The live stream—billions of digital bits of data per second—was 20 times faster than current cellphone networks built with 4G technology can manage. China Unicom was demonstrating 5G technology, the next big leap for mobile networks, built by Huawei, the Chinese telecom giant that President Donald Trump loves to hate.

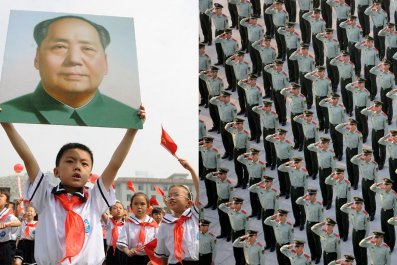

5G technology is arriving in the U.S. too—but not on networks built by Huawei, the world's largest manufacturer of 5G network equipment. The White House is pushing hard to keep Huawei from grabbing an insurmountable lead in wiring up the world with 5G, which is expected to usher in a new technological age of driverless cars, smart objects, remote medical procedures, new forms of advertising and other things nobody has yet dreamed up. "The race to 5G is on, and America must win," said Trump in mid-April. It's no secret that he is focused on China, led by Huawei.

But which 5G race can the U.S. hope to win? There are really three different races: one to provide the equipment on which the new networks are built; one to roll out the services widely; and another to develop the whole package—the software, devices, services and business processes that take advantage of 5G's blinding speed and near-instant responsiveness. The distinction is critical, because the U.S. has already lost the first race and may lose the second.

But the U.S. could still win the third race—and reap the main economic benefits of 5G. "The real race between the U.S. and China is to digitalize their economies," says Bengt Nordstrom, CEO of international telecom consultancy Northstream in Stockholm. "The rest is hype."

You won't hear these distinctions in the Trump administration's policies. The U.S. has already banned Chinese companies from building "essential" U.S. network infrastructure and threatened to ban Huawei components from all U.S. networks. The restrictions are pegged to suspicions that Huawei would give Chinese-government hackers "back doors" into its equipment.

Huawei denies any intent to build spyware, and there's no public evidence it ever has. But many experts agree that Huawei-built networks pose a big security risk. "U.S. tech companies have the right to refuse to cooperate with government requests to spy, to sue if they're being pressured and to disclose any spying to the media," says Timothy Heath, a senior international defense researcher at the Rand Corp. in Washington, D.C. "Chinese companies don't have those options. They're obligated by law to be amenable to exploitation by the Chinese government."

The Trump administration wields that argument to push the rest of the world into eschewing Huawei 5G equipment; it has threatened to sever intelligence ties with any nation that resists. So far that threat hasn't stuck. German Chancellor Angela Merkel is defiant. British Prime Minister Theresa May gave an official thumbs-up to Huawei 5G equipment (except for certain critical components). Most of Asia, Africa and Latin America have welcomed Huawei with open arms. Only Australia and New Zealand have cooperated with the U.S.; Japan decided to ban Huawei on its own.

Huawei, already far ahead on the technology, is undercutting rivals on price. Its equipment costs as much as 40 percent less than Nokia's and Ericsson's—its only competitors—and neither company can match Huawei's generous financing terms. Huawei's market share is now more than Nokia's and Ericsson's combined. The U.S. isn't even on the map: Not one U.S. company offers 5G network products or has announced plans to do so. And it's too late anyway: The market would be saturated before a new entrant could get products out the door.

What about the race to build 5G networks? On the surface, the U.S. appears to be neck and neck with China and tech-savvy South Korea. Carriers in all three countries (plus one in Switzerland) claim to have introduced early 5G services to a limited number of mobile customers, and Japan is expected to launch 5G mobile service soon. But the U.S. networks, offered by Verizon in 22 cities, have been derided for spotty coverage. U.S. mobile carriers, hampered by the ban on Huawei, show no signs of offering nationwide 5G coverage before 2021.

China is a year or two ahead on a 5G network rollout, experts believe. "The Chinese government can mandate it as a priority, and it has the financial resources to make sure it succeeds," says Gordon Smith, CEO of Sagent, a telecom company.

Once 5G networks are finally in place, however, the advantage is expected to shift. The U.S. maintains a strong lead in finding innovative ways to put Big Data to work for businesses and consumers, thanks both to tech giants like Google and Amazon, which spend billions on research, and a thriving tech-startup ecosystem. Leveraging 5G would create a digital world that reaches new levels of immersiveness, interactivity and realism and that is sensitive to every twitch of input from people and the environment. It would touch on video games and other entertainment; educational and advertising content; and the refrigerators, watches, buildings, store shelves and so on that cheaply zip sensor data to distant servers running artificial intelligence apps.

The economic impact of these services would be far more significant than building equipment and installing networks. The applications of 5G are expected to generate $4 trillion globally in the first two years alone, according to Wilson Chow, head of technology and telecommunications consulting at PwC China in Hong Kong. By contrast, the projected total worldwide market for installing 5G networks over four years is a mere $57 billion, according to industry research company IDC.

Perhaps more important, maintaining dominance in applications will allow the U.S. to remain the world's leading technology influencer. "Think of what the U.S. gained economically, politically and militarily from being the first to master internet technologies and how China had to struggle to catch up," says the Rand Corp.'s Heath. "5G is likely to play out in a similar way."

If it does, Trump, should he still be president, may end up thanking China and Huawei for laying the pipes that made it possible.