- California is expected to be hit by the "Big One," a massive earthquake along the San Andreas Fault, sometime in the next 100 years

- Droughts linked to climate change have parched many parts of the state, and wildfires and landslides risk making the destruction worse

- One scenario forecasts 2,000 fatalities, 50,000 injuries and $200 billion in economic damage

John J. Conlon was just a boy when a devastating earthquake struck San Francisco. But it wasn't only the quake itself on April 18, 1906, that seared itself into his memory: the most shocking events came immediately after.

"Thereafter, events were referred to as "before" or "after" the Fire," he said in an eyewitness account at the Museum of the City of San Francisco. "The earthquake, responsible for the fire, was a secondary matter. As a seven-year-old boy, free of parental control for three days, I enjoyed the excitement of the disastrous events around me without comprehending their consequences."

Now scientists are warning that those consequences could be even more severe next time.

The "Big One," a massive earthquake predicted to hit California along the San Andreas Fault, is expected to occur sometime in the next 100 years, and experts warn that climate change could make the already deadly event even worse.

With a magnitude of 8 or higher, the massive quake could cause widespread devastation for miles, specifically in populous cities such as Los Angeles. Climate change has little to no impact on the cause of earthquakes. However, scientists noted global warming impacts the wildfires and mudslides that follow an earthquake, and could double the fatalities and economic loss.

What Is the 'Big One'?

An earthquake of that magnitude on the 800-mile-long fault line could wreak havoc, destroy buildings, fracture lifelines like roads and aqueducts, and cause thousands of deaths. Destruction is expected to be specifically bad for those in basin cities like Palm Springs, Los Angeles and San Francisco, according to SanAndreasFault.org, a website dedicated to the fault line.

Dozens of earthquakes occur daily, but many are so small they are hardly felt or not felt at all. An earthquake with a magnitude of 6 or greater is considered dangerous. California rarely experiences earthquakes nearing an 8 magnitude, with historic records showing the state likely experienced two earthquakes nearing that severity—a 7.9 magnitude earthquake in 1857 and a 7.8 magnitude earthquake in 1906. It's possible, however, an earthquake exceeded an 8 magnitude in the 14th century based on data points along the fault lines.

Scientists are not sure exactly where or when the "Big One" will occur, only that it will eventually happen and that people should prepare.

In 2008, seismologist Lucy Jones worked with a team of scientists to draft the ShakeOut Scenario, a United States Geological Survey (USGS) story anticipating potential damage caused by an earthquake with a 7.8 magnitude. Jones' ShakeOut Scenario anticipates fatalities and economic loss from a massive earthquake if only the current preventative measures are in place.

Potential Damage Magnified by Climate Change

If the earthquake occurs on the San Andreas Fault, the ShakeOut Scenario estimates as many as 2,000 fatalities, 50,000 injuries and $200 billion in economic devastation as a result of it. Each aftershock, which could occur for months after the first quake, could add to those numbers.

The most dangerous part of an earthquake, aside from the tremors, are fires that often spark from urban sources following the quake. A large earthquake can break gas lines, damage electrical transformers and cause power lines to tumble to the ground. When electricity is returned, the damaged infrastructure can cause fires, which can be magnified by climate change.

In recent years, droughts have parched many parts of California and contributed to the far-reaching wildfires that are difficult to control and take days, weeks or months to suppress.

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions published a drought monitor map on Thursday that shows areas of drought in the United States. Central and southern California are some of the most severely impacted areas. The study said that climate change increases the odds of worsening drought by increasing evaporation rates, which dries out soils and by decreasing precipitation. The study found that annual precipitation in the southwestern U.S. has decreased since the beginning of the 1900s and the decrease is expected to continue.

If the area subject to the "Big One" is experiencing a drought at the time of the quake, fires following the quake and each aftershock could be even more damaging. Jones told Newsweek that the 2008 ShakeOut Scenario estimated the quake to ignite as many as 1,600 fires in addition to the mass casualties and financial loss expected. If California is experiencing a severe drought as it has in recent years, damage from fires could be worse than predicted.

"Climate change increases the likelihood we will not have a cool, calm day and will have extreme fire conditions," Jones said. "In that case, [damage] will blow up beyond double."

Jones also told Newsweek the most damage from the "Big One" is anticipated if the earthquake occurs during the Santa Ana winds, which produce strong, dry winds through southern California. The winds greatly increase the potential for fires, which are expected to double any fatalities and losses from the earthquake itself.

If the quake happens during the winter months, landslides could occur. The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions' drought study said climate models show global warming contributes to extreme periods of drought followed by periods of extreme precipitation, which increases the likelihood of landslides.

"This creates the need for expanded water storage during drought years and increased risk of flooding and dam failure during periods of extreme precipitation," the study said.

Jones said landslides would be much less damaging than fires. The ShakeOut Scenario estimates at least $100 billion in additional damage from fires. Meanwhile, landslides could cause $1 billion in additional damage.

The ShakeOut Scenario that Jones created anticipates that suffering would extend past the sheer number of injuries and deaths, as any road, track, pipe or sewer line crossing the fault would be severed by the quake. Damage to infrastructure could prevent emergency services from reaching fires or there might not be any water source to fight the fire.

People in the affected areas would be without power and water for a month or longer, and local businesses could crumble if owners don't have the resources to withstand that long without patronization. Even those in businesses or homes that have been constructed or retrofitted to withstand such a quake might face catastrophic clean-up. The ShakeOut Scenario anticipates that even if those buildings don't crumble, any unsecured items will fall to the floor and potentially break, leading residents to face a massive clean-up with no water or electricity to aid them.

Five major corridors pass the San Andreas Fault, including Cajon Pass and Interstate 10. The corridors are referred to as "lifeline corridors," as many mountains around Los Angeles prevent roads from traversing into the area. Affected areas would need to find alternate sources of water and could potentially be cut off from surrounding civilizations.

"Getting those things repaired and back to normal is harder to do when it's a larger area," USGS geophysicist Morgan Page told Newsweek.

According to The ShakeOut Scenario, when the "Big One" happens it will likely differ than the scenario presented since each quake "produces its own patterns of shaking and damage."

"However, the widespread, regional effects will be similar, and so will the long-term social and economic impacts," the scenario said.

The prospective impact also varies depending on where the quake happens. If it occurs closer to Los Angeles, the sandy basin those cities are built upon would magnify the damage. The amount of movement cities built on sandy basins feel is significantly more than those built on harder foundations, leading to the collapse of more buildings.

"Imagine sitting on top of a hard rock and you shake, it doesn't move as much as if you put that same structure on top of sand," Page told Newsweek.

How to Predict It?

The terrifying possibility of an earthquake with such a devastating magnitude influences scientists and civilians to look for patterns and any means in which to be prepared when it happens. However, Jones said the "Big One" is impossible to predict.

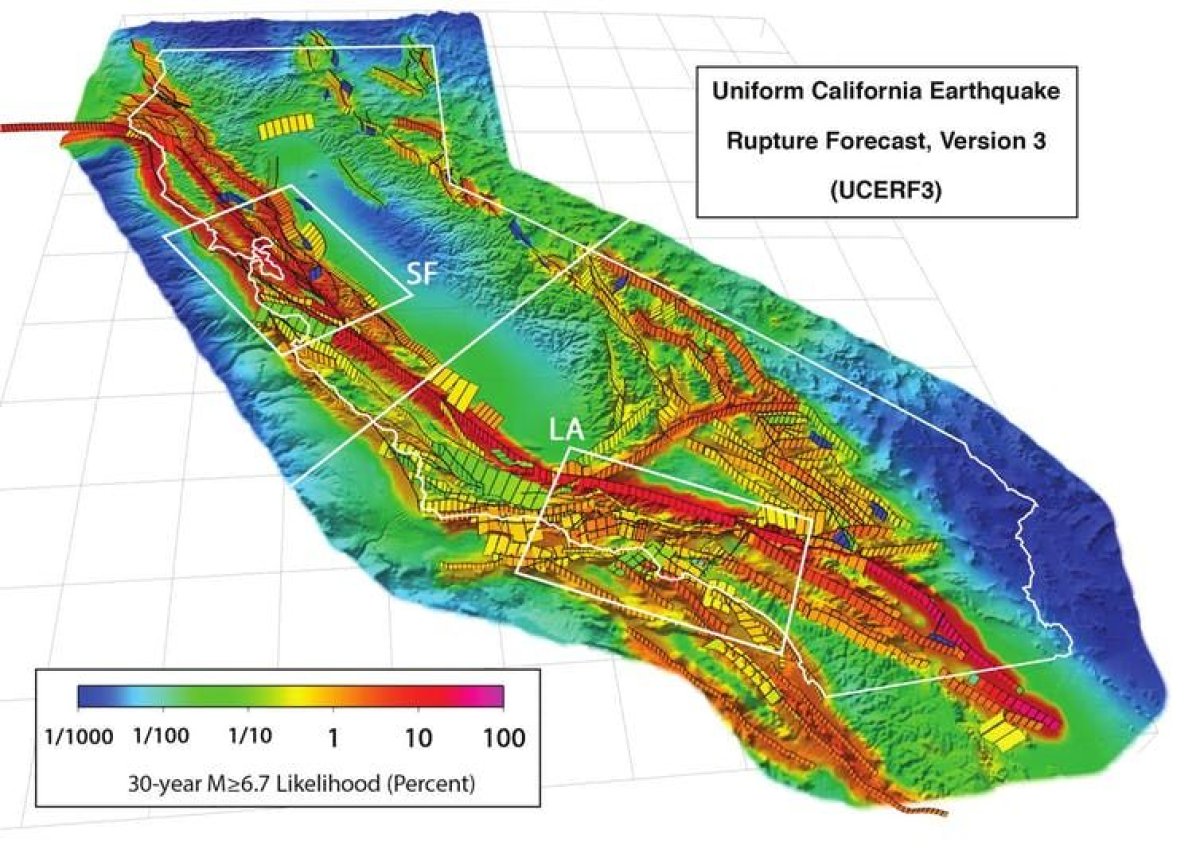

Page told Newsweek that current models show an earthquake with a magnitude of 8 or higher has a 7 percent possibility of happening in the next 30 years. Page said the predictions are based off fault lines along the San Andreas Fault that are prone to rupturing. One area that ruptured in 1857 tends to rupture every 150 years, indicating that it's overdue for one. Meanwhile, another area that saw a devastating rupture in 1700 is prone to rupturing every 300 years.

"Scientists don't like it being random. We want to find a pattern," Jones said. "[Common] human emotion is to find a pattern about dangerous things and try to make a pattern figuring out how to be safe. Even so, we have never found a pattern that actually sticks."

Jones added that scientists argue about time-dependent probabilities often, looking at dates of former earthquakes to formulate prediction models. However, she errs on the "completely random" end of the spectrum. The only time-related probabilities she follows is expecting the earthquake to hit in the next century rather than in the next year or decade.

Preparation

Although Jones said there's no way to prevent the "Big One," there are ways at-risk areas can prepare to better combat the devastation.

Page and Jones suggested prevention measures such as retrofitting vulnerable structures, such as un-reinforced masonry buildings or soft story buildings where the first floor of an apartment building is parking with the apartments stacked on top. The void space at the bottom level is not as strong as the rooms above and are more likely to collapse.

Smaller actions also can be taken, such as storing water, increasing volunteer preparedness and drafting collaborative plans.

"It's really up to us to make sure buildings and infrastructure are safe and reliable when it happens or we will have a much harder time," Page said. "An earthquake is inevitable but our response to the earthquake is not. We can control how safe buildings and infrastructure is."

About the writer

Anna Skinner is a Newsweek senior reporter based in Indianapolis. Her focus is reporting on the climate, environment and weather ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.