"The United States doesn't have a good history with urban projects," says architect Matthijs Bouw.

As proof, he points to the multitude of grim public-housing projects across the country. Theorists believed courtyards enclosed by tall towers would enhance quality of life, but nobody asked the people who'd be living there. Today, students learn about places like Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis and Cabrini-Green in Chicago as models for what not to do; city governments have already taken the wrecking ball to them.

"We've seen so many projects that failed because people didn't want them," says Amy Chester, who worked in former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg's administration.

Today, federally funded teams are attempting to learn from these failures as they try to protect low-income communities from storm surges and heat waves as the climate continues to change and weather becomes more destructive. Chester works for Rebuild by Design, launched in 2013 by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to help Northeastern cities recover from Superstorm Sandy—and prepare for future floods. To ensure that communities went all-in for Rebuild projects, HUD upended the normal infrastructure process: Instead of deciding what to build, municipal governments have to earn federal money by presenting ideas developed in close consultation with civic groups representing coastal communities from Connecticut to New Jersey.

Much of New York City's Lower East Side was battered by Sandy—apartment complexes lost power and heat for weeks, stranding residents in high-rise buildings that no longer had working elevators. When the waters subsided, a coalition of 38 groups—including residents' associations, advocacy groups, resource-rich charities like the Red Cross and corporate sponsors like Whole Foods Market—came together as LES Ready to organize immediate aid and develop long-term plans to better prepare the area for future environmental disasters.

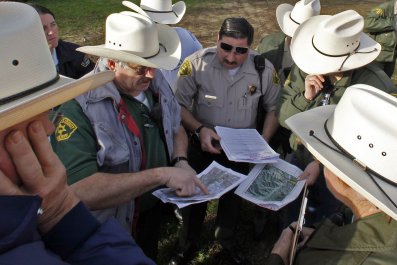

Later, when the city sought HUD funding for a large climate mitigation project in the area, HUD told them to "bring a business case," says Bouw, who was part of the project team. In other words, they had to prove that the project would not just prevent future water damage but would thrive. So the project management team sent designers to meet with LES Ready to make sure local residents and business wouldn't reject their plan.

At first, the coalition's chairwoman, Damaris Reyes (also head of the neighborhood housing and preservation organization Good Old Lower East Side), was wary that the promises the design team were making to waterproof the coastline would leave out her and her constituents. Initially, the city had secured only enough money from HUD for work on a more mixed-income part of the riverfront north of Montgomery Street; similar work on a lower-income area farther south would someday be phase two. Reyes feared that funding would dry up before the project was complete; she knew that if the first segment didn't work out, then voter backlash could make it hard for her and her neighbors to find money for protection from another lethal storm. She and other advocates convinced the city to go find more money before they broke any ground.

In response, the city reshuffled some funds and got financial assistance from another HUD disaster relief competition, ultimately committing an additional $176 million to protect Reyes's area. In the ensuing months, Bouw's One Architecture and his colleagues from lead design firm Bjarke Ingels Group, working with a large team, developed their design in frequent workshop-style meetings with residents. Instead of the customary manager from the mayor's office, locals decided what kind of amenities they had long lacked and where to put them. The stretch of East River Park in question had long been hard to get to and spottily maintained, even though the several thousand public housing tenants who live along the riverfront have few other places for outdoor sports or fitness.

So the end result includes safe pedestrian access to the park (over a busy six-lane road), as well as more athletic field upgrades and plantings—plus a few fancy perks, like an underwater window. "We're not just coming in with more meetings to tell people what we're doing," says New York City Office of Recovery and Resiliency Director Daniel Zarrilli. "We've been incorporating feedback into the design." Ultimately, HUD gave the city a $335 million grant to build a lush, sloping berm that can soak up water from storm surges and keep public housing towers behind it safe—all while appealing to those who live there.

This approach is a trend around the world. Facing the risk of longer and harsher droughts, the government in Singapore recently launched the "Active, Beautiful and Clean Waters" program: building or rebuilding 17 reservoirs to create a sustainable water supply—without alienating locals. "The intent was to make these places attractive. We had people, even children, involved with the design, and we turned [canals] into parks," says Khoo Teng Chye, initiated and led the effort as the former CEO of Singapore's Public Utilities Board.

The Marina Barrage, the first reservoir to open in the city center, can catch water from a sixth of the city's landmass and stands next to a 1,000-foot bridge. The barrage spurred the Public Utilities Board to come up with creative ways to get people excited about the structure. "We had workshops inviting the public to donate art and created a public outdoor gallery onshore," he says. "There was a lot of community participation compared to what could have been a fenced-off pump house."

In Rotterdam, Netherlands, the additional rainfall of an ever-wetter planet was wreaking havoc on outdated sewer systems, forcing the city to find new ways of storing rainwater. Government officials commissioned designers to work with locals on an urban design that would store storm water and make flooding "visible, audible and attractive."

The result was Water Square, which opened in 2013. It functions like a traditional plaza on pleasant days, slightly sunken from the surrounding brick patio and painted with bright blue geometric designs. On the edge of the square is a gutter shaped something like a playground slide that on rainy days captures the precipitation and dumps it into the plaza—turning it into a pool. Lights fall on the sloshing water, creating a public urban art installation. The firm that designed the square, De Urbanisten, says the gutters are wide enough to attract skateboarders on sunny days.

"The public is much more receptive to these plans if you tell them what the options are," says Jan Peelen, who works for the nation's Office of Infrastructure and the Environment. Peelen has found himself running more one-on-one meetings at public places and doing less of the top-down stuff the government usually does. The results have been surprisingly good. "We are seeing the number of appeals against projects going down," he reports. Not only that, the government is seeing the number of solutions go up. It turns out that residents sometimes have smarter ideas than those proposed by public officials.

For example, as part of the Room for the River project—which asks the hardy Dutch to admit that some areas in the Rhine River delta will flood too heavily to be livable in the near future—Peelen and colleagues proposed letting the Overdiepse Polder, in the agricultural area of Waspik, become a flood zone in order to avoid serious loss of life. The idea was that instead of simply waiting for traditional flood-plain designs like polders—low-lying tracts of land reclaimed from bodies of water and protected by dykes—to fail, they'd evacuate everyone in advance.

The cattle farmers there, predictably, didn't welcome the idea of abandoning their land. So they proposed "creating small hills" within the flood zone that they and their livestock could live on safely. Stan Fleerakker, the farmer who led this campaign, says it took some doing to get officials to treat citizens' input as valuable. "The first time we heard of the government's plan was in 2000, and it was last year that the compromise plan was ready," he says. "I'm 45, so it took a third of my life." But eventually, the project team moved to calculate how to build slopes higher than the new flood mark. Today, Fleerakker says his new home and his cows' new stables, 18 feet above the old site, satisfy all parties—including the cows.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Khoo Teng Chye is currently managing Singapore's "Active, Beautiful and Clean Waters" program. It has been corrected to clarify that while Khoo helped launch that program, he is no longer with Singapore's Public Utilies Board and thus is no longer managing the program.