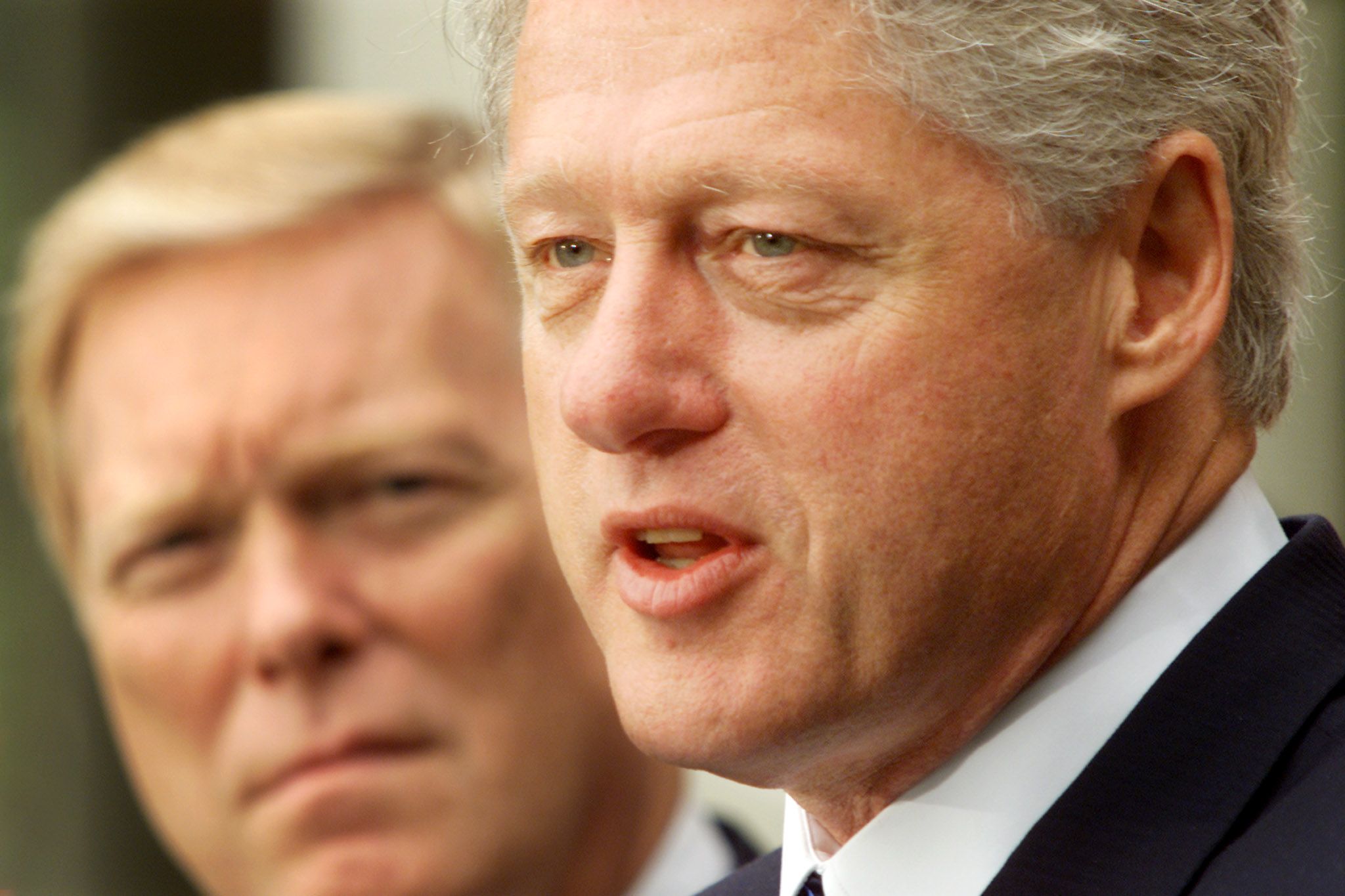

Newsweek published this story under the headline "Clinton's Hard Sell" on September 27. 1993. In light of recent events involving debates over health care, Newsweek is republishing the story.

Bill Clinton is betting on a card. When he offers his massive plan for health-care reform to a joint session of Congress this week, he'll show off a model of the "health-security card" he wants every American to possess. This wallet-size bit of plastic is high tech: computer-encodable, able to contain its owners' entire medical history. It looks a lot like the social-security card—reflecting the goal of a man who wants to enact the most sweeping entitlement since the New Deal. But it also looks like a credit card, raising the theory that Clinton wants to send another subliminal message: Charge it! Let's get the benefits now and worry later about how to pay for them. The health-security card actually is the centerpiece of two plans: Clinton's health-care reform and the approach to selling it. The first would reshape one-seventh of the economy, revise the spreadsheets of every business and household, and force a re-examination of the role of medicine in American life. The second is aimed at Washington's political operating room, which is already crowded with more spin doctors than any presidential primary. Here's a closer look at the White House sales strategy at the start of one of the biggest lobbying campaigns of all time:

Shout "Fire!" Clintonites claim that average Americans know all too well how unstable the existing system is. To make sure no one misses the point, the president and First Lady will spend much time highlighting "horror stories": citizens who lose coverage when they switch jobs, or contract an illness and are "dumped" by insurance companies. The message: This isn't about the laudable goal of "covering the uncovered," most of them poor. It's about you.

Use real numbers. The president thinks that voters will suspend their deep distrust of Washington in exchange for the promise of health-care "security." He'll lose that bet, worries a top White House insider, if he "comes off as just another tax-and-spend Democrat." So the numbers have to be valid, says former Ohio governor Richard Celeste, who heads the Democratic National Committee's lobbying effort on behalf of reform. "People have to know that it's going to be responsibly paid for," he said. But within the administration, some officials doubt whether the spending and savings numbers in the five-year, $700 billion Clinton plan add up. Ira Magaziner, director of the health-care task force, convinced Clinton that they do; officials at the Treasury and the Office of Management and Budget remain dubious. Clinton will have to find other sources of revenue besides higher tobacco and alcoholic-beverage taxes—or curb the benefits and the timetable for distributing them. His problems: Health-care interest groups already are clamoring to add benefits (more Pap smears, more generous psychiatric care) to the government-approved package. A benefits feeding frenzy would doom either the deal or any chance of getting the deficit under control.

Keep it simple. Not an easy task, given what one Senate health-care expert calls the "stupefying complexity" of the proposal. Clinton has to "make it understandable," says his polltaker, Stan Greenberg. There will be a single claims form, a symbolic promise of simplicity. The health-security card will embody the basic notions of the plan: Wherever you are, wherever you work, you're entitled to decent coverage, no matter what your illness. Polls and focus groups commissioned by the Democrats show that Americans like the quality of care they now receive—but worry that they will lose it when they change jobs or get sick. "Security" is the single most important word in the sales plan. The underwhelming slogan: "Health care that's always there."

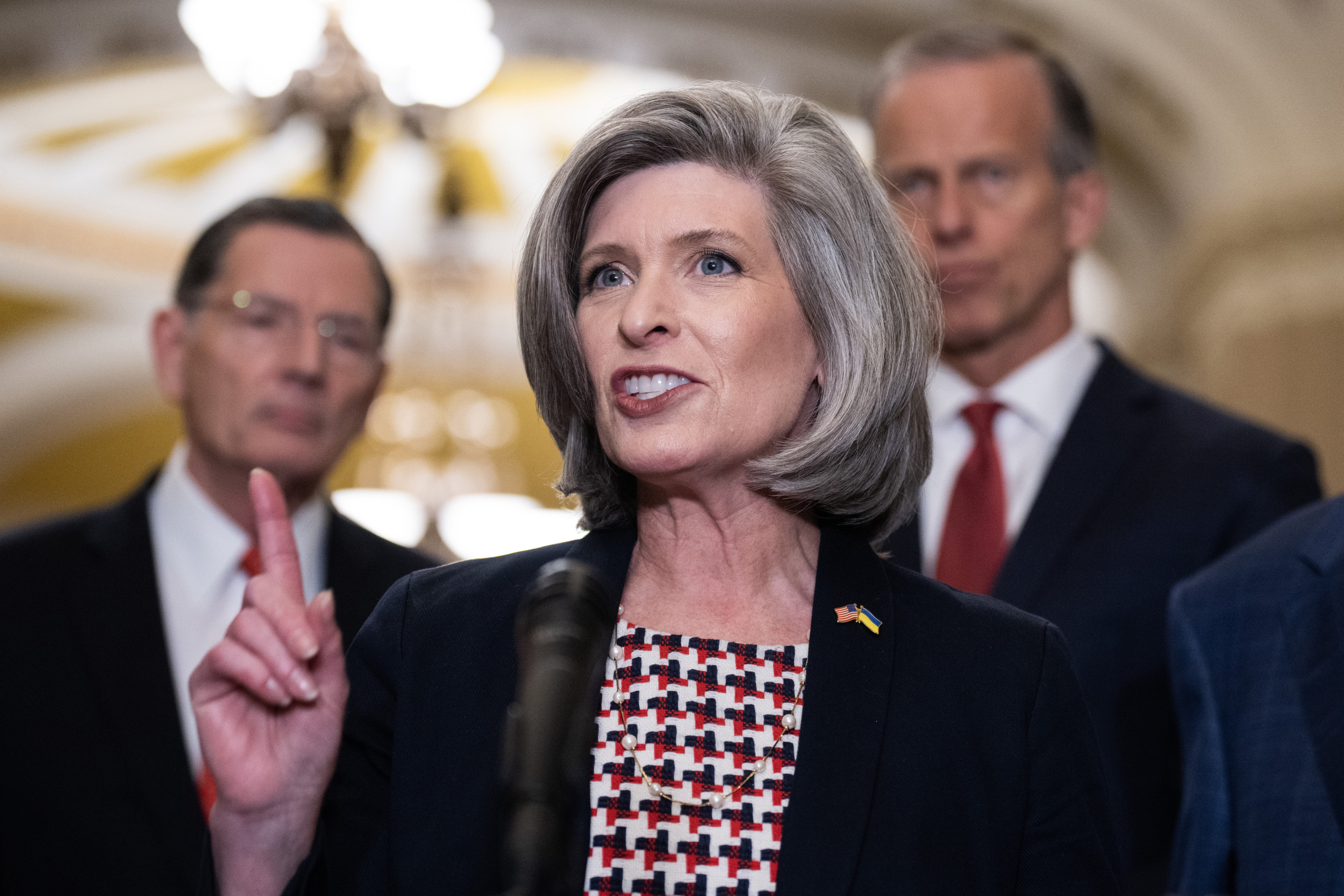

Keep the momentum. Clinton begins his sales campaign at an auspicious time. Memories of his debilitating budget "victory" have faded. He has enjoyed a blessedly uneventful run of non-news about White House screwups. Last week, Clinton's outstretched arms literally brought Yasir Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin together—for the president, a photo op of a lifetime. With a cheering section of three former presidents, Clinton delivered a convincing speech in support of the free-trade agreement. Even George Bush pronounced it eloquent. Clinton heads to the Hill this week with his "approval" ratings hitting 50 percent for the first time since April. And, by huge margins, polls show that voters trust Democrats—not Republicans—to deal with health care. "It's our issue," says Greenberg.

Court the Republicans. Unlike the budget, this can't be a Democrats-only deal. Happily for Clinton, it apparently won't be. Republicans have seen the polls showing that voters want action on health care. Moderate Senate Republicans, led by John Chafee of Rhode Island, have been working for years on a form of health-care reform that bears some similarities to the Clinton plan. Hillary Rodham Clinton has assiduously stroked Senate Republicans. Last week it paid off. Nearly a score of them—including Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole—showed up to unveil a "mainstream" plan of their own. It accepts two basic Clinton principles: the need for "universal" coverage and the need for the government to somehow "mandate" that coverage. The GOP plan would require individuals, encouraged by tax breaks, to buy coverage; the Clinton plan places the burden on employers. But the press conference was a little-noticed watershed: For the first time, a broad group of national Republicans accepted the idea of universal health care.

Claim the middle. The Clinton plan would create a vast new regulatory scheme—a National Health Board, regional "health alliances," detailed federal regulations on what all health-care plans must offer and the possibility of price controls. Clintonites answer the Big Government charge by pointing out that it could have been worse. There's the Democratic left's proposal, sponsored by Representative Jim McDermott of Washington, for a "single payer," Canadian-style system that would make Washington the nation's sole health-care insurer. It can't pass but is a useful foil. "We're trying to use the market, not abolish it," says Clinton media adviser Mandy Grunwald. The Republican right, led by Senator Phil Gramm, will tout a free-market, tax-break approach. The Clintons will argue that won't control spiraling costs.

Find villains. Every campaign needs enemies. The administration strategists have chosen theirs, based in part on focus groups and polls: "greedy" health-insurance companies that "cherry-pick," signing up only the healthiest, low-risk customers; pharmaceutical companies that take large markups on new drugs. The White House is trying to avoid attacking doctors and hospitals, and is desperately striving to soothe the concerns of small business by offering special tax breaks. But Clinton strategists claimed to relish a fight that broke out last week with the Health Insurance Association of America. The group aired an ad campaign preying on fears that Americans would lose the freedom to choose their doctors. If bureaucrats choose, "we lose," says a worried couple at a kitchen table. Clinton political adviser James Carvelle retaliated: "They ran the ad before they even saw the plan, and that's stupid. I would have paid them to do that." Maybe so, but the ad must have stung. A coalition of consumer groups, prompted by the Democratic National Committee, demanded that the ad be withdrawn. Late last week the DNC began airing its own "response" ad. "After years of denying people coverage and jacking up prices," it says, "the insurance industry is scared that change is coming."

Grass roots count. The health-care wars won't be a matter of 30-second ads. The real battle will be off camera. The White House is relying on the grassroots clout of key groups. Chief among them: the 32 million-member American Association of Retired Persons and the 14 million-member AFL-CIO. The administration won over the powerful AARP by promising senior citizens new prescription-drug coverage and long-term care. Those items are more costly than the iffy savings from proposed cuts in Medicare doctor and hospital fees. Big Labor's support was secured by dropping a proposal to immediately tax the most generous health-care plans—many of which belong to union members in industries such as auto and steel. So AFL-CIO president Lane Kirkland is balancing his opposition to Clinton on trade issues with loyal support on health care.

Let Congress do it. Clinton's strategists want him to play educator, explaining the issues, enunciating "principles" and leaving the tough final decisions to Congress. Fat chance. Viewers of C-Span soon will witness debates about which patients, illnesses and medical procedures to cover. Americans will see something new: health-care rationing discussed in public. By proposing to bring every medical decision into the arena of politics, the president may have started a process from which there is no turning back. If Congress cooperates, he ultimately will be held responsible for the results.

Special interests mobilize

As the Clinton administration prepares to sell a health-reform plan that promises to reorder one-seventh of the U.S. economy, armies of interest groups are gathering along the Potomac. Among the participants:

Doctors

The AMA is being cautiously supportive. Doctors want to be inside the tent to prevent price controls on procedures in fee-for-service private practice.

Insurance companies

The bitterest foes, except for a handful of giants already in the health-care network business. Focus groups show the industry to be public enemy No. 1.

Hospitals

For-profit hospitals don't like the plan, but are lying low for now. Public hospitals support the plan as an alternative to Medicaid and Medicare.

Drug Industry

Pharmaceuticals face tough new price restrictions. Seen as villains by seniors, the industry will go on the attack soon.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.