Elliot Aronson is frustrated.

A psychologist and professor emeritus at UC Santa Cruz, he poses a question: If someone invented a pill for children that decreased their anxiety about going to school, made them feel more included and happier, and helped them perform better on exams—and had no side effects—wouldn't we want to give kids that pill? Aronson believes he invented that "pill" in the 1970s, and no, it's not widely used, and no, he doesn't fully understand why.

After Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 13 and took their own lives at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, on April 20, 1999, Aronson had a provocative thesis about how to prevent the next Columbine. He thought Harris and Klebold had been excluded, bullied and taunted, which in part caused them to turn violent. The only true way to protect against another Columbine—at that time the deadliest mass school shooting in the nation's history—wasn't gun control, transparent backpacks, additional security or metal detectors, he believed. It was to reduce the competition and increase the cooperation and respect among students in schools. He had seen this utopian vision work in desegregated schools in the South nearly 30 years earlier.

In 1971, Aronson and a team of graduate students in Austin, Texas, were working with a school that had recently been desegregated. White, black and Latino students were in the classroom together for the first time in their lives. They bullied each other; there were fistfights. Aronson and his team developed a new structure for a fifth-grade classroom in which children were split into small groups of five or six, with each student responsible for teaching the others part of a lesson plan. The ones who were ahead learned to help the ones who were behind, and the ones who were behind caught up. They stopped fighting. Eight weeks in this type of classroom improves a young person's ability to empathize with other students, the team believed. It reduces bullying and taunting and makes students feel included. Absenteeism goes down. Kids are happier in school, and they also do better on objective exams.

Aronson named this method "jigsaw," published his research in Psychology Today and sent Xeroxed copies with an offer to do a no-cost, four-hour jigsaw tutorial to schools around the Southwest. "And then I sat back and waited for all the letters and phone calls to come in," he said. "I got a handful of interested people, but for the most part they weren't." He moved on to other research.

Until Columbine.

After the shooting, Aronson was sure his jigsaw could help prevent some future shootings. He wrote Nobody Left to Hate,a 208-page book on how to implement the program in the classroom to prevent violence. He created a website. He talked to a lot of reporters. He did an interview with The New York Times. Again, he waited for jigsaw to catch on. Again, it didn't.

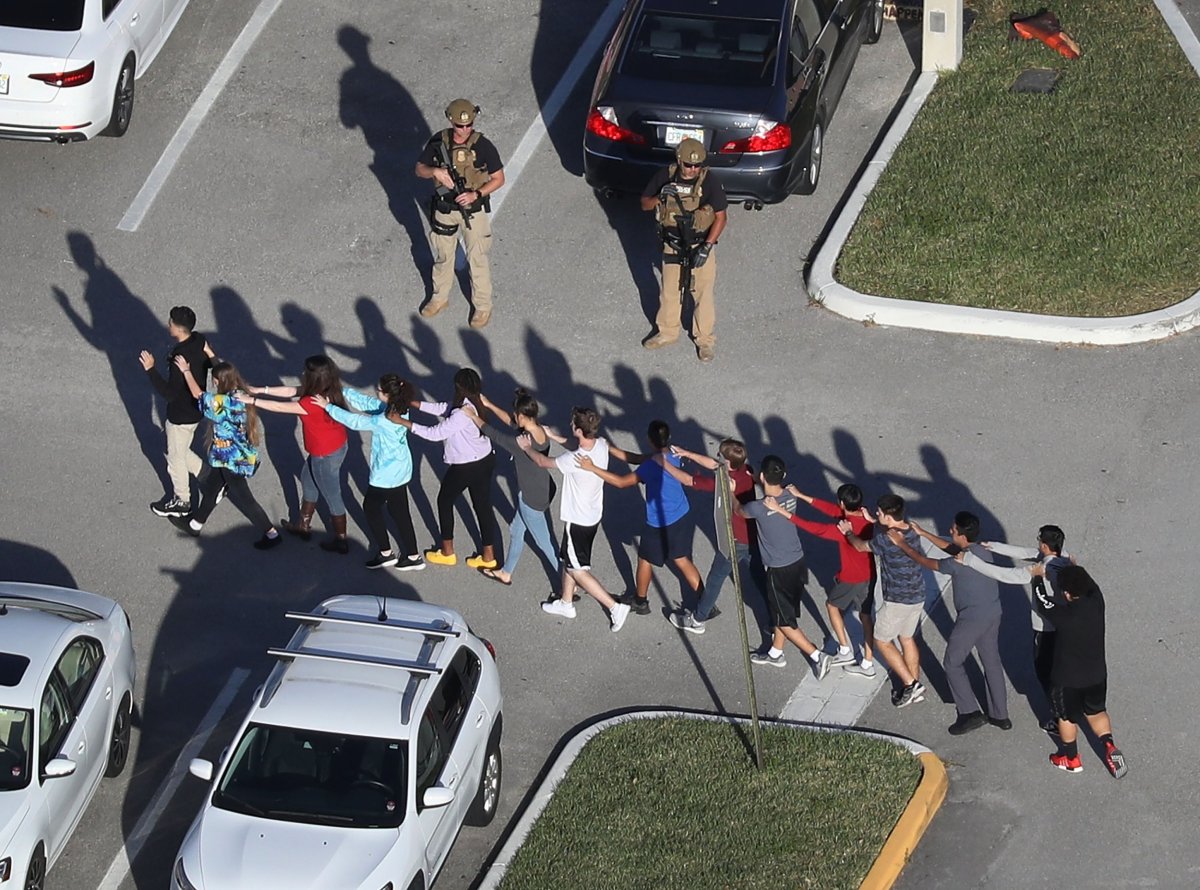

But the school shootings kept happening. From Columbine to the February 14 massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, there have been 208 of them, according to Denver's alternative weekly Westword. Activists are calling for gun control. Others want increased security or to arm teachers. In the lead-up to the 19th anniversary of Columbine, Aronson, now 86, talked with Newsweek about school shootings in the United States and possible ways to prevent them.

In Nobody Left to Hate, there are a lot of details about the Columbine massacre that mirror Parkland. One is that some authorities in both cases asked schools, kids and the community to report any suspicious behavior from other kids, thinking that would prevent more shootings. That's the opposite of what should happen, you write. Why is that?

An overwhelming majority of these rampage shootings that have taken place both before and after Columbine are due to these people being angry and feeling excluded at a time in their lives when inclusion is incredibly important: during those teenage years. One of my grandsons was in high school, inAlbuquerque [New Mexico], at the time of Columbine. He called me and said, "Hey, Grandpa, you'll never guess what happened at my school." They called an assembly, and the principal got up and told the kids, "If you notice someone, a loner, someone who doesn't sit with other kids in the cafeteria, someone who is excluded from baseball games, would you please report him to my office?" That's exactly the wrong way to go. And it's what's happening now. It's what happened after Parkland: "Let's be on the lookout for anyone who's a little bit different from the other kids. Who is excluded from things. Who nobody wants to talk to. Let's now give kids a good reason to support their exclusion of these kids. Let's further isolate these isolated kids."

To your point, it seems like teachers and administrators in Parkland knew to watch out for the alleged gunman, Nikolas Cruz.

In these days of Trump, we have to be especially careful about not overstating a case. I don't deny the fact that some kids are mentally disturbed, and it's not just situational. There are multiple reasons why somebody might go on a rampage. In the case of Parkland, I'm not certain, but I think [Cruz] was certifiably insane. I don't think anything can prevent that from happening except really good gun control laws. My understanding is that some kids did reach out to him and some kids did try to get to know him, and it just didn't work. Jigsaw may not have worked in Parkland.

You said that you think only better gun control laws could have prevented Parkland. You've previously written that gun control is a peripheral solution—it can help, but it won't get to the root of the problem. In 2018, is that still the case?

Yes, because the solution that I favor is one that makes people not hate each other. That's the central solution. I first started jigsaw because of school desegregation in Austin, Texas. The main thing is: How do we bridge the gap between people? If they don't hate each other, they're not going to shoot each other up.

Why won't gun control work?

You can take guns away from people, and that's a nice peripheral solution, but one that will never happen in this country—I'm convinced of that. The only thing that has changed in the 45 years since I first started to do jigsaw is that the NRA has gotten more powerful. Almost all congressmen are in the pockets of the NRA because they have a lot of money, and then there's the gun manufacturers...it's the worst aspect of capitalism in action. People love their guns. You can do some peripheral things, like keep certifiably crazy people from buying guns, but that doesn't mean that they can't get them.

Is there one peripheral solution that won't work?

Donald Trump is saying that we should arm teachers. Well, yeah, so that maybe they can shoot the shooter after he's killed 20 people, but well...he still killed 20 people. I think bringing more guns into schools is not really the answer.

....History shows that a school shooting lasts, on average, 3 minutes. It takes police & first responders approximately 5 to 8 minutes to get to site of crime. Highly trained, gun adept, teachers/coaches would solve the problem instantly, before police arrive. GREAT DETERRENT!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 22, 2018

Armed Educators (and trusted people who work within a school) love our students and will protect them. Very smart people. Must be firearms adept & have annual training. Should get yearly bonus. Shootings will not happen again - a big & very inexpensive deterrent. Up to States.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 24, 2018

When you see school shootings still happening in 2018, how does it make you feel?

I'm retired now, so I have nothing to think about but all of this stuff. Jigsaw—of all of the things I've done professionally—is what I consider my greatest triumph and also my greatest failure. It was a triumph in that I found a way to make school desegregation work the way it was intended to work: to bring black, white, Latino and Asian kids together, and make them respect and like each other more. And to be inclusive—that's what this country is about. And then to see that it was not universally accepted...teachers who use it love it, but educational innovations are slow to take hold. I was impatient. I thought, "Sooner or later, it will happen."

School should not be a place where we have to worry about our kids getting killed. The more I see things like Parkland, I do get frustrated and feel sad that I failed to do a good job of publicizing jigsaw because it really does work. And maybe someone who is good at publicity could have gotten jigsaw accepted on a wider scale. It would have prevented a great many of these school shootings.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Amanda Woytus edits breaking news. She previously worked at Time Inc., three Hearst magazines, and The Village Voice. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.