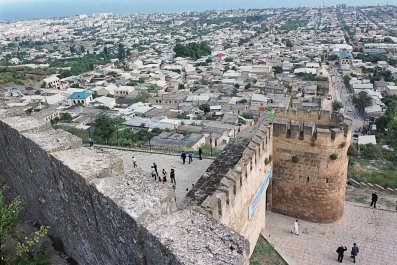

As modern Greeks, Brits and Hollywood hotshots continue to debate where the Elgin Marbles belong today, and as an exhibition of ancient Greek art runs at the British Museum, the original controversies that surrounded ancient sculptures have been as good as forgotten. The very things that obsessed the ancients – the stormy legal cases, jealous wrangling and courtesans of the artists who brought the stones to life in the first place – have been displaced by the dull "ours" or "theirs" of the dispute over their legacy.

The artists of antiquity would have been baffled by those who claim their marbles today based on national identity. Greece was no nation, and, despite their pride in being Greek, inhabitants of its various city-states were more likely to absorb the ideas of other peoples than distinguish between what was theirs and what was not.

And the sculptors had pressing preoccupations of their own. Modern artists are used to having their private lives dissected as part of the story of their work, and so were they. These were the earthy episodes that gave much of their work its colour.

Phidias, responsible for the hard thighs and touch-me torsos of the Elgin Marbles, had more than one male lover in his lifetime. In the rippling body of his Ilissos, the sculpture of a river god in the British Museum, one might see the handsome boys he took to bed, such as Pantarces of Elis, a champion wrestler. Phidias's combining of private and professional lives ultimately proved his undoing. After Pericles employed him to design the Parthenon artworks, comic poets are said to have stirred up malicious rumours that Phidias was pimping well-born women to be Pericles' lovers. The ladies were said to arrive at the Acropolis on the pretence of admiring his exquisite sculptures. How impressive that sight must have been is conveyed by the exhibition of the torso of the messenger goddess Iris together with a gilded reconstruction of Phidias's lost Athena Lemnia.

Placed inside the Parthenon, another Phidian sculpture of the goddess, colossal and cast in gold and ivory, caught the eye of Pericles' enemies, who persuaded one of the artist's assistants to accuse Phidias of embezzling its gold. His accusers weighed it only to find none missing but Phidias was imprisoned and exiled all the same, having riled people further, according to Plutarch, by impiously incorporating portraits of himself and Pericles into Athena's shield.

That did not stop him or other Greeks casting the gods in their own image. They saw the gods as bigger, more beautiful, more dazzling than themselves, but there was little to tell sculptures of divinities from those of mortals. On display is a Roman copy of a Greek bronze discus-thrower by Phidias's contemporary Myron. Poised, graceful, godlike in illusory perfection; the athlete was made to make the soul quiver.

A nude Venus – inspired by a 4th-century BC sculpture by Praxiteles – so irresistible a man is said to have left his semen on it, only half-heartedly tries to cover her chest and crotch.

In the goddess's feigned demureness the original model may have left her trace: ancient writers alleged that Praxiteles's famous Aphrodite was based on a prostitute, his lover Phryne. She won notoriety for her wealth and impropriety. When accused of inappropriate revelry and inventing a new god, she was excused only after her lawyer bared her breasts before the jury – just like Aphrodite in the sculpture.

If the British Museum's breathtaking, enlightening new exhibition throws more light on the exquisite mortals and immortals in art than on the artists themselves, it does not overlook how men capitalised on the artistic relationship between mortal and divine. Particularly fine is a bust of Alexander the Great, who believed he could disguise his short stature by tilting his head to one side. Lysippos, the Greek artist whose original bust inspired the Roman version on display here, was the only man Alexander allowed to sculpt his portrait. While other sculptors "made men as they really were, he made them as they appeared to be": tall, slim, and with wonderful hair.