A nuclear holocaust, like death itself, is something we'd rather not think about. So we don't, much, except when some figure of note starts talking about using hydrogen bombs to settle a problem. Someone like Donald Trump.

But the shock and outrage over Trump's recent loose talk about making Japan and South Korea develop their own nukes or dropping a bomb on the Islamic State militant group, also known as ISIS, obscures a more prosaic but arguably more imminent danger, according to a new documentary—a warhead going off by accident.

Command and Control, directed by veteran filmmaker Robert Kenner (Food, Inc.) and based on a best-selling book of the same name by Eric Schlosser, aims to widen the discussion about the threat posed by the thousands of nuclear weapons in U.S. hands (and, by extension, other countries' as well). Developed in concert with PBS's long-running American Experience series but slated for a limited September theatrical debut in New York City, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., the uncommonly gripping documentary focuses more on the frightening number of weapons mishaps than the missteps that could trigger a nuclear war. It skips over near-disasters involving panicky U.S. and Russian radar crews picking up incoming missile "ghosts" and nearly launching massive counterstrike orders. Instead, citing recently declassified Energy Department figures, it burrows into one of the "more than a thousand accidents and incidents involving our nuclear weapons," including the loss of eight warheads, one still buried somewhere in the soil of North Carolina.

Why any one of these incidents hasn't ended in a mass disaster is "pure luck," Schlosser says in the film. "And the problem with luck is it eventually runs out." Think about your laptop or car, he suggests. "Nuclear weapons are machines," he says. "And every machine ever invented eventually goes wrong."

Command and Control is hardly the first film or book to address atomic horrors, of course. Nuclear war has been a preoccupation of writers and filmmakers since the 1950s, when armed conflict with the USSR periodically seemed imminent, and American schoolchildren famously practiced "duck and cover" drills under their desks. In the 1960s, there was Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe. The 1980s brought WarGames, with its unforgettable climax of an exhausted computer running through all the possible nuclear-victory scenarios and concluding, "The only winning move is not to play." And a recent episode of FX's spy drama The Americans revisited the night of November 20, 1983, when 100 million people sat down to watch The Day After, ABC-TV's grim docu-drama on how a U.S.-Soviet nuclear exchange would play out. And so on.

In sharp contrast, a nuclear bomb accident nearly causing millions of fatalities has yet to capture the imagination of the doomsday moviemaking set. Kenner, however, has masterfully mined enough dramatic material from a near-catastrophe in Arkansas to fill a movie theater at the local mall.

"This powerful film," says Janne Nolan, chairwoman of the Nuclear Security Working Group at George Washington University, "is bound to spark a sobering and long-overdue national conversation about the costs and risks of maintaining a strategy of nuclear deterrence."

'It Scared the Hell Out of Me'

On the night of September 18, 1980, Robert Peurifoy, a scientist at the Sandia nuclear weapons lab, got a startling telephone call. A technician working high up on a Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile in a silo outside of Damascus, Arkansas, had dropped a 6-pound socket several feet, punching a hole in its first-stage fuel tank. The spewing fuel threatened to trigger a massive explosion that could have armed the warhead. The four-man missile crew had to exit from an escape hatch. Hours went by as desperate emergency techs, hampered by command delays, struggled to break their way back into the silo and fix the problem.

They were too late. A massive fireball erupted in the silo, obliterating the missile and ejecting its 9-megaton warhead, the most powerful in the U.S. arsenal, high in the air. It landed in a ditch about 30 yards away. "I knew I had to get to Damascus," Peurifoy recalls. "I knew that the warhead could have been armed, ready to fire."

Fortunately, it wasn't. The bomb-firing safety system held. Officials privately hailed the outcome as proof of the nuclear arsenal's safety over 30-plus years. But Peurifoy wasn't much calmed. Later, he says, "I read through all of the known accident reports, and it scared the hell out of me."

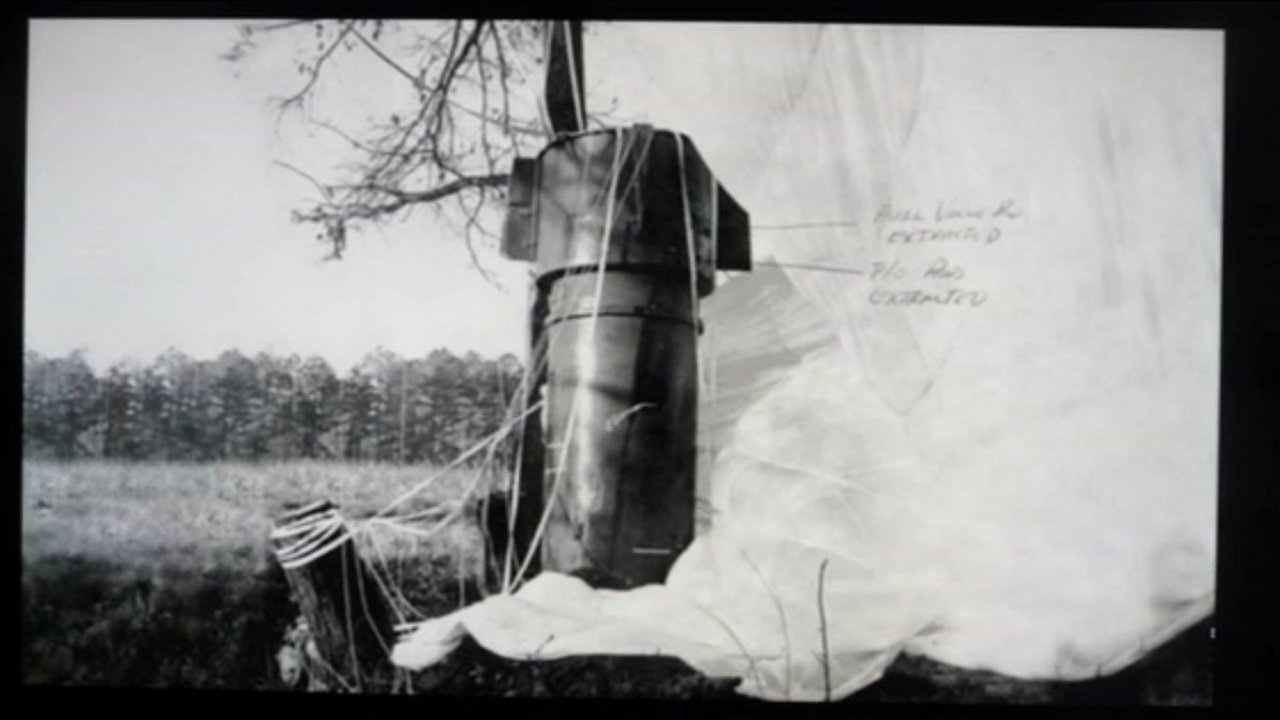

Two hydrogen bombs, for example, fell from a B-52 that broke up in flight and was spiraling down over North Carolina in 1961. One of the bombs "went through all of its arming steps to detonate, and when that weapon hit the ground, a firing signal was sent," Schlosser says in the film. "And the only thing that prevented a full-scale detonation of a powerful hydrogen bomb in North Carolina was a single safety switch."

Peurifoy describes the switch as not much more than something you might find on a desk lamp. "If the right two wires had touched," he says, "the bomb would have detonated. Period." The exploding 4-megaton warhead, about 267 times as powerful as the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima 71 years ago, would have instantly obliterated much of North Carolina and produced a mushroom cloud and deadly radiation plumes poisoning people and crops as far north as New York.

It didn't. But Peurifoy and a Sandia colleague, Glenn Fowler, became obsessed by the prospect of a fire accidentally arming a hydrogen bomb "by setting off its high voltage thermal battery," according to an account by William Burr, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive, a private research group headquartered at George Washington University. In the 1970s, the two became famous for putting on Pentagon briefings with burned circuit boards, annoying military officials who believed there was "enough safety," according to another Sandia scientist. "People were indignant that the labs would blow the whistles on themselves," he says.

Back then, there were 20,000 to 30,000 warheads in the U.S. arsenal, ensconced in the bomb bays of B-52s, in submarines, missile silos and foreign depots, not to mention the holdings of France, Britain, Russia and China. Many more would soon be in the questionable hands of India, Pakistan and eventually North Korea.

Harold Brown, a physicist who served as defense secretary in the Jimmy Carter administration, thought the immensity of the American stockpiles posed an imminent threat. "And we worried about that," he says in Command and Control. "We probably didn't worry about it enough." Warheads like the one ejected from the exploding silo in Arkansas "were both old and much more prone to accidents," he adds. The Carter administration kept them around, he says, with a kind of guilty smirk, because it "anticipated trading them off against Soviet heavy missiles in strategic arms negotiations."

After the night of September 18, 1980, there was one less to trade. Despite all the U.S.-Russia arms reduction talks, there are about 7,000 warheads left in U.S. hands, far more than needed for targets in Russia and China, critics say. "Nuclear weapons will always have a chance of an accidental detonation," says Peurifoy, who retired from Sandia in 1991 as vice president in charge of safety and reliability issues.

"It will happen. It may be tomorrow, or it may be a million years from now," he adds, "but it will happen."