North Korea has spent the first month of the year engaging in a frenzy of missile-related activity. Pyongyang has conducted seven missile tests in the first four weeks of the year, a number that already surpasses all of 2021. The latest test over the weekend involved an intermediate-range ballistic missile reaching a height of 1,242 miles before crashing into the sea after a 500-mile flight. Depending on who you ask, the latest launch broke a four-year, self-imposed North Korean moratorium on long-range ballistic missile tests. The United States reacted as it usually does whenever North Korean leader Kim Jong Un authorizes a test—condemning the launch, calling for a private U.N. Security Council meeting to discuss it and reiterating an offer of dialogue.

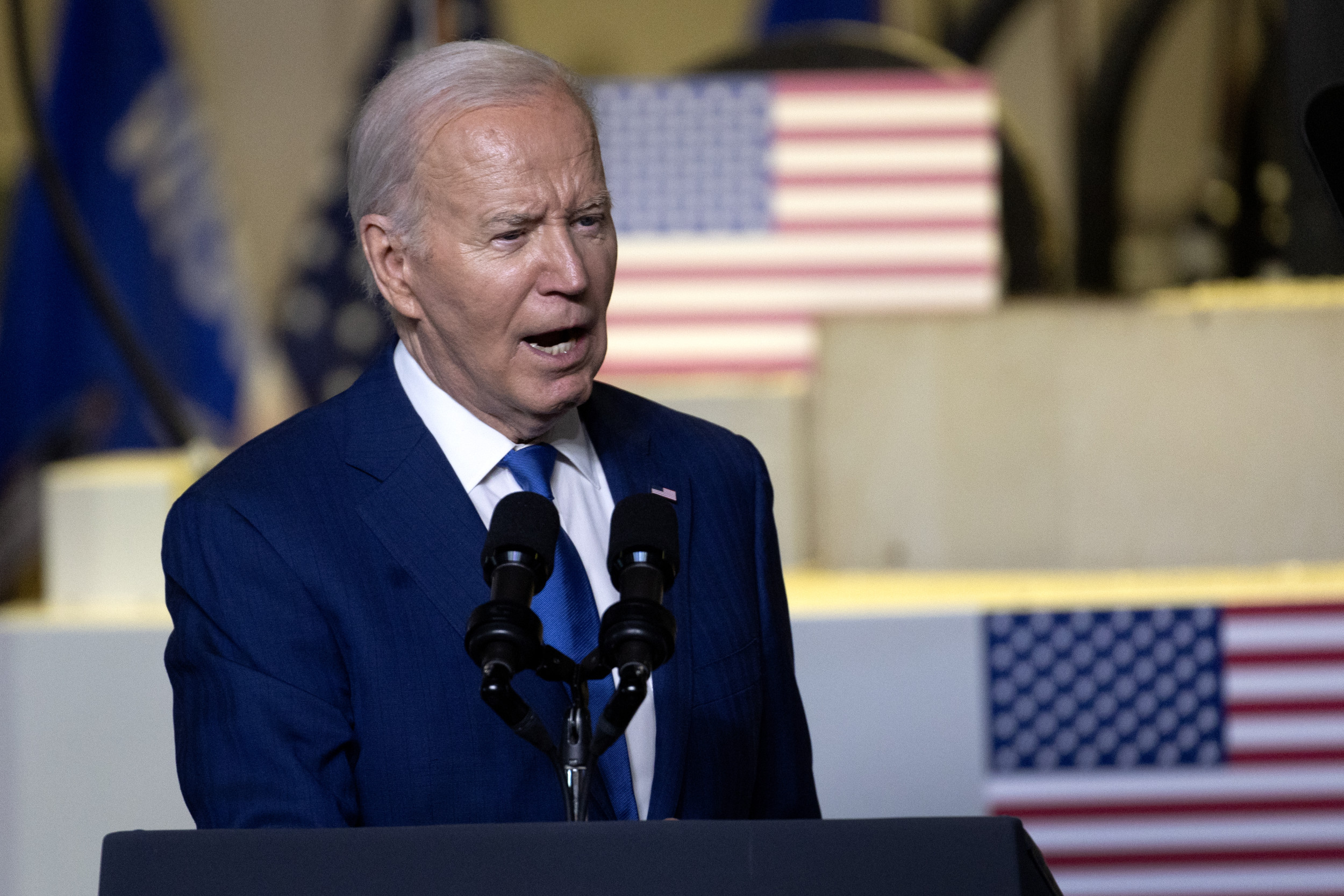

Kim, however, doesn't appear all that interested in diving into another diplomatic process with Washington. The Biden administration has tried to contact the North Koreans multiple times in the hope diplomacy could be resurrected (the U.S. and North Korea haven't had direct meetings since October 2019). Overtures in February 2021 went unanswered—and if the words of North Korean officials are an accurate barometer of the future, opportunities for a sit-down between these two historical enemies aren't particularly bright.

For the Biden administration, the options on North Korea are limited. Thus far, the White House has taken a dual-track approach, stressing openness to diplomacy without preconditions while retaining (and at times, increasing) the amount of financial pressure on the North Korean economy. Through it all, the U.S. State Department continues to remind anyone who will listen that North Korea's full, complete, irreversible denuclearization is official U.S. policy.

The only problem? The strategy isn't working. The North isn't begging the U.S. for sanctions relief. If anything, the country is largely adopting a business-as-usual mentality, implementing its own weapons development plans in order to master a dynamic, durable and effective deterrent. The aim? To send a message to Washington and its allies in northeast Asia that any forceful intervention would entail extreme costs.

The U.S., therefore, has a choice to make.

The first course of action is to continue the status-quo ante, which places a premium on denuclearization as a viable policy. This is arguably the path of least resistance. But it also happens to be a path riddled with the carcasses of previous policy failures. North Korea is one of the most heavily sanctioned countries in the world, yet it's also a master at skirting those sanctions. The possibility of Washington passing additional economic restrictions through the U.N. Security Council is dim, with China and Russia using North Korea as a wedge issue to frustrate U.S. policy. And even if China could be convinced to get onboard with tougher sanctions (highly dubious given the intensified U.S.-China rivalry), the fact remains that Beijing will only do so much on this front. China's top priority with respect to the North isn't denuclearization but stability. China could theoretically bankrupt Pyongyang (China accounts for 90 percent of North Korea's total trade), yet doing so would create a humanitarian catastrophe next door and a massive refugee crisis on China's border.

The second course of action for the U.S. is to lower its sights to more realistic and achievable objectives. But for this to happen, U.S. policymakers need to swallow the harsh reality: Denuclearization is a pipe dream. No country in the history of the nuclear age has developed dozens of nuclear warheads, only to trade them away for economic and political concessions. North Korea is unlikely to be the first. For the Kim dynasty, the security associated with being a nuclear weapons state is more valuable than a thriving economy or full acceptance in the international community.

To put a fine point on it: The U.S. needs to stop deluding itself. If it wants North Korea to stop sending ballistic and cruise missiles into the sky, it will need to attach its calls for diplomacy with a concrete package and spell out clearly what it's willing to offer Pyongyang in return for nuclear and missile concessions. In other words, if it wants a negotiation, Washington needs to actually negotiate.

North Korea won't give up its nuclear and missile programs in total, that much is clear. But North Korea may be open to a discussion about capping and rolling back these programs for tangible economic relief and a more productive relationship with the U.S. Pyongyang has never explicitly ruled this formula out. Kim made such a proposal to the U.S. during the Trump administration, linking the destruction of the large Yongbyon nuclear production facility with a lifting of most U.S. and U.N. economic sanctions. Those talks, of course, broke down; President Donald Trump thought the North Koreans were demanding too much in exchange for giving away too little. Pyongyang has been full steam ahead ever since, testing a variety of missiles from a variety of launchers, including submarines and trains.

To the outside observer, watching satellites picking up images of large, menacing-looking North Korean projectiles can be a bit nerve-wracking. In truth, the U.S. will be fine regardless. Washington, possessing the most sophisticated, lethal military on the face of the planet, is quite experienced in deterrence. No rational adversary believes the U.S. would flinch from employing those capabilities if direct U.S. interests were attacked. Kim Jong Un is one of those rational adversaries, someone who grasps the baseline notion that actually using the North's weapons against the U.S. or its treaty allies would produce the kind of regime-ending retaliation he wishes to avoid.

The overall point, though, is this: If the U.S. wants North Korea to cease and desist from missile tests, it needs to have the fortitude to negotiate a cap on them. Otherwise, we can expect more launches in the future.

Daniel R. DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a foreign affairs columnist at Newsweek.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.