Prospects for a framework agreement between the Palestinians and the Israelis were brightening as the spring approached. During the President's trip in January, we'd both been impressed by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert's desire to get a deal. After the Annapolis Conference, he'd placed Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni in charge of the Israeli side of the negotiations, and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas had tapped Abu Alaa. There was something of an asymmetry since the Palestinian team was experienced, having negotiated the issues for more than fifteen years. Like the back of their hands, the team members knew the ins and outs of the maps, the nuances of the phrases, and the history of the conflict. Tzipi admitted that she didn't know the issues as well but she came up to speed very quickly. I traveled to the region even more frequently, holding meetings with each side separately and several times jointly. The progress was slow but steady. At one point, to better understand the Palestinian concerns about the Israeli settlement of Ariel, Tzipi even suggested a joint field trip to see it. I was convinced that the parties were trying very hard.

In March I made two trips to the region, and I made another in April. With those trips, I had fallen into a pattern, meeting with the Arabs through the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] and covering everything from Iraq to Afghanistan to Annapolis. I'd then go on to meet with the Palestinians and the Israelis, starting in Jerusalem with dinner at Olmert's house. At first, I'd take Elliott Abrams, who traveled with me from the White House, David Welch, and the ambassador. Shalom Turgeman and Yoram Turbowitz, Olmert's close advisors, usually accompanied the prime minister. After dinner, Olmert and I would go into his study. He'd smoke a cigar, I'd drink tea, and we would go deeper into the issues that had come up at dinner.

But when I arrived in Jerusalem in May, I got word that Olmert wanted me to come to dinner alone. I was a little surprised, but we'd met one-on-one at least once before. When I got to the residence of the prime minister, he didn't waste much time on pleasantries.

"Tzipi is a hard worker, and she has my complete confidence," he began. Why is he telling me that? I wondered. Then he made himself clear. "The problem is that the process with Abu Alaa isn't going to get it done in time. Israel needs to get an agreement with the Palestinians before you leave office," he said. He continued without waiting for me to respond. "I want to do it directly with Abu Mazen," he said, referring to Mahmoud Abbas by his nom de guerre. "You are going to see him tomorrow. Tell him that I want to appoint one person. I have someone in mind. He is a retired judge that I trust. I want Abu Mazen to appoint a trusted agent too. We can write down the agreement in a few pages and then give it to the negotiators to finalize," he said. I started to ask about the relationship between what he was proposing and what Tzipi was doing. I felt kind of awkward because it was pretty clear he hadn't told her what he was telling me. But as I opened my mouth, Olmert started talking again.

"I know what he needs. He needs something on refugees and on Jerusalem. I'll give him enough land, maybe something like 94 percent with swaps. I have an idea about Jerusalem. There will be two capitals, one for us in West Jerusalem and one for the Palestinians in East Jerusalem. The mayor of the joint city council will be selected by population percentage. That means an Israeli mayor, so the deputy should be a Palestinian. We will continue to provide security for the Holy sites because we can assure access to them." That's probably a nonstarter, I thought. But concentrate, concentrate. This is unbelievable. He continued, "I'll accept some Palestinians into Israel, maybe five thousand. I don't want it to be called family reunification because they have too many cousins; we won't be able to control it. I've been thinking about how to administer the Old City. There should be a committee of people—not officials but wise people—from Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the Palestinians, the United States, and Israel. They will oversee the city but not in a political role." Am I really hearing this? I wondered. Is the Israeli prime minister saying that he'll divide Jerusalem and put an international body in charge of the Holy sites? Concentrate. Write this down. No, don't write it down. What if it leaks? It can't leak; it's just the two of us.

Olmert was on a roll. "I will need your help on security. The IDF has a list of demands—some of them probably are okay, but the Palestinians won't accept all of them. I need the United States to work this out to the satisfaction of the military. Barak will work with you. I can sell this deal, but not if the IDF says it will undermine Israel's security. That's the one thing no prime minister can survive. And one other thing, I need to know that you won't surprise me by offering other ideas before we've had a chance to talk about them. I'm taking an enormous risk here, and I can't be blindsided by the United States." Olmert had been leaning forward; neither of us had touched our dinner, and when the server had come in, he'd shooed her away. Now he sat back in his chair, exhausted by the recitation of the extraordinary details of the deal as he saw it.

"Prime Minister, this is remarkable, and I will try to help. I will talk to Abu Mazen tomorrow," I promised. "Be careful where you speak to him because people may be listening," he said.

After dinner, I hurried back to the hotel and related the details to David and Elliott only—minus the proposal on an international committee to oversee the Holy sites. I trusted my advisors, but a slip of the tongue on that one would have been devastating to Olmert. "You must not tell anyone," I said sternly, knowing that they wouldn't. Then I called Steve Hadley and told him that I had some extraordinary news but didn't feel comfortable—even on a secure phone—repeating what I'd heard from Olmert. After all, I was in an Israeli hotel; one never knew who might be listening. "Tell the President he was right about Olmert. He wants a deal. And frankly, he might die trying to get one," I said, recalling that Yitzhak Rabin had been killed for offering far less. I hung up the phone and looked out my window at the Holy City. Maybe, just maybe, we could get this done.

The next day I went to see Abbas and asked to see him in the little dining room adjacent to his office. I sketched out the details of Olmert's proposal and told him how the prime minister wanted to proceed. Abbas started negotiating immediately. "I can't tell four million Palestinians that only five thousand of them can go home," he said.

I demurred, saying that he should make his concerns known to the prime minister. "Are you ready to talk with him alone?" I asked. Abbas said that he would but could not appoint a trusted agent—he wanted to do this himself. I sensed that the internal politics of the Fatah party were such that he could not sidestep Abu Alaa, a power in his own right and sometimes a rival within the party. This is going to be a problem, I realized. But just get them together, and see what happens—one step at a time.

I called the prime minister before I left and said that Abbas was ready to talk but wanted to do it himself. The prime minister said that he'd arrange a meeting. "What language will you use?" I asked.

"English," Olmert replied.

"Remember that you speak it better than he does. He'll be at a disadvantage," I countered.

"It isn't my intention to put him at a disadvantage," he replied. I think he really means that, I thought. "I'll be in touch, Prime Minister," I said. "And I'll tell the President about our discussions."

Olmert ended by saying, "Remind him of our first meeting when I said that I wanted a deal."

In the waning months of our time in Washington, we tried one last time to secure a two-state solution. The Olmert proposal haunted the President and me. In September the prime minister had given Abbas a map outlining the territory of a Palestinian state. Israel would annex 6.3 percent of the West Bank. (Olmert gave Abbas cause to believe that he was willing to reduce that number to 5.8 percent.) All of the other elements were still on the table, including the division of Jerusalem. Olmert had insisted that Abbas sign then and there. When the Palestinian had demurred, wanting to consult his experts before signing, Olmert refused to give him the map. The Israeli leader told me that he and Abbas had agreed to convene their experts the next day. Apparently that meeting never took place. But I knew what had been proposed, and I asked Jonathan Schwartz, a State Department lawyer with many years of experience in the issue, to construct an approximation of the territorial compromise. I wanted to preserve the Olmert offer.

I talked to the President and asked whether he would be willing to receive Olmert and Abbas one last time. What if I could get the two of them to come and accept the parameters of the proposal? We knew it was a long shot. Olmert had announced in the summer that he would step down as prime minister. Israel would hold elections in the first part of the next year. He was a lame duck, and so was the President.

Still, I worried that there might never be another chance like this one. Tzipi Livni urged me (and, I believe, Abbas) not to enshrine the Olmert proposal. "He has no standing in Israel," she said. That was probably true, but to have an Israeli prime minister on record offering those remarkable elements and a Palestinian president accepting them would have pushed the peace process to a new level. Abbas refused.

We had one last chance. The two leaders came separately in November and December to say good-bye. The President took Abbas into the Oval Office alone and appealed to him to reconsider. The Palestinian stood firm, and the idea died.

Now, as I write in 2011, the process seems to have gone backward.

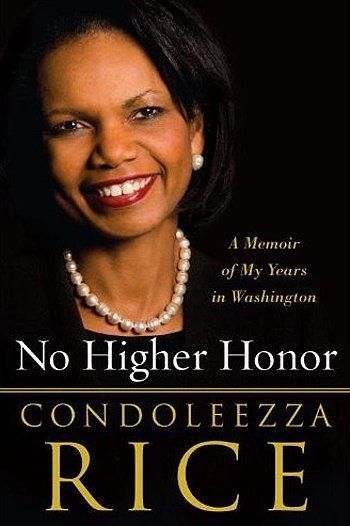

Excerpted from the forthcoming No Higher Honor by Condoleezza Rice. Copyright © 2011 by Condoleezza Rice. Printed with permission by Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All Rights reserved.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.