Washington's leaders are in the hot seat as protesters over the killing of George Floyd by a Minnesota cop demand criminal justice and police reform.

But some members of Congress question the political viability of accomplishing reform anytime soon—given the Legislative Branch's track record on the issue—while others question whether they should have any role at all.

"Is there a right legislative response? I don't know. And I have to admit that as a leader, I don't know," said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska). "And that vulnerability, to me, is very unsettling. People are looking—Alaskans are looking to me. 'Help.'"

The furor and unrest across the country after Floyd's death is pressuring lawmakers to scramble to respond to a crisis within a crisis, considering Congress is expected to begin negotiating another pandemic relief package in the coming weeks.

Sarah Binder, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who specializes in Congress and legislative politics, is skeptical that lawmakers are up to the task of swiftly tackling such historic racial inequalities for a multitude of reasons: partisanship, ideology and special interests are chief among them amid an election year. She said lawmakers should eye proposals that would curtail the transfer of military equipment to local police forces, change qualified immunity for officers, create a national registry to track excessive uses of force and prohibit certain police practices.

But there is some glimmer of hope, Binder said.

"We're used to seeing a Congress that in face of pressure has a tough time because the parties often disagree with each other whether something is a problem," she told Newsweek. But now, she said, "there seems to be bipartisan agreement on the nature of this issue."

Quick-fix police reform measures are flying around on Capitol Hill to address the systemic and pervasive problem of criminal injustice against minorities.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), for example, has called on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to have a police reform package on the floor by July 4—an ambitious timeline for Congress to tackle anything, much less such a complex topic.

"I thought he would want to deal with COVID-19. Senator Schumer can't make up his mind what he wants," said Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), a leadership member. "It's whatever the news of the day is."

Although it will likely be weeks or months—if ever—before concrete action takes place, Congress is already taking steps that could later lead to substantive proposals.

The House Judiciary Committee will hold a hearing next week on police brutality as House Democrats, led by Judiciary Chairman Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) and Congressional Black Caucus Chair Karen Bass (D-Calif.), begin to discuss potential legislative measures. Meanwhile, the Senate's judiciary panel is slated to hold a similar hearing later this month.

The public forums come alongside members' steps to chip at a decades-long problem.

For example, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) is looking to "stop the virus of racism" through new training, a national registry of officers who have been charged and convicted of police brutality, and stopping the use of military hardware by local police forces. Several of Blumenthal's Democratic colleagues, including Tim Kaine (Va.) and Brian Schatz (Hawaii), and at least one Republican—Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.)—said they will seek to bar the federal government from providing local agencies with military-grade weapons through an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act.

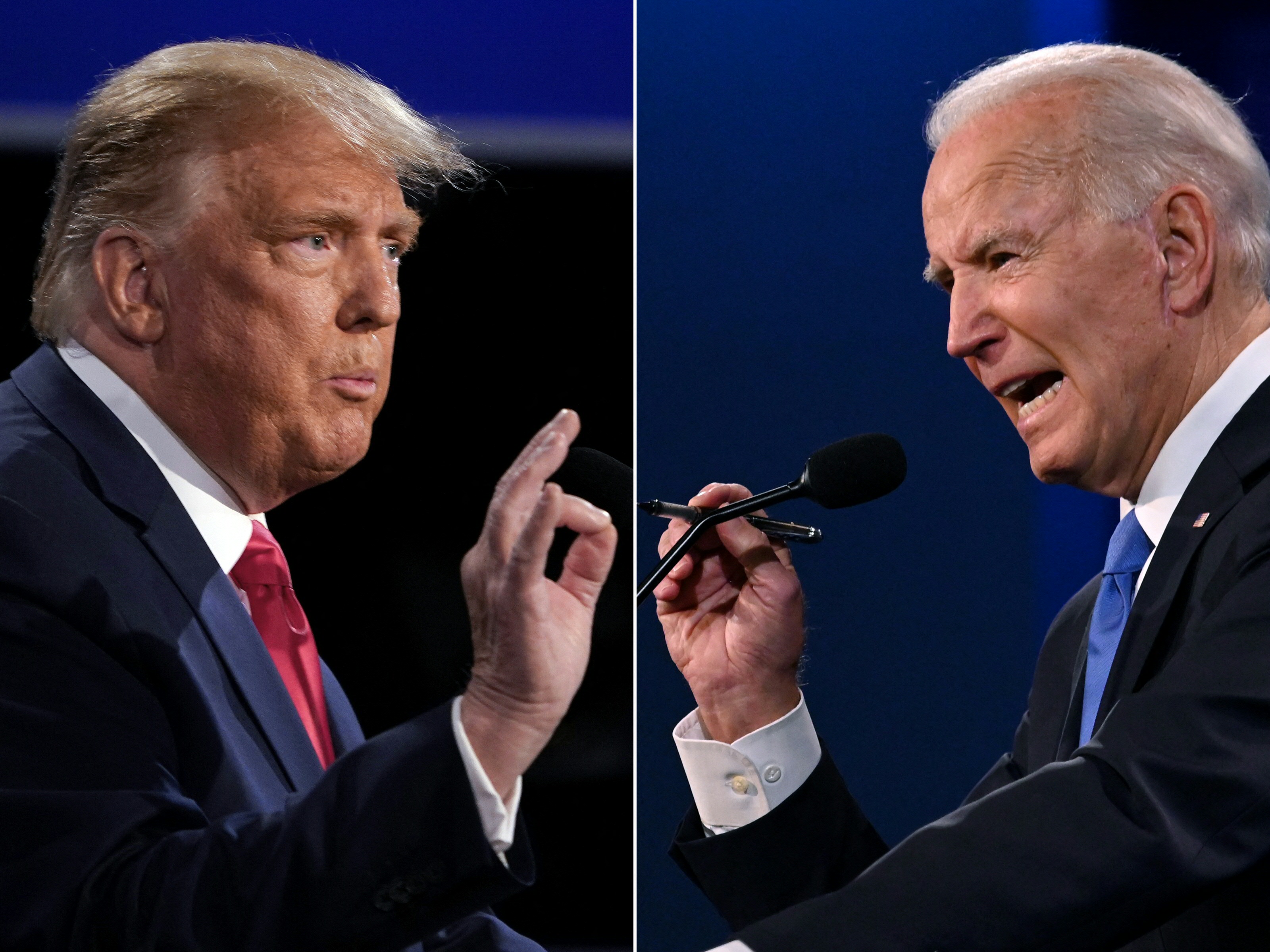

A proposal by Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (N.Y.), chairman of the Democratic Caucus, to ban police chokeholds following the killing of Eric Garner in 2014, who repeatedly told the white officer who had him in a chokehold "I can't breathe," went nowhere. But now, it has been revived by House Democrats and has received the endorsement of presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden.

Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, suggested more federal resources could be provided to improve community policing, best practices and "beef up some federal laws that protect people from having their rights abused." When it comes to qualified immunity or banning things like police chokeholds, Graham labeled those ideas as "tactical issues" that need to be examined.

"What is causing this? I want to hear from the cops. Are you afraid of young, black men? Because young, black men are definitely afraid of getting in a bad situation and police custody—justifiably so," Graham said. "When I see a cop behind me, I think, 'am I speeding? What have I done wrong?' I don't have any fear. But it's pretty prevalent in African American communities."

Despite these efforts, lawmakers face political reality. Not only is the current Congress hyperpartisan, but the ability for major criminal justice reform to pass any Congress does not have much place in American history. The most recent significant legislation in decades was the First Step Act in 2018. The law featured modest changes to mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug-related crimes that reduced sentences for some while helping others never return through increased focus on combating recidivism.

There were no specific discussions about police reform at a private Tuesday lunch with GOP senators, according to Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.). And while McConnell conceded to reporters afterward—"there is no question that there is residual racism in America," he said—the Kentucky Republican was noncommittal to legislation.

"It's certainly something that we need to take a look at," McConnell said. "We'll be talking to our colleagues about what—if anything—is appropriate for us to do in the wake of what's going on."

Senator James Inhofe (R-Okla.) said he "can't imagine" reform would come. If he did, he said, "I highly suspect it would be political."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ramsey Touchberry is a Washington Correspondent for Newsweek based in the nation's capital, where he regularly covers Congress.

Prior to ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.