Update | For the first time, scholars have found a copy of the original Greek manuscript describing what Jesus purportedly taught his brother James in secret.

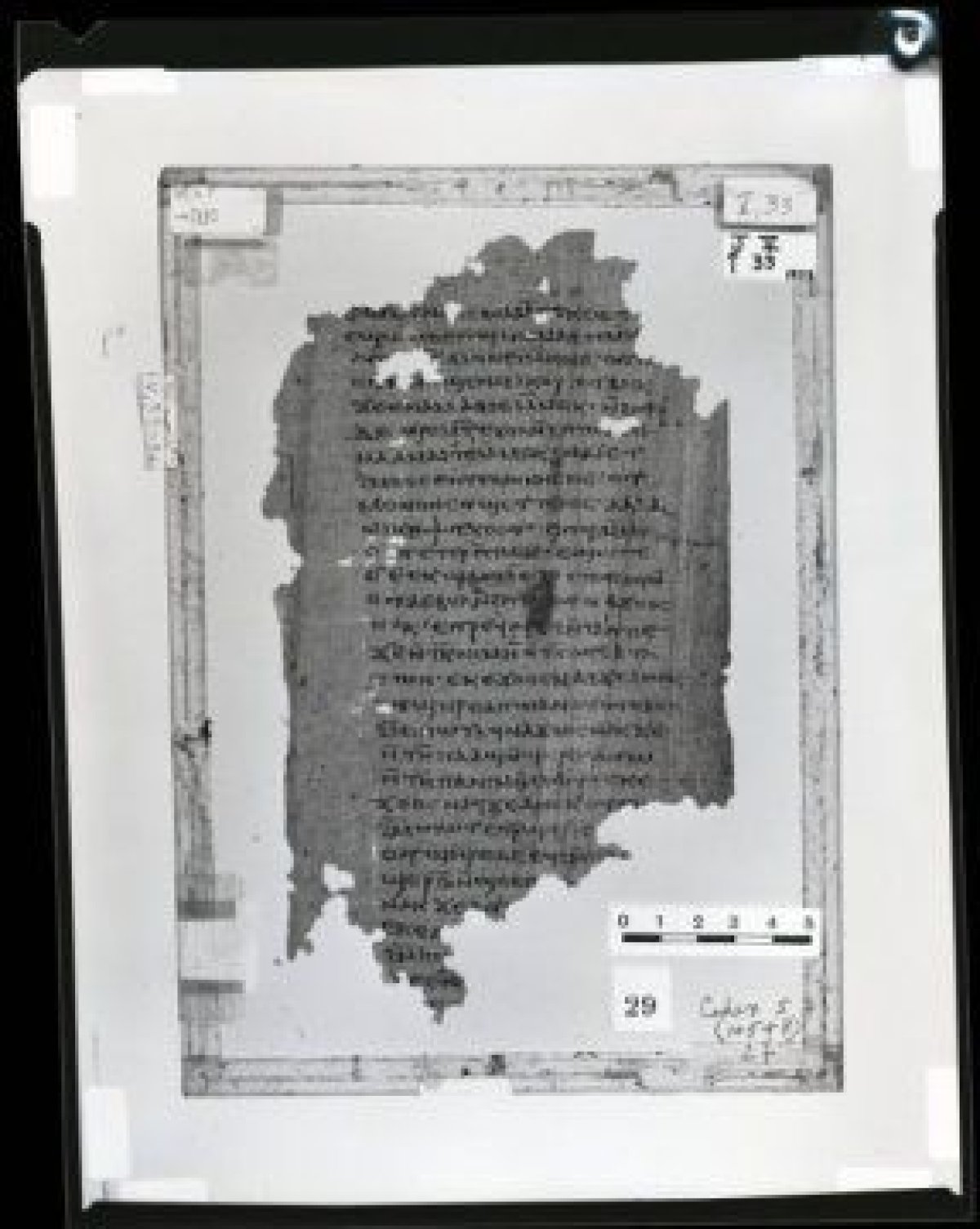

Biblical scholars at the University of Texas at Austin discovered the manuscript in the Nag Hammadi Library at Oxford University, where it may have been a tool teachers used to help students learn to read and write. According to a press release from The University of Texas at Austin, to find a copy of such a manuscript in Greek, the language in which it was originally written, is incredibly rare.

The Nag Hammadi Library is a collection of 13 Coptic Gnostic books, also called codices, that were found in Egypt more than 70 years ago. Only a small handful of works from the library have been recovered in their original Greek versions.

"This new discovery is significant in part because it demonstrates that Christians were still reading and studying extra-canonical writings long after Christian leaders deemed them heretical," Geoffrey Smith, an assistant professor of religious studies at The University of Texas at Austin and one of the two scholars who made the discovery, told Newsweek via email.

Smith and fellow religious scholar Brent Landau announced the discovery at the Society of Biblical Literature's Annual Meeting in Boston. The heretical Christian writings describe Jesus teaching his brother James, in secret, about future events, including James's own death. As Smith explained in the UT Austin press release, writings that added to or changed the existing New Testament in any way were forbidden. Orthodox Christianity teaches that such writings are fraudulently attributed to Jesus or other disciples.

"Jesus tells his brother James that though they are both going to die violently, death is not something to be feared," Landau, a lecturer at the UT Austin Department of Religious Studies, told Newsweek over email. "All James needs is to remember the passwords that his brother has taught him, so that he can escape from the clutches of the archons, a set of demonic beings guarding the material world."

Landau explained in a release that the scribe separated the majority of the text using "mid-dots," which broke words down into individual syllables. That was not a common practice at the time; the exception would be in educational contexts, which is why Smith and Landau believed the text was a teaching tool.

"To say that we were excited once we realized what we'd found is an understatement," Smith said in a release. "We never suspected that Greek fragments of the First Apocalypse of James survived from antiquity. But there they were, right in front of us."

As reported by CNN, in 2002 archaeologists discovered a 2,000-year-old "bone box" inscribed with Aramaic words that translated to "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." It was potentially the first physical evidence of Jesus's existence and sparked curiosity over who exactly this mysterious brother was. One theory, as professor of New Testament interpretation at Asbury Theological Seminary Ben Witherington III explained to CNN, was that Jesus and James were indeed full brothers (James was younger).

"The New Testament says nothing about Mary being a perpetual virgin; it says she virginally conceived Jesus, and it certainly implies that she went on to have more children after that, and his brothers and sisters are in fact his brothers and sisters," Witherington told CNN.

This story has been updated to include comments from Geoffrey Smith and Brent Landau to Newsweek and to clarify that other information and comments came from a press release from The University of Texas at Austin.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kastalia Medrano is a Manhattan-based journalist whose writing has appeared at outlets like Pacific Standard, VICE, National Geographic, the Paris Review Daily, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.