One of the most impressive and eclectic intellectual groups in America gathers in a sprawling former mansion nestled in the foothills above Santa Fe. Once the private residence of a former U.S. Secretary of War, the space now houses the Santa Fe Institute. Lunchtime conversations range from game theory to historical linguistics to Sophocles. Pulitzer Prize–winning authors, Nobel Laureates and MacArthur geniuses wander the halls, scrawling equations on the window panes with erasable markers. The novelist and philosopher Rebecca Goldstein calls it "everything I hoped academia would be as a graduate student." She adds, "It was pure bliss."

The Santa Fe Institute was founded in 1984 by a group of scientists frustrated with the narrow disciplinary confines of academia. They wanted to tackle big questions that spanned different fields, and they felt the only way these questions could be posed and solved was through the intermingling of scientists of all kinds: physicists, biologists, economists, anthropologists, and many others.

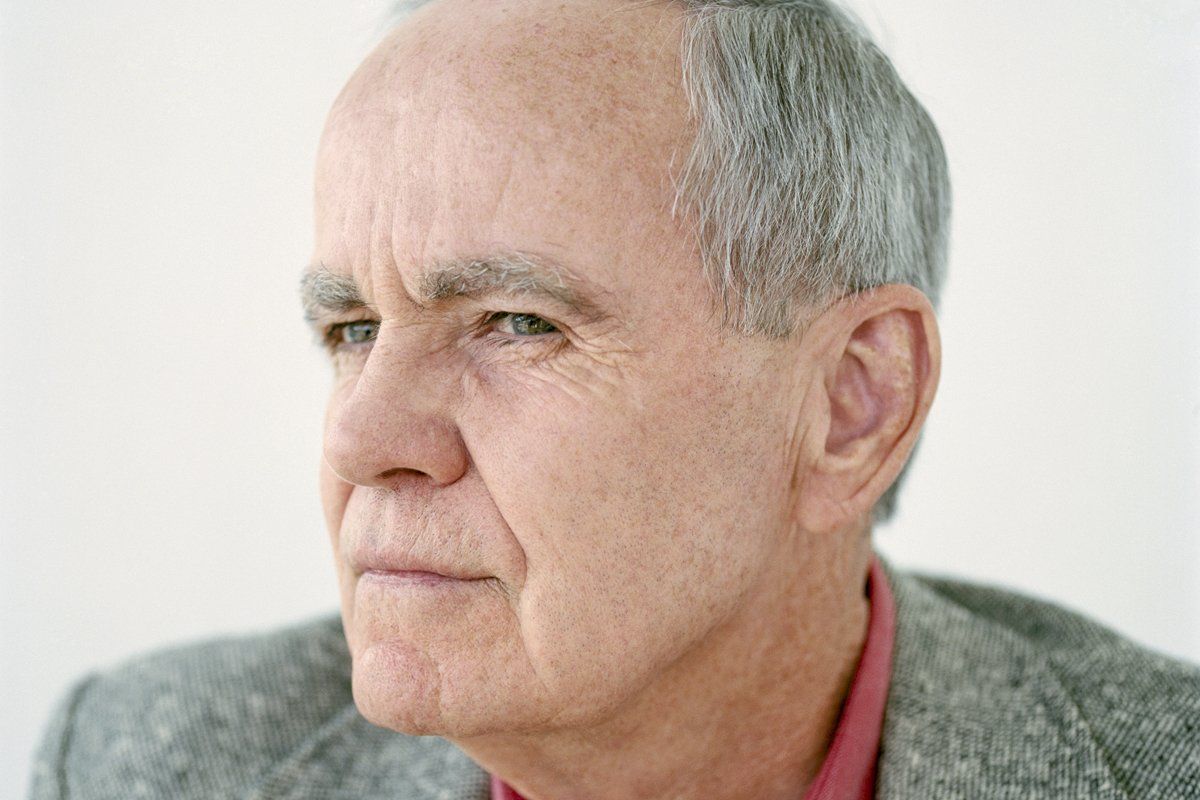

Almost three decades after its founding, the institute now has 12 resident faculty members whose interests range from the archaeology of the American Southwest to the physics of cities. Various educational programs and conferences supply fresh infusions of graduate students, post-docs, and professors from around the country. Over the last few years SFI has even extended the logic of collaboration further by establishing a regular fellowship to bring a novelist, playwright, philosopher, or other humanist to the institute. Though he's technically a member of the board of trustees, Cormac McCarthy has also become a vital part of the intellectual atmosphere.

If the Santa Fe Institute is a kind of modern-day Lyceum, then physicist Murray Gell-Mann is its Aristotle. A polymath with a profound depth and breadth of knowledge, Gell-Mann has been a presiding figure at SFI ever since he helped to found it. Now in his 80s, he still comes to the institute each day and engages visitors in energetic conversation at lunch.

A colleague once remarked that Gell-Mann didn't have any particular aptitude as a physicist, but was so generally brilliant that when he studied the subject he became a world-class physicist. In 1969 he received the Nobel Prize in physics for his contributions and discoveries concerning the classification of elementary particles and their interactions. He's also famous as the discoverer of a subatomic particle called the quark. A prodigious reader and student of many languages, Gell-Mann named the quark after a line from Joyce's Finnegan's Wake, "Three quarks for Muster Mark!/Sure he hasn't got much of a bark."

Gell-Mann met McCarthy at an event sponsored by the MacArthur Foundation in the 1980s and the two quickly developed a friendship based on a shared interest in math, physics, literature, and practically every other subject imaginable. McCarthy began coming to the institute in the 1990s and has been a regular fixture there for the past decade. "I've written a few books here," he told me.

McCarthy's influence permeates SFI in various ways. The sound of his old typewriter keys clacking is sometimes audible in the common areas, his questions at panels and meetings often inspire the scientists, and his remodeling work has imbued the space with a subtle but pervasive aesthetic. Throughout the institute he has hung heavy gilt mirrors and installed dark wooden cabinets and furniture that looks like it might have come from a hacienda in his Border Trilogy; he has commissioned a painting of Newton by the Texas artist Alberto Escamillo that hangs in the main conference room (once a ballroom); and he's refinished the front desk with pine, cedar siding, and cherry wood. His current project is a renovation of the second conference room. While I was visiting the institute, McCarthy stopped to chat with a contractor about the cedar wainscoting that will panel the base of the room.

When he's immersed in writing, McCarthy's impact on the institute is more acoustic than visual. "I had an office in C-pod one summer, and the kids heard all this noise," McCarthy said, referring to a new wing of the institute where post-docs and graduate students gather in the summers. "They kept peering in the door, and one finally came up and knocked. I said, 'Yes?' and he looked at the typewriter and said, 'What is that?'"

McCarthy may strike the younger generation as a Luddite in his use of a typewriter, but various scientists at SFI praise his ability to contribute to conversations on the latest trends in science. "Cormac is scary," said physicist Luis Bettencourt, who collaborates with physicist Geoffrey West on work that studies cities as physical systems subject to the same scaling laws as other natural systems like cells, ecosystems, and organisms. "He just asks really good questions," he added. Neuroscientist Chris Wood said that McCarthy's knowledge of math and physics, and in particular the histories of those fields, exceeds that of many professional physicists and mathematicians.

At first glance, McCarthy's presence at the institute doesn't seem to support SFI's founding premise: that intellectual vitality arises from people interacting across a wide range of disciplines. Though he writes novels at the institute, in his conversations with scientists he doesn't act as an ambassador for the novel, explaining its dialect and customs to foreigners. On the contrary, he functions as an acutely curious and supremely competent amateur scientist. As we chatted, his novels seemed to strike him as almost an afterthought.

"I'm not here because I'm a novelist," McCarthy told me with a smile. "I just managed to sneak in. I haven't read a novel in years." Though the scientists at SFI are quick to offer a host of reasons why humanists are valuable, McCarthy chuckled when I mentioned "orthogonality," the institute's term for the value of bringing together people with different backgrounds. "I don't know. It's the newest buzzword, it just means right angles. But I'm here because I like science, and this is a fun place to spend time. There's good craic." (Fans of his fiction know that any type of encounter with McCarthy tends to be vocabulary-expanding, and a chat at SFI is no exception: craic is a Gaelic word that means lively chat or conversation.)

The other novelist to spend extended time at SFI was Rebecca Goldstein, who spent four months at the institute as Miller Fellow in 2011. Like McCarthy, she has a keen interest in the history of science, and began writing novels after a career in analytic philosophy. While she was at the institute she gave a talk entitled "Why Einstein Wrote a (Bad) Love Poem to Spinoza." Goldstein spent most of her time at SFI falling into conversations about physics, evolution, the existence of free will, and similar topics. Novels or literature rarely came up.

Yet while Goldstein and McCarthy aren't consciously trying to analyze topics as novelists, their perspective sometimes supplies a way of thinking that's unusual among scientists. Bettencourt gave an example to describe the benefit of interaction with a novelist. "I was just talking with Cormac on crime in Mexico. It's relatively well measured, but the motives are fluid and complicated. We were talking about organized crime, which involves many factors. You have to understand demographics, corruption, the police, the tolerance of people for violence, and to some extent part of the challenge is knowing the dirt, the visceral, the unquantifiable and messy aspects. Novelists tend to have a different view than physicists, who are always trying to abstract things away." He continues, "The design here is to have an intellectually interesting place. And the payoff often doesn't come immediately. But it's impossible to do what we do without an environment so rich and diverse and haphazard."

The value of these types of interactions was precisely what motivated Geoffrey West to convince board member Bill Miller to fund a fellowship that would bring someone with orthogonal interests to work at the institute for an extended period. The philosopher Daniel Dennet was a Miller fellow, as were Goldstein and playwright Sam Shepard. "I don't consider it frivolous," West said of the presence of humanists. "They generate lots of discussion, ask interesting questions, and help us remain open to new ideas and speculations. It's impossible to quantify the effect of that, but it's an essential part of the fabric."

From a certain perspective, the opposition between humanists and scientists seems superficial. Authors like George Eliot and Charles Dickens read or were influenced by Darwin, and Darwin was a great lover of novels. He wrote in his autobiography that novels "have been for years a wonderful relief and pleasure to me, and I often bless all novelists." As Gell-Mann remarked at lunch one day, "Novels are part of civilization, and thus interesting." Our era of hyper-specialized subfields and mutually unintelligible vocabularies makes it easy to forget that borders between disciplines were once crossed more frequently.

McCarthy also noted that there are uniting features between science and literature. Both, for instance, share an aesthetic dimension. "There's an aesthetic to science. Some theories are just elegant; Maxwell's equations are aesthetically pleasing." When I mentioned a TED talk on physics in which Gell-Mann suggested that more beautiful theories are more likely to be true, McCarthy chuckled and offered a counter-example. "Dirac didn't think Feynman's theories were right based on their lack of aesthetic quality. He thought they were too complicated and ugly, but QED (quantum electrodynamics) was one of the major theories of 20th-century physics."

I asked whether something analogous happened in fiction: was a beautiful sentence more likely to be true in some way? McCarthy laughed. "That's tough. It's hard to define beauty, though there've been some strange attempts. We know it involves harmony, repetition, symmetry. These things speak to us and have for a long time."

"I'm not here because I'm a novelist," McCarthy told me with a smile. "I just managed to sneak in. I haven't read a novel in years."

In addition to aesthetics, McCarthy noted a deeper link between great science and great writing. "Both involve curiosity, taking risks, thinking in an adventurous manner, and being willing to say something 9/10ths of people will say is wrong." Profound insights in both domains also tend arise from a source beyond the limits of analytic reason. "Major insights in science come from the subconscious, from staring at your shoes. They're not just analytical." To explain why he doesn't like to analyze the sources of fiction too closely, McCarthy told a story. "There was a guy who was a great wing shot on a quail hunt in Georgia. He killed everything he saw, he dropped 'em all morning. One of the other guys said, 'You're the best wing shot I've ever seen.' At lunch the guy asked him, 'Do you shoot with one eye open or both?' He paused and thought about it. Finally he said, 'I don't know.'"

Playwright and actor Shepard came to the institute as a Miller fellow in 2011 and liked it so much that he bought a house in Santa Fe. Just before lunch one day, he walked out of a session that was part of a three-day conference on the co-evolution of human institutions and behavior. "I couldn't make heads or tails of it," he said. "It was on wealth distribution and fairness, and you go around and around in the same circles of reasoning, and ultimately who cares?" He filled a plate with pizza and salad, and sat down beside Gell-Mann. "It's important because of implications for the environment," Gell-Mann said. "As long as there's a huge contrast in wealth levels, we spend less on the environment."

Rebecca Saxe, a neuropsychologist at MIT, sat down next to Shepard and the two began discussing how the media often creates a misleading impression of scientists and artists. "The point of science journalism is an answer. But science is fundamentally human in that it involves not understanding things. We actually spend a lot of time in pursuit of the questions," she said. Just as science journalism tends to emphasize only results, interviews with authors often seek a simplistic summation of an entire work. "I can never answer the question 'What's it about?'" Shepard said. "Some people approach artists as if they have a secret. And if only they'd give it up then we could stop thinking about them."

Shepard still comes in to write at the institute most days, and he finds that he's at least twice as productive at SFI as he is anywhere else. He's currently working on a play that will open at New York's Signature Theatre in September.

He enjoys his increased productivity at SFI, but he also loves the conversation. As we were finishing lunch, Shepard tried to articulate what exactly makes SFI such a stimulating place. "Just the environment of people creates a certain electricity. I've never had a keen interest in science, more the people in it and around it. But part of the interest here is not knowing where the borders are. There's a story about Brendan Behan, an Irish playwright and drunk, who was traveling to Northern Ireland when he was stopped by the English. He'd had a few whiskeys and he crawled under the car. The English guy asked, 'What are you doing?' He said, 'I'm looking for the border.'"

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.