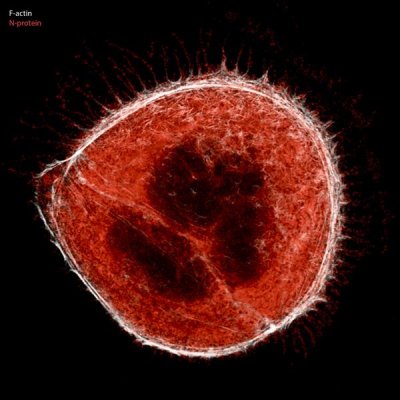

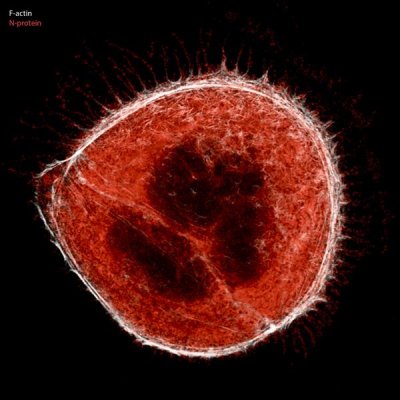

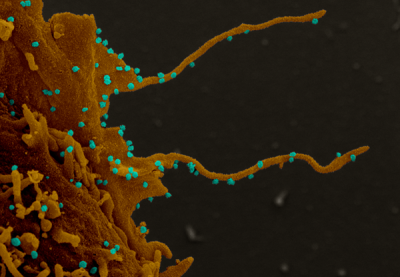

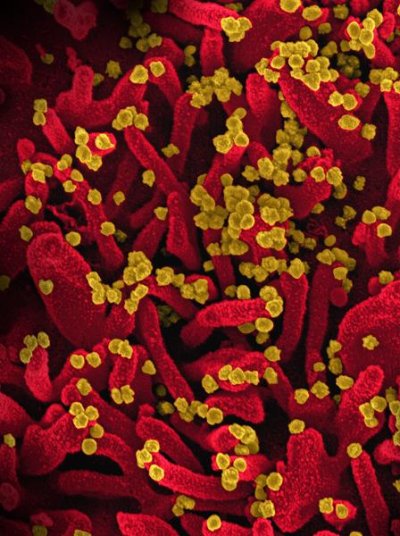

Microscopic images released by scientists show how the coronavirus which causes COVID-19 appears to make cells which it has invaded grow tentacle-like protrusions.

Researchers used special equipment to capture images of SARS-CoV-2, the name of the virus which causes COVID-19, after it infected monkey kidney cells in a lab.

Among their findings published in the journal Cell was that the virus seemed to trigger the growth of what are known as filopodia. These are thin protrusions rich in a protein which is important for actions including the movement and division of cells. They act as an antenna for cells to probe their surroundings.

In the images, they were dotted with new virus particles. The protrusions were "significantly longer and more branched than in uninfected cells," the authors wrote.

The team also spotted the "dramatic rewiring" of a process involved in how cells act, on both the host cells and viral proteins. These changes reflect how an enzyme called kinase is hijacked during infection, they said.

Co-author Pedro Beltrao of the European Bioinformatics Institute, said in a statement: "The virus prevents human cells from dividing, maintaining them at a particular point in the cell cycle. This provides the virus with a relatively stable and adequate environment to keep replicating."

Next, the team looked to see if existing drugs could target these alterations to treat SARS-CoV-2 infections. They found seven existing drugs which may help to combat the bug. Six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, there are currently no specific drugs to treat the disease, although existing drugs have been repurposed.

The work was limited, the researchers said, because they didn't use human cells to analyze the proteins. But they did use human lung cells in addition to the monkey cells to explore whether existing drugs affect SARS-CoV-2, the team said.

Kevan Shokat, Professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology at UCSF, said the team hopes to build on their work by looking at kinases in the hope of aiding the development of drugs to treat COVID-19.

Beltrao said: "Kinases possess certain structural features that make them good drug targets. Drugs have already been developed to target some of the kinases we identified, so we urge clinical researchers to test the antiviral effects of these drugs in their trials."

Co-author Nevan Krogan, director of the Quantitative Biosciences Institute at UCSF and Senior Investigator at Gladstone Institutes, said in a statement that seeing the "extensive branching of the filopodia" shows that understanding how viruses behave with a host can help to find potential ways to treat disease.

"Our data-driven approach for drug discovery has identified a new set of drugs that have great potential to fight COVID-19, either by themselves or in combination with other drugs, and we are excited to see if they will help end this pandemic," he said.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kashmira Gander is Deputy Science Editor at Newsweek. Her interests include health, gender, LGBTQIA+ issues, human rights, subcultures, music, and lifestyle. Her ... Read more