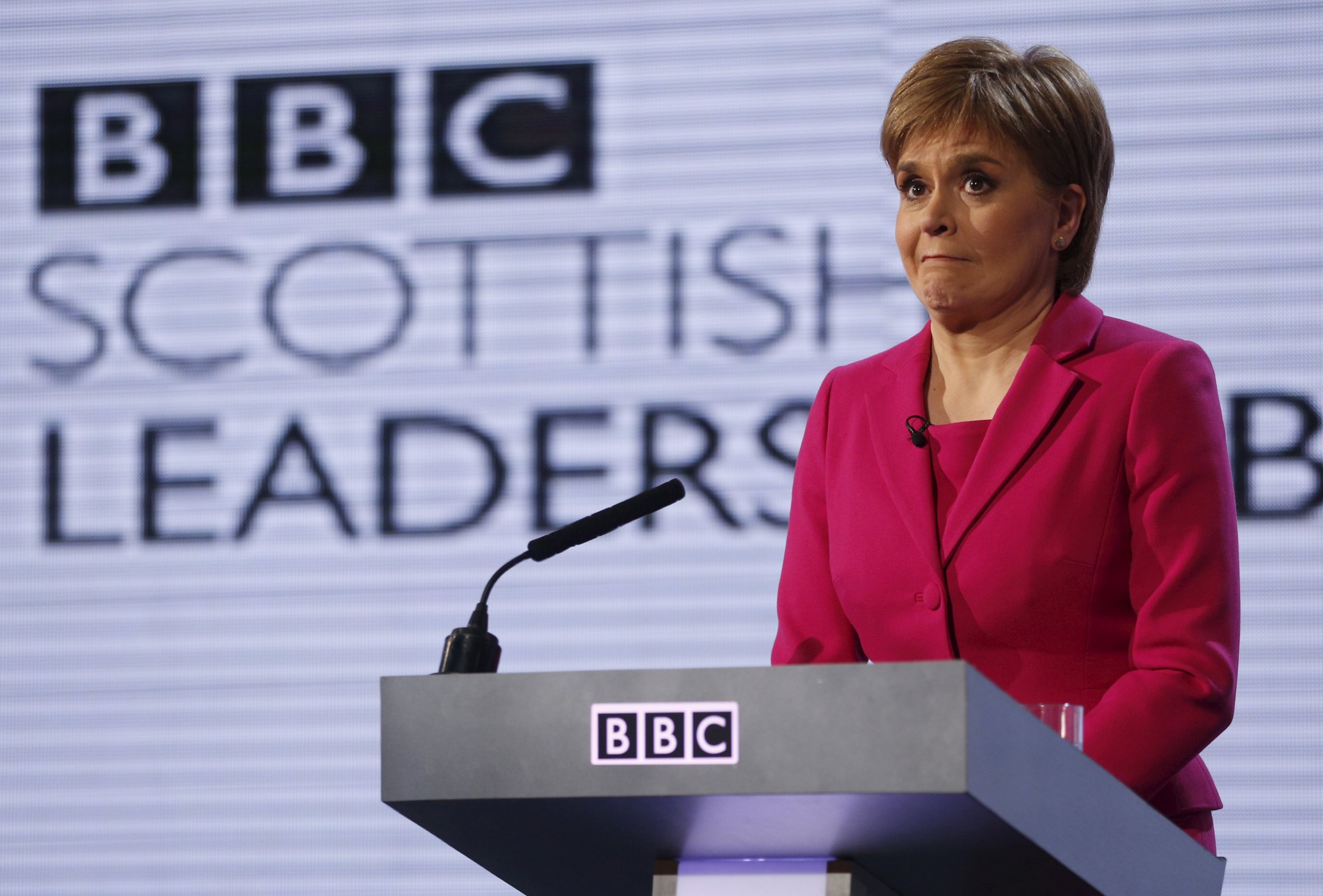

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland's First Minister, is reported to have declared over the weekend that the Scottish parliament might veto Brexit. Listen to her BBC interview, however, and you will notice that she does not use the word "veto." She is wise not to do so, because the Scottish Parliament does not have a formal veto. The process of extrication from the EU does, however, create major obstacles to the survival of the UK.

The crux of the matter is a clause in the Scotland Act of 1998—the law that established the Scottish parliament—saying that Holyrood (like the assemblies in Wales and Northern Ireland) cannot contravene EU law. In order for the UK to leave the EU cleanly, it will be necessary for legislation to be passed in Westminster removing that provision. But any amendment to the powers of the Scottish Parliament requires, by convention, the consent of the Scottish parliament. And Nicola Sturgeon has made it clear that such consent is unlikely.

Why does that not create a veto power? Two reasons. One is that, at least in theory, it would be possible to maintain the requirement for the Scottish parliament to act within EU law even after the UK has left the EU. This would create a messy situation, but it might be that this would be better than any of the alternatives. Indeed, some commentators have begun to float even more creative solutions to the current situation, such as the idea that Scotland and Northern Ireland could stay in the EU while England and Wales leave.

The other reason there is no veto power is that it is no more than a convention that Westminster will not act without the devolved institutions' consent and, furthermore, the convention provides only that "normally" it will not do so. Aspects of the convention were written into law earlier this year, but not the bit that is relevant here. So Westminster would not be violating any legal principle if it chose to ignore the absence of legislative consent.

That does not mean, however, that everything will be OK for the government in Westminster or for the future of the U.K. Acting against the convention on legislative consent might not violate any formal rules, but it would certainly violate the strong commitments that unionist politicians have made again and again—not least during the campaign for the 2014 Scottish independence referendum—that they would respect the authority of the devolved administrations. Scots already have considerable reason to feel that the assurances given two years ago—on respect for the will of the Scottish people in general and on continued membership of the EU in particular—have been betrayed. If it also turns out that a vote in the Scottish parliament on such a crucial matter can simply be disregarded, that will add further fuel to the fire.

Furthermore, the difficulty extends beyond Scotland. The Welsh first minister has said that, Welsh voters having supported Brexit, the Welsh Assembly should accept the result. But the Northern Ireland assembly is, like the Scottish Parliament, very unlikely to give its consent to legislative changes. The potential implications of Brexit for the future of the peace process and the future constitutional settlement in Northern Ireland remain far from clear.

All of this adds to the sense that the process of Brexit will put considerable strain on the future of the U.K. Indeed, the breakup of the U.K.—particularly, independence for Scotland—now looks much more likely than it did before. But it is not inevitable. While giving Scots renewed grounds for grievance, Brexit also makes the kind of independence that might be available less attractive than it would have been. A hard border with passport or customs controls between Scotland and England might be necessary, which many would find unpalatable. Furthermore, if Scotland becomes independent after the U.K. has left the EU, it might be expected to fulfil the usual requirements for new EU member states, such as joining the eurozone—which, again, could be a hard sell.

So, while the norms around legislative consent do not create a power of formal veto, they do certainly add extra rocks on the already rocky road to Brexit.

Alan Renwick is the deputy director of University College London's Constitution Unit.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.