A gene editing technique called zinc finger nucleases has been used for the first time in a human to treat a genetic disease, the AP reported Wednesday. A 44-year-old man named Brian Madeux was treated at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital Oakland for Hunter syndrome, a rare genetic disorder. The announcement comes days after a video showed exactly how another promising and landmark gene editing technique, CRISPR, works.

Gene editing is different than gene therapy; certainly, at least, the treatment Madeux had is working on a different level than anything seen before. Most gene therapies created for human use so far have stuck with using the body's natural mechanisms to transcribe a gene artificially added to cells using viruses. This time, though, doctors are trying to change Madeux's own DNA sequence.

Hunter syndrome, according to the National Institutes of Health, is caused because of a mutation in one particular gene called IDS. This gene codes for an enzyme that's necessary to break down a specific type of sugar molecules. Because of the mutation in the enzyme's gene, the sugar can't be broken down, it will build up in cells and cause problems. The condition can be treated with infusions of the enzyme that people with Hunter syndrome are missing; it's also possible to manage some of the other symptoms of the disease. However, it can't be cured.

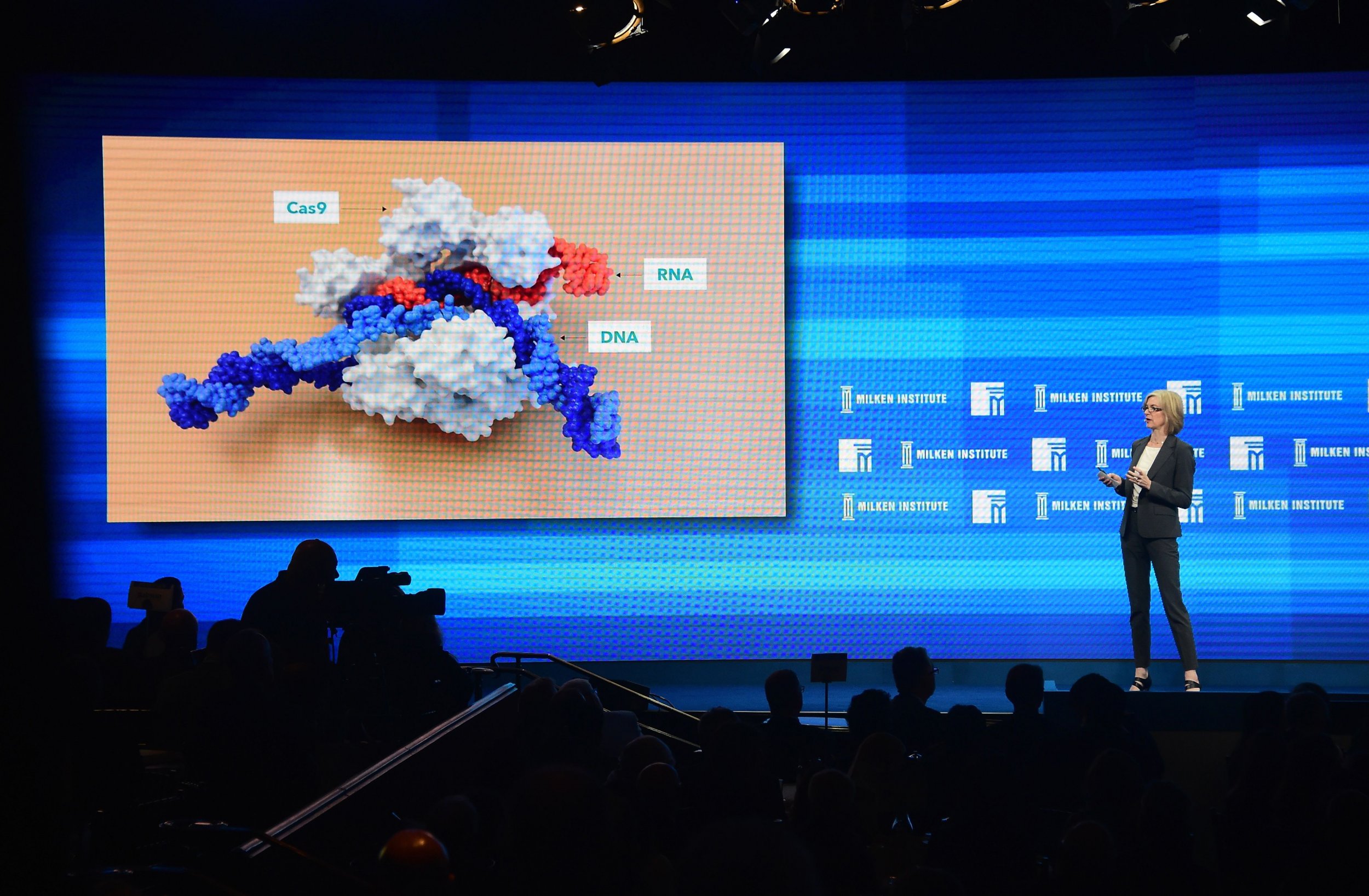

Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) are different than CRISPR, the gene editing technique that has dominated conversations in science and the media. Like CRISPR, ZFNs work by making a cut in DNA. However, the actual thing making the cut is different. (CRISPR is more accurately called CRISPR-Cas9, since Cas9 is the enzyme responsible for the cutting.)

You can actually see the enzymes making the cut in a new video. That video, the centerpiece of a new paper published in Nature Communications on Friday, was also shared on Twitter.

Single-molecule movie of DNA search and cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9. pic.twitter.com/3NQxmbvzJF

— hnisimasu (@hnisimasu) November 10, 2017

"I think the audible gasp at CRISPR 2017 meeting when [the researcher] played this video was one of largest reactions I've heard to new data being presented," Sam Sternberg wrote on Twitter. (Sternberg also spoke about the reaction to the data to The Atlantic's Sarah Zhang, who reported on the video.)

While it's good to know that CRISPR works exactly as scientists thought it does, gene editing in humans is still extraordinarily new and Madeux took very real risks. Based on tests done in animals, the treatment appears safe, the AP report noted, but inserting a mistake into the genome—a new mutation—is a possibility, as is editing the genes of cells that aren't meant to be edited. It's also not yet clear if the treatment worked at all; test results about the treatment are expected in early 2018.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kate Sheridan is a science writer. She's previously written for STAT, Hakai Magazine, the Montreal Gazette, and other digital and ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.