On March 19, 1979, C-SPAN began its first broadcast of the United States House of Representatives. The first on-camera speaker was then Representative Al Gore of Tennessee. It was a tremendous breakthrough in allowing citizens to see the House live and without editing or bias. The man who thought it through and made it possible is Brian Lamb.

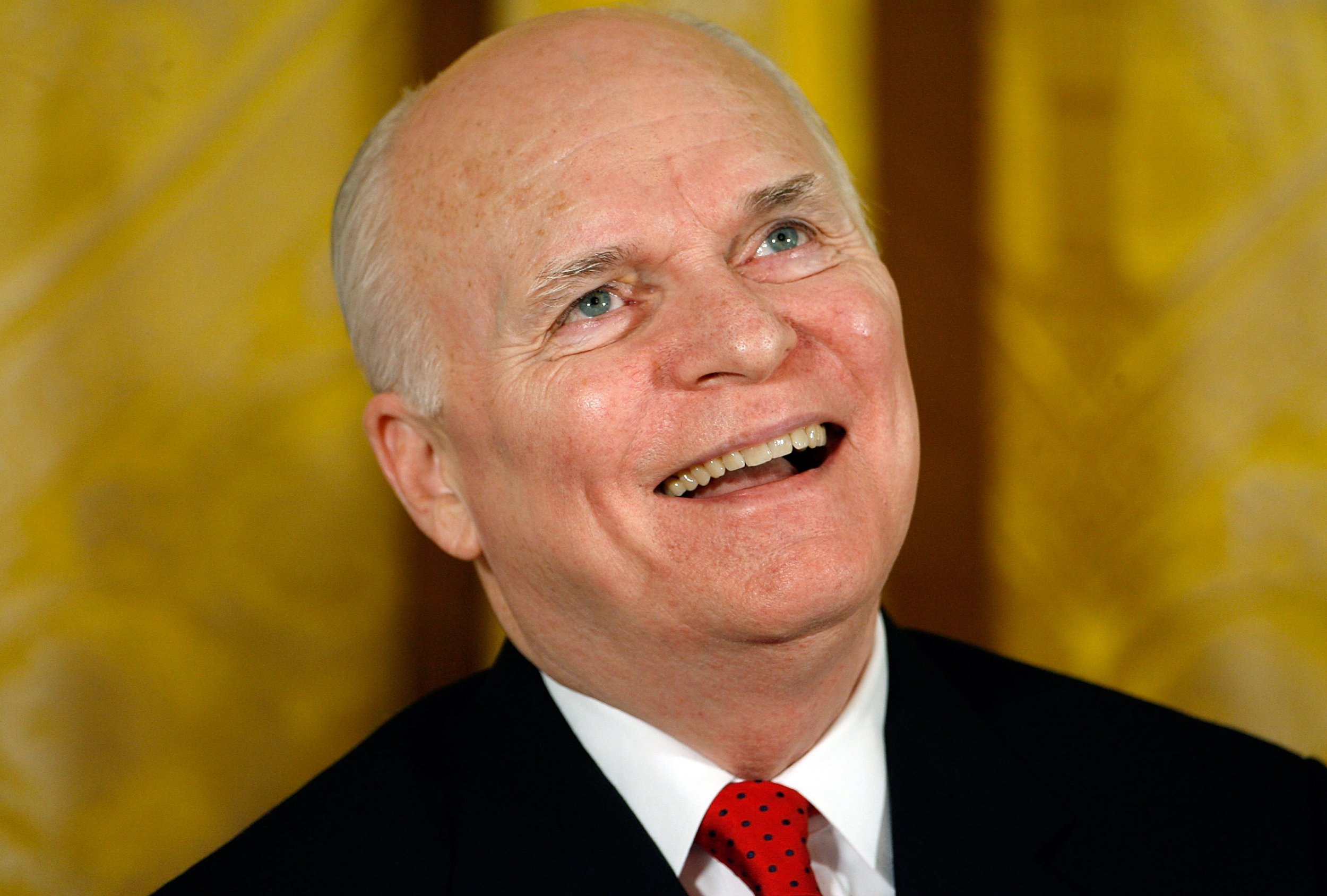

Brian Lamb, an Indiana born graduate of Purdue University, is one of the great social entrepreneurs of our lifetime. He envisioned a public service network connecting Americans to their Congress, convinced the cable industry it was affordable and created the series of three TV channels, a radio channel, and a wide variety of websites which constitute the modern C-SPAN system.

Today there are nearly 250,000 hours of archived material from C-SPAN, and the Brian Lamb School of Communication at Purdue University with its Center for C-SPAN Research is a national asset. The school continues Brian's commitment to helping the public understand government and politics by letting them experience it first-hand.

I have a particular affection for both C-SPAN and Brian Lamb.

I was a brand-new freshman (sworn in in January 1979 only two months earlier) when C-SPAN was born.

I had grown up with television. I did my first local TV shows when I was 17. I brought exotic animals from a local pet store to a children's show. I had studied Marshall McLuhan and had a sense of the power of television to change our world.

From the standpoint of the House of Representatives, I had been particularly impressed by David Halberstam's "The Powers that Be," which had captured Speaker Sam Rayburn's concerns that bringing media into the Congress would destroy the traditional power structure and give uncontrollable power to media savvy mavericks who could be powerful on the outside no matter what the old guard thought.

C-SPAN gave the minority Republicans the great opportunity to reach Americans without hostile editing. Furthermore, the House traditions of opening with one-minute speeches and allowing members at the end of the legislative session to give extended remarks for up to an hour gave new, unknown members opportunities to get their views out to their colleagues and to the public.

C-SPAN also gave conservatives an opportunity to express themselves directly to the American people without liberal editing or distorting.

We rapidly discovered that there was an audience that was eager to follow politics and government without editing or distortion. We had (and still have) a hard time convincing our colleagues that standing in an empty room talking to hundreds of thousands of people through C-SPAN was an effective tool for spreading ideas.

Members who would fly a thousand miles to talk to 250 people could not imagine that they could walk across the street to the House Chamber and address tens or hundreds of thousands of people at no cost.

Congressman Bob Walker and I became two of the earlier consistent users of C-SPAN.

There was a group of Republican women in Waterloo, Iowa who would watch us on C-SPAN and then, after our special orders, call each other and discuss what we had said. One of them went to Puerto Rico and saw Jack Kemp who was vacationing. She ran up to him and said, breathlessly, "Oh Mr. Kemp, do you serve in the House of Representatives?" Pleased at being recognized, Kemp who was the best-known House Republican and the national champion of tax cuts and supply-side economics, reassured her that he did, indeed serve in the House. She responded, "Oh Mr. Kemp, does that mean you know Bob Walker?"

Kemp came back to the House sharing with us the growing power of C-SPAN, and we promptly had t-shirts made up that said, "I Know Bob Walker."

Our first really big break on C-SPAN came through a fight with then-Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill. Walker and I, along with a number of other junior members, had been attacking the Democrats for supporting the Sandinista National Liberation Front (a communist group) in Nicaragua. In particular, we had been attacking a bill amendment which blocked the United States from spending money to overthrow the communists. It was called the Boland amendment after its author, Eddie Boland of Massachusetts, who was O'Neill's closest friend and roommate.

I was home in Georgia on a Monday afternoon when then-Republican whip Trent Lott tracked me down and said I had better get on the next plane back to Washington. He informed me that O'Neill had attacked me personally, and I had the right under House rules to take an hour of personal privilege and answer him.

When a junior member is attacked by the Speaker of the House, it creates a news opportunity too big to ignore.

The next day, I asked for an hour under the personal privilege rule and began defending what we had been doing to defeat communism and defend freedom in Nicaragua. O'Neil's staff tried to get him off the floor, but they couldn't. The more he listened to me the madder he got.

Finally, Speaker O'Neil jumped up and asked me to yield to him. Knowing that the nicer I was the madder he would get, I cheerfully gave him time. He then yelled in a loud voice:

"My personal opinion is this you deliberately stood in that well before an empty House and challenged these people, and you challenged their Americanism and that's the lowest thing that I've ever seen in my 32 years in Congress."

Billy Pitts, the Republican floor strategist, turned to Trent Lott and said intensely, "move to take the Speaker's words down." Lott jumped up and did so.

Taking the words down was a House procedure for dealing with someone who had clearly broken the rules. If it turned out Speaker O'Neill had indeed broken the rules by personally attacking me, he could be forced to be silent for the next 24 hours. No one had ever seen this applied to the Speaker of the House in modern times. In fact, it was almost unthinkable.

The entire House went quiet. The clerk had to finish writing down what Speaker O'Neill had said and then had to read it back for the record. All of this was on C-SPAN and members and staff members in their offices could see that something unusual was happening. The Capitol Hill press corps also began to be attracted to the unusual proceedings.

Making the situation even more difficult for Speaker O'Neill was the fact that his other roommate and close friend, Congressman Joe Moakley, was sitting in the Chair (O'Neill had to step down when I asked for an hour of personal privilege based on his attack on me). Here was poor Joe Moakley, who was a wonderful member—and virtually everyone's friend—being required to rule in public on his colleague and roommate.

When the clerk read back O'Neill's words, it was clear they violated the rules of the House. The Parliamentarian ruled that they did in fact constitute unacceptable speech, and O'Neill was ordered to be quiet for the next 24 hours.

At that point Trent Lott, as the number two Republican in leadership, jumped up and said that no one would want to gag or embarrass the Speaker and asked unanimous consent that Speaker O'Neill be allowed to speak.

By this stage, O'Neill's staff and friends had finally gotten him to leave the floor and quit escalating the fight.

That night, thanks to C-SPAN, for the first time in history an internal house fight made all three national networks. Republican activists across the country saw a House GOP on offense for the first time in a generation. The seeds had been planted for what would (a decade later) become the House GOP majority.

Years later, after he had retired, Speaker O'Neill had lunch one day with Bob Walker.

"You and Gingrich owe me," he said cheerfully with a smile.

"What do you mean?" Bob responded.

"Until I attacked you, you were nothing but backbenchers. I made you into national figures," he recounted with a chuckle—and he was right.

C-SPAN will be incredibly lively the next few years as the radical younger House Democrats collide with the grandparents who currently run the House Democratic Party. There will be a lot of opportunities for Brian Lamb's invention to bring their government once again to the American people without editing and without distortion.

We all owe Brian, and his colleague Steve Scully, a big vote of gratitude for empowering citizenship in the television age.

Newt Gingrich was speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. He is now the host of the Newt's World podcast and the author of Trump's America: The Truth About Our Nation's Great Comeback. Follow him on Twitter: @NewtGingrich.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.