On February 14, 2018, a former student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas, a large public high school in the wealthy Parkland suburb of Miami, entered Building 12, the freshman building of his alma mater, and killed 17 people, including 14 students. It would become one of the top 10 deadliest shootings in U.S. history. Within hours, the media—now disturbingly efficient at this sort of story (it was the sixth school shooting in 2018)—had descended on the sleepy Everglades city.

In New York City, Dave Cullen was alerted to the shooting by a slew of texts from TV producers asking him to join the talking heads on their various news programs. Following the enormous success of his 2009 best seller, Columbine, Cullen had become the go-to "mass-murder guy," he says, and he had grown tired of explaining why these shootings keep happening and why they would probably never stop. Then he saw David Hogg, a Parkland senior, on TV, and he knew this was different.

That night on television, Americans heard little discussion about the shooter, Nikolas Cruz, and his motivations. Instead, they saw a group of remarkably poised and articulate teenagers repeating a unified message: We need gun control, and we need it now.

Within days, Cullen had flown to Florida to meet with the Parkland students and activists who would later form the March for Our Lives: Hogg, 17; Emma González, 18; Cameron Kasky, 17; and Jackie Corin, 17. He was there on a five-week assignment that turned into a yearlong project, culminating in his new book, Parkland: Birth of a Movement (Harper Collins).

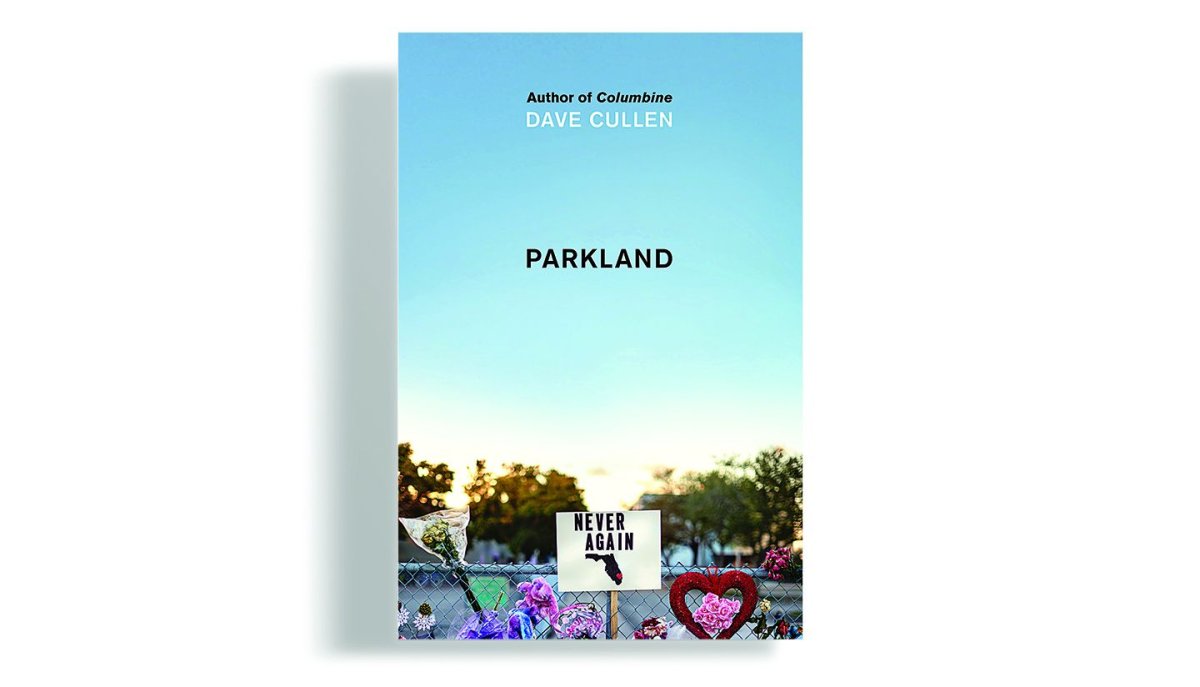

Columbine paints a vivid picture of two teenagers, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who plotted the first mass killing of this contemporary era of school shootings. Its successor picks up nearly two decades later with a new message—one about how to move forward. Columbine asked how this could happen; Parkland asked how we can make it stop.

Through a series of in-depth interviews and observations, Cullen shows how the student leaders of March for Our Lives, a group of enthusiastic theater kids, propelled fear and anger into a multi-month bus tour (their now-famous message: #NeverAgain) and began to change the national conversation on gun legislation that culminated in a nationwide protest on March 24, 2018. The Parkland kids, who grew up participating in active-shooter drills, were tired of defeatist attitudes (including Cullen's own) toward mass shootings, and they took charge of a situation that had gotten out of control. They stood up to the National Rifle Association, they stood up to governors and senators, and they stood up to gun rights activists who greeted them with hatred and AK-47s.

Cullen shows what it feels like to deal with teenage acne while fielding texts from George and Amal Clooney. He questions whether the burden of solving a seemingly unsolvable problem is too heavy for pubescent shoulders to bear. And he knocks readers out of their ennui. If a group of teenagers can stand up and fight for gun control—and for their very lives—why can't we?

Your admiration for the Parkland students really comes through. Did they seem unusual to you, or is their response something that could have happened elsewhere?

I did wonder: Are these just the most remarkable kids who happened to come together? And I kind of think they are. But also, sometimes naïveté can be your friend. These kids hadn't already been beaten down. A lot of adults are conditioned to fold before they start, but these kids hadn't been yet. They're not going to take no for an answer; they're not accepting the obvious. They're calling adults out on this, and I think some adults think it's refreshing and they're grateful.

Within 24 hours of the shooting, David Hogg had made himself more famous and more interesting than the person who attacked him. Hardly anybody I know can name the Parkland shooter. This is the first time in the history of mass shootings that this has happened.

There have been over 200 school shootings between Columbine and Parkland. Why did this one catch your attention?

I saw David on TV for the first time the morning after the shooting and was transfixed. I've seen and worked through two decades of victims' first-day reactions, and David did not seem typical. This was not normal—there had been nothing like it.

I called David that Sunday at noon, and he got on the phone with me right away, and we did a quick interview. Then he put me on the speakerphone with what would become the core March for Our Lives group, and Jackie [Corin] said, "I'm handling the bus trip to Tallahassee." And I was like, "Tallahassee? I thought you guys were going to D.C.," because they had just announced the march. But she said they were also going to Tallahassee to speak with local politicians. And so I got on a plane and was there the next day.

These were teenagers who were thrust into the spotlight and suddenly facing a ton of scrutiny, which, in a weird way, reminds me of Columbine: The first week after the shooting, even the FBI was investigating conspiracy because everyone assumed two high school boys couldn't have done all of that alone. It took them a week to come to the conclusion that it was just the two shooters. Nobody could believe these kids did it.

Twenty years later, and it's kind of the same thing. People said, "Obviously, these kids can't be organizing this thing by themselves. Who's really doing it and using them as pawns?" Anytime I'd post about being down in Florida, I would get responses like "I hope you're reporting on whoever is pulling the strings."

But it was, indeed, mostly these students organizing on their own, and they pulled off a lot. What made them so unique?

These kids were able to react the way they did because they were camera-ready. Between Snapchat and Instagram, they'd been trying out material for years—putting their content out there and doing stories since they were little kids. Everybody in their generation is a content creator. Not everybody is good at it, but these were mostly kids [who were in the school's theater group]. This was a team of creatives.

There was no social media when Columbine happened. How else did it play a part in the Parkland response?

During the shooting, the kids were on the phone with their friends asking, "What do you know?" Everybody was exchanging information. The school was organized into 13 buildings, so everybody knew people in other buildings, and they were madly texting. Kids can text, like, 37 people in 90 seconds, and they have these group chats. So it was a lifesaving thing to be on their phones, but it was also comforting to stay on and disconnect from the reality of the situation.

But then, after the shooting had ended and they were home, they got on social media. That was the big difference. Social media played a different role than people realized: It accelerated the "What should we do about it?" process. In past shootings, one or two friends would come together the next day. Now, they were connecting to hundreds of friends and reposting each other that afternoon and evening. Platforms like Facebook and Instagram played a huge role in making everyone realize that they weren't alone with their thoughts. Ideas were bouncing around, and so they all went to bed that night thinking: Why the hell does this keep happening, and why aren't the adults doing anything about it?

When the sun came up the next morning, they had already had the conversation with each other. And so when they went on TV, they were coordinated in their message.

It was the opposite of the Occupy Wall Street movement. They insisted on having one message and stayed on script.

The kids immediately knew they needed one voice in order to get their message across. It was just super obvious to them, because they are so much more intuitive about media messaging. These are pragmatic kids: They knew it wasn't just about expressing themselves; it was about the objective and team.

Listen, Marjory Stoneman Douglas is a huge school with about 3,300 students, and this wasn't just a randomly selected group of 20 kids from that pool. These are people who are very attuned to all of this stuff and were gifted enough to make this happen.

In the book, you talk a lot about the anger the Parkland students felt after the shooting. Was that a motivating factor?

The factor here that is different from all other shootings and helped spur the movement is that Parkland lasted for hours. Most mass shootings end within 10 to 15 minutes, and the victims usually experience a fight-or-flight rush. They have a run-for-your-life mentality and no time to be angry. Anger isn't on the priority list for most people; there are other things to deal with. But because the Parkland kids were trapped in their school for hours, they had time to stew over this. They're trapped in classrooms, and it's not a fight-or-flight thing because there's nothing for them to do; their brains aren't going to "How do I save myself from this?" because that's sort of a moot point. Instead, they're thinking: This is fucked up. Why the hell are we in here, and why does this keep happening?

And they have the space to be rational about it. Many of those kids told me they came out of that school in a rage because they had the time to go through a phase that a lot of victims don't have time to go through until a week after. The kids also had time to think: What are we going to do about this? That's why I was so transfixed by David Hogg when I first saw him on TV. I was thinking: This is not a first-day victim; this is not normal.

You also write about how the students figured out how to win their fight—by attacking fear.

The trip to Tallahassee was really eye-opening for them. Early on, it felt like this was all about momentum and not waiting years to actually see some action. The kids really thought that once politicians met them and heard what they went through, the politicians have to do something. Jackie quickly realized that it wasn't that the politicians were cold monsters who didn't care that a young girl was crying in front of them. She saw that there was something much more terrifying stopping them: their fear of the National Rifle Association.

In your book about Columbine, you talk about the many high school–aged kids who became obsessed with the killers.

Oh totally. They call themselves the Columbine True Crime Community, and they're alive and well. Before Parkland, I was blocking 30 to 50 of these people each week on social media. After each big shooting, they pause for a week or two, and then they'll come back. They never came back after Parkland.

Are you hopeful about the future of gun reform in our country?

My job over the past 20 years has been to explain why gun reform is impossible and hopeless. It was so refreshing to go down to Florida and be with these kids who called bullshit on everything I've said for decades. It made me think that maybe I had accepted defeat too soon. That's the gist of their whole movement: You adults threw in the towel years ago, so fuck you, get out of our way, and let us have a go at this.

So how do we end mass shootings?

There seem like three potential roads out of the epidemic, and the solution will probably be some combination of the three.

The first is gun control. The second is the media diminishing the images of the killers—to stop feeding [their egos] and inadvertently making heroes out of them. And the third is a screening for teenage depression. Why don't we give these kids a screener in their homeroom classes once or twice a year? It could be a single-paged form—10 questions, like "How many days this week have you felt sad?" or whatever. It's a simple scoring; every school could do it at no cost. This is low-hanging fruit. The lesson we've learned from Columbine is that it's usually suicidally depressed people who become shooters.

Parkland: Birth of a Movement (HarperCollins) is available here.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Nicole Goodkind is a political reporter with a focus on Congress. She previously worked as a reporter for Yahoo Finance, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.