On the eighth day of 2016, David Bowie released his final album, the remarkable Blackstar. On the 10th day, David Bowie died, succumbing to a cancer that had been kept secret outside of the icon's inner circle for more than a year. And on the 11th day—the next day, pun intended—the world fell into mourning. And listening. And celebrating. But mostly mourning.

This was essentially the default status of the music industry in 2016: listening, and also mourning.

In retrospect, Blackstar seems inevitable, as though Bowie's end and 2016's start were long prophesied in hieroglyphics in an ancient cave. Bowie's untimely death, linked in time with Bowie's best album since probably the Carter administration, offers a neat microcosm of the music world this year: a constant boomeranging between grief and awe. Rarely have more great artists (a handful of irreplaceable icons among them) died in a single year. Rarely have more great artists (a handful of top-shelf pop stars among them) put out albums in the same year.

Related: The great celebrity death epidemic of 2016

Lamenting the cruelty of 2016 has become a social media cliché. When Leonard Cohen and Sharon Jones died a week apart, we tweeted things like "2016 just gonna keep on 2016ing, huh?" When we saw Bob Dylan trending one morning, we felt an instinctive shiver of dread. (False alarm! He won a Nobel!) When two of the three members of Emerson, Lake & Palmer died in the same year, we half-jokingly urged Carl Palmer to run for cover. And when we lost Prince, one of the more morbid reactions was to wonder who's next. Has Cher seen a doctor lately? Has Keith Richards cut back on the cigarettes?

How is David Byrne doing? Is he in good health? Can we get well checks? Cher, how are you? Stevie? Chaka? Elton? Willie? Go to the doctor.

— Jessica Luther (@scATX) April 21, 2016

On the spectrum of tiresome, quintessentially 2016 tropes, grumbling about music deaths falls somewhere between likening Trump to Lord Voldemort and making a Harambe joke.

So it's cold comfort in a year marked by death and destruction, but 2016 produced two of the greatest farewell albums in history. Bowie's Blackstar and Leonard Cohen's You Want It Darker are as astonishing as any musical goodbyes since the death of Johnny Cash.

During the early 2000s, the Aging-Songwriter-Comes-to-Terms-With-Mortality-on-Farewell-Album trope became something of a cliché. (To be clear: I am talking about death. I am not talking about final albums from bands on the verge of breaking up, though if I were, I would single out Sleater-Kinney's The Woods and Talk Talk's Laughing Stock among the very best.) Johnny Cash released American IV: The Man Comes Around, the final album of his lifetime, in late 2002. The Man in Black died less than a year later. By chance, Warren Zevon died the same week as Cash, just 12 days after releasing his own farewell album, 2003's The Wind. The most emotionally arresting track on there is a song called "Keep Me in your Heart," in which Zevon acknowledges his terminal Mesothelioma diagnosis and pleads with loved ones to "hold me in your thoughts / Take me to your dreams." It is the final song he ever wrote and recorded.

The fall of 2003 was also when we lost Elliott Smith to a grisly apparent suicide. When Smith's final album, From a Basement on the Hill, appeared posthumously a year later, it was tough not to hear traces of death all over it. (One critic later remarked that the "foreshadowing of his suicide is so strong that it's difficult to listen to.") Smith's producer and ex-girlfriend pieced the sprawling collection together after his death; the highlights include "A Fond Farewell" ("It's just a fond farewell to a friend / Who couldn't get things right") and "King's Crossing," where he seems to dare listeners to pull him back from the edge: "Give me one good reason not to do it."

Is scanning for clues in the final recordings of artists who died young a morbid and reductive exercise? Sure, often it is. But how can you listen to records like Basement on the Hill or Nirvana's In Utero or Amy Winehouse's posthumous Lioness: Hidden Treasures collection and not sense some impending doom?

Cash's The Man Comes Around might be the most acclaimed farewell album ever—at least prior to Blackstar—which is interesting, since it is primarily an album of cover songs. Some of the selections, like Depeche Mode's "Personal Jesus" and Simon & Garfunkel's "Bridge Over Troubled Water," are well-known already. To say that Cash makes these songs his own would be a tremendous understatement. As on his prior collaborations with Rick Rubin, Cash strips the songs to their skeletal essence: an acoustic guitar, some piano and an iconic voice, grizzled but not gone. What's compelling about this album is the obvious tension between Cash's frail delivery and the youthful innocence of the source material. The Beatles' "In My Life" is transformed from a wistful ode to childhood nostalgia to an old man's reflections on the people and places he has known. When Trent Reznor sang "Hurt," it was from the perspective of a heroin addict staring down suicide. Johnny Cash's "Hurt" is a haunting deathbed lament that has become more recognizable than the original. The video, which intercuts an aged Cash with visions from his past, is frequently regarded as the best music video ever.

It is rare for any popular recording to address mortality with such naked candor. The strange pull of The Man Comes Around is that it reframes the familiar in a new context. Bowie's Blackstar, by contrast, obliterates the familiar. It contains zero nostalgia for Bowie's greatest hits. No covers. No throwbacks. What critics first noticed was the experimental, jazz-heavy arrangements: frantic ("Sue"), elegiac ("Lazarus"), epic ("Blackstar"). At the end of his career, Bowie was still ricocheting into the strangest unknown. As for the lyrics, they are obsessed with death, though never straightforwardly so. Bowie, who was battling cancer as he recorded these songs, veiled his meanings in enigmatic imagery ("Look up here, I'm in heaven / I've got scars that can't be seen"), wordplay and even one song sung in "Nadsat," the fictional language used in A Clockwork Orange. The symbol-rich title track describes a public execution and a spirit risen upon death. "Lazarus," with its funereal trumpets, delivers a cryptic warning: "Look up here, man / I'm in danger."

"Dollar Days," the penultimate number, climaxes in a maelstrom of bleating saxophone. The song's thick imagery is littered with glimpses of some cruel inevitability: "If I'll never see the English evergreens I'm running to / It's nothing to me." Bowie repeats the words "I'm dying to" (as in, "I'm dying to / Push their backs against the grain…") so many times that the double meaning clearly emerges.

Related: David Bowie left hints about his death on eerie new album Blackstar

For much of his career, Bowie's genius had as much to do with style and imagery as it did music. With Blackstar, he unveiled a new and unsettling iconography: the five-point star of the album cover, the vision of Bowie lying in a deathbed with bandages over his eyes in the "Lazarus" video, the shot of him retreating into that mysterious wardrobe. Blackstar, by chance or design, is the first Bowie album in 49 years of recording not to feature the artist's image anywhere on the cover art.

What was more staggering than the music was the timing. The album appeared on Bowie's 69th birthday. Two days later, he died. Never has there been such a neatly choreographed musical goodbye. (The timing was so eerie that fans wondered whether it was possible he had in fact delayed his death.) Tony Visconti, Bowie's longtime producer, confirmed that the album was meant as a sort of farewell. "His death was no different from his life—a work of Art," Visconti wrote on Facebook. "He made Blackstar for us, his parting gift. I knew for a year this was the way it would be."

* * *

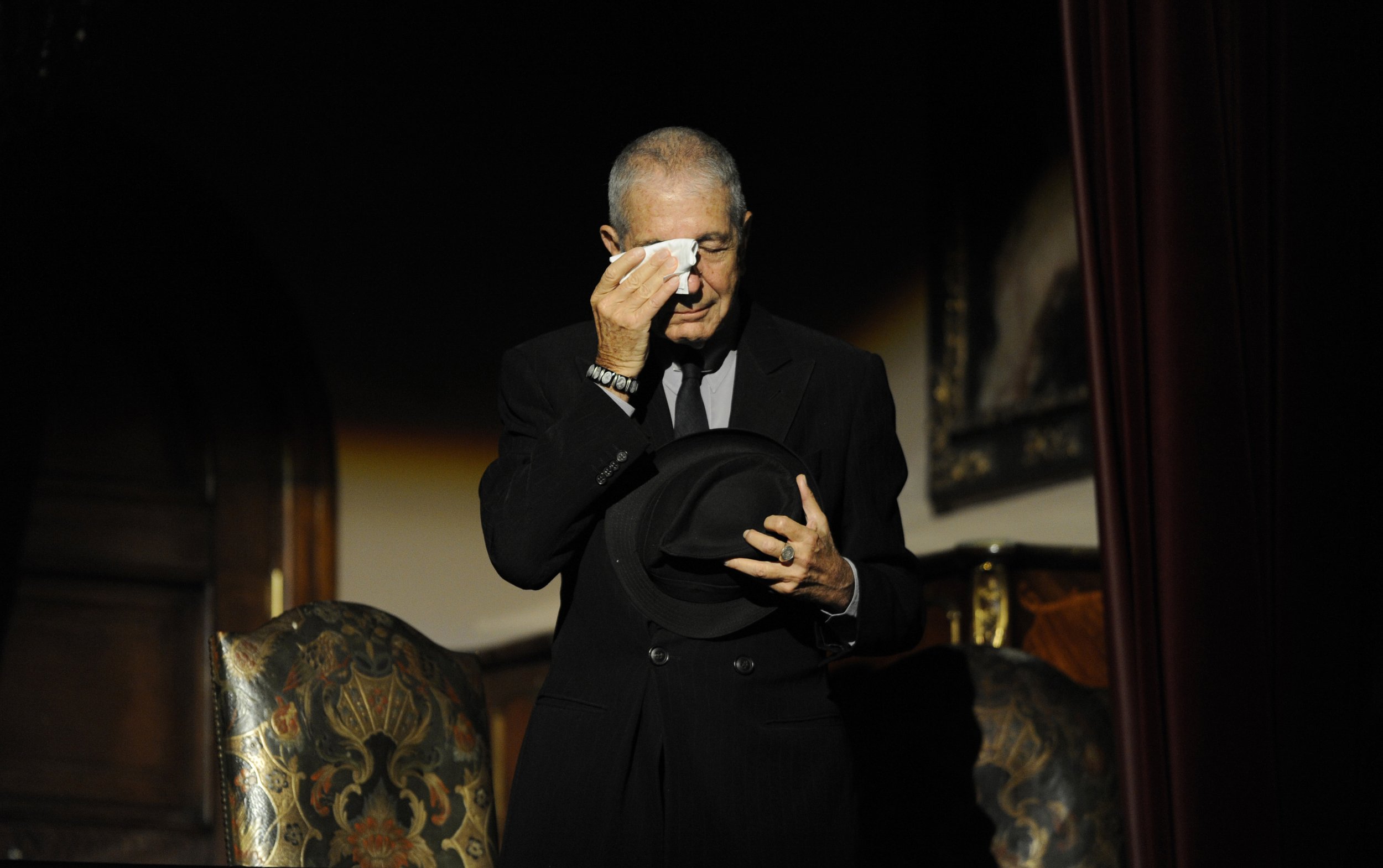

On one of the earlier entries in his American series, Johnny Cash covered "Bird on the Wire," a song that Leonard Cohen wrote as a young man living on the island of Hydra. As an old man half a century later, Cohen recorded his own farewell album. In September, the Canadian songwriter turned 82. In October, he released You Want It Darker. (This was the month he was profiled in a long New Yorker piece. Memorably, he told David Remnick, "I am ready to die." He waved away any knowledge of the afterlife.) In November, he was gone.

There are no birds on You Want It Darker. There is not much romance or erotic longing. "The most jarring thing about Darker," Pitchfork's Stacey Anderson observed, "is how utterly devoid of lust it is." On a devastating waltz called "Leaving the Table," Cohen confronts his spent libido with resignation and some wistful pedal steel: "I don't need a lover, no, no / The wretched beast is tame." When he does seem to address a lover, on the song "Treaty," it's tainted with remorse: "I'm so sorry for that ghost I made you be." The album is heavy and reflective but also fast-moving and, like Bowie's, full of bold experiments: The title track, for instance, pairs an electronic beat with the vocals of a synagogue choir.

It's a risky thing to identify any single Cohen album as his farewell. His music has been suffused with mortality and death for decades. In "Tower of Song," he lamented, "My friends are gone and my hair is grey / I ache in the places where I used to play." That was 1988. He lived another 28 years. Nearly every Cohen album since then has been erroneously interpreted as a farewell. Dear Heather, in 2004, was widely assumed to be his last. So was 2012's Old Ideas, which opens with a funny, wry song about "Going Home," in the spiritual sense. By 2014's Popular Problems, fans caught on: He was speeding up his creative process while he still had the time. Remarkably, at an age when most songwriters snooze into retirement, Cohen, the elusive perfectionist, toured and put out three great albums in the span it takes U2 to make one. Maybe You Want It Darker was intended to be his last. Maybe not. Remnick's profile reported that he had unfinished lyrics he hoped to finish or record.

What You Want It Darker has in common with Zevon's The Wind is that it was partly recorded at home because the singer was too frail to travel to a studio. (The New Yorker profile revealed that Cohen suffered from painful compression fractures in his back, which rendered mobility difficult. His son Adam set up a makeshift recording studio at his home in Los Angeles; Cohen sang into a microphone placed on the dining room table.) What Darker has in common with The Man Comes Around is that the vocals shake with frailty and death. This is not a criticism. Cohen was never known for having a pleasant or versatile voice in the first place. (As one fan famously quipped, "No one can sing a Leonard Cohen song the way Cohen himself can't.") But as he grew older, his voice became deeper, more unsparing, more suited to the work. It is impossible to imagine 1992's "The Future" sung in anything but that apocalyptic grunt. It's as if Cohen's voice finally caught up with the dark intensity of his songs.

On this recent spate of releases, the voice is an extraordinary growl. Cohen sounds elderly and wizened but not defeated. On Darker, it is hard not to hear a startling proximity to death in these vocals. The gruff whisper is at its best on the stormy title track, in which Cohen repeats an ancient Hebrew expression of spiritual readiness: "Hineni / Hineni / I'm ready, my lord."

It's too much for us to expect this from our musical heroes. Their deaths are not ours. We're not owed any parting gifts. In fact, Cohen's most wrenching farewell was initially intended to be private. It was a letter he sent Marianne Ihlen, his once-muse, over the summer when she was dying of leukemia. "Well Marianne," he wrote, "it's come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine."

When those words were read to her, she lifted her hand, as if reaching out. Within days, she was gone. Three months later, Cohen kept his promise.

Read more on Newsweek.com:

- David Bowie left hints about his death on eerie new album 'Blackstar'

- Leonard Cohen's 20 best songs

- Adrian Belew on working with David Bowie: 'No one will ever replace him'

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.