About two-thirds of the way into the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art's David Bowie show, the visitor encounters an exhibit devoted to his 1979 Saturday Night Live performance of "The Man Who Sold the World" that's like a cluster bomb, slicing every which way through the artist's multifaceted career. The show was recorded on December 15, the end of the 1970s and a transitional year for Bowie—as were most of them. Having been written off by punk rock ("'Come on and show me,' say the bells of old Bowie," Joe Strummer sneered in 1978's "Clash City Rockers"), he had returned from his Berlin exile stronger and weirder than ever, and seemed poised to watch punk die—or at least morph into something else.

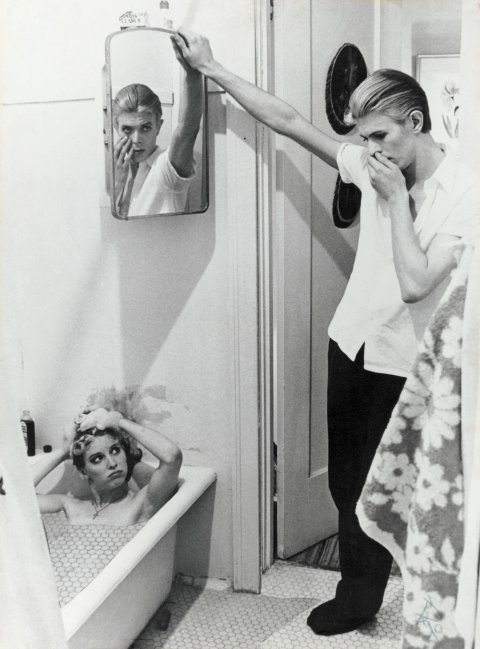

The song was a revamped version of the title track of his 1971 album—the U.K. jacket featured Bowie in a self-designed man-dress that his U.S. label thought Americans weren't ready for (and this for the nation that gave the world Little Richard, an early Bowie influence). It was never a hit (despite its catchy opening hook and enigmatic chorus: "Oh no, not me/I never lost control…"), and if his SNL performance seems wooden, it's because he is wearing (or more accurately standing in) a heavy cardboard space tux, designed by Mark Ravitz and Bowie, and inspired by costumes from a 1923 production of Tristan Tzara's Gas Heart. His backup singers—German countertenor Klaus Nomi, in futuristic samurai makeup, and downtown New York drag artist Joey Arias, in a dress, of course—had to carry him to the mike to begin singing: "We passed upon the stair/And spoke of was and when…"

It was a moment that synthesized a number of the 67-year-old singer's influences—punk, drag, Dada, sci-fi—and hardly scratched the surface. Like the traveling show it's part of, the video and accompanying costumes and memorabilia remind the visitor of just how many multitudes the man contains. "I didn't realize how involved he was in shaping all those characters and the collaborators he brought in over the years," says MCA curator Michael Darling. He saw the show, David Bowie Is, in its original incarnation at London's Victoria and Albert Museum and was immediately hooked. "His story of constant reinvention is something I have a soft spot for." (Bowie has an album of new material, The Next Day, and a best-of boxed set, Nothing Has Changed, out now.)

Darling rearranged some of the show's objects (all taken from the artist's extensive archives), breaking out Bowie's key music videos for instance (such as Julian Temple's short film Jazzin' for Blue Jean, featuring "Screamin' Lord Byron"), and "because of American audiences we made a much bigger deal of his SNL appearance than in other venues." (The show traveled to Toronto and Brazil before landing in Chicago, where it will be until January 4, 2015; future venues include museums in Paris, Japan and Australia.)

David Bowie Is was sold out in London, so Darling did not expect to have the only American venue; he was surprised that other museums weren't fighting for the rights. "I'm a fan of finding a hook that can bring broader audiences into a contemporary art museum," says Darling. "We just got there early, were serious from the beginning and locked in some dates."

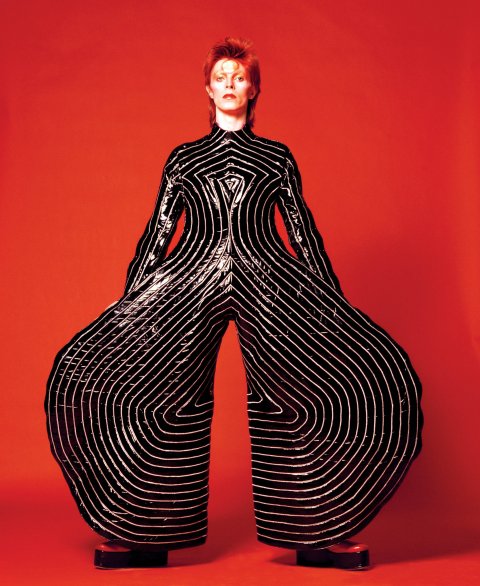

Sennheiser headphones and a small guidePORT receiver are required when taking the tour; the multimedia design is motion-activated—approach a towering video of a Top of the Pops performance of Ziggy Stardust (Bowie) and the Spiders From Mars doing "Star Man" in 1972 and you'll hear them in their thundering glory (the teenyboppers frugging in the background seem to be having their minds blown); move a step away and watch an interview with Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto, who designed the costumes for the 1973 Aladdin Sane tour. Dancing breaks out regularly, and in the show's final room, a cavernous concert space, several filmed live performances are shown at once. Choose a decade and get in the groove.

There aren't too many stars of Bowie's stature who would stand up to this treatment. From his first album (released on the same day in 1967 as the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band), he had a hand in designing the covers, costumes, sets and later videos in each phase of his career. He took a stab at being a commercial artist as a teenager and found the reality "diabolical…. I never realized being an artist meant buckling under so much." His control of his artistic personae has been absolute, even as he has allowed collaborators and fellow musicians to riff and improvise around him.

The costumes that stand sentinel throughout the show—Alexander McQueen's tattered Union Jack coat from the 1997 Earthling album and tour; Freddie Burretti's ice-blue suit for the 1972 "Life on Mars?" video—are like skins shed by the artist. Darling has placed them in a chronological order, and the effect is impressive. "His constant reinvention and destruction of these different characters was really an important part of the story," he says.

"Ashes to Ashes," from Bowie's 1980 Scary Monsters…and Super Creeps, was a No. 1 hit in the U.K., and the song "seems to close the cycle that began with Space Oddity 11 years before," writes Jon Savage in an essay included in the show's coffee-table book (David Bowie Is Inside). The video for "Ashes," co-directed by Bowie and David Mallet, is shown with accompanying costumes and handwritten lyrics; more than 30 years after its debut on MTV, it is still a three-tiered revelation. We see the singer in a padded cell, dressed as Pierrot by a psychedelic seashore and as a housebound spaceman in a bleak, black-and-white 1950s kitchen. Bowie, who had gone from L.A. to Berlin to overcome a cocaine addiction, was probably being as autobiographical as he ever gets in the lyrics: "Ashes to ashes/Funk to funky/We know Major Tom's a junkie…" In a machine-gun move he mows down his former selves to be born again, walking off with a bunch of New Romantics (the Culture Club crowd that found inspiration in Bowie's example) to an almost idiotic nursery rhyme refrain: "My momma said, 'To get things done/You better not mess with Major Tom.'"

"He wasn't frightened to do anything that was surreal," said Mallet of making the video. "He wasn't frightened to go back to French silent, surrealist movies. He wasn't frightened to do anything."