A string of crises have hit U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron's government in recent weeks, potentially damaging the campaign to keep Britain in the European Union ahead of a June 23 membership referendum.

This week, it was continued questioning over Cameron and his father's finances that had the usually-unruffled politician on the front pages for all the wrong reasons. Before that, it was the malaise settling over Britain's once-proud steel industry , when Indian Tata steel said it would be withdrawing from its British businesses, risking thousands of jobs.

All this came after the resignation of former Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith, who in an extraordinary interview on the BBC's Andrew Marr Show said the government was in danger of "drifting in a direction that divides society rather than unites it."

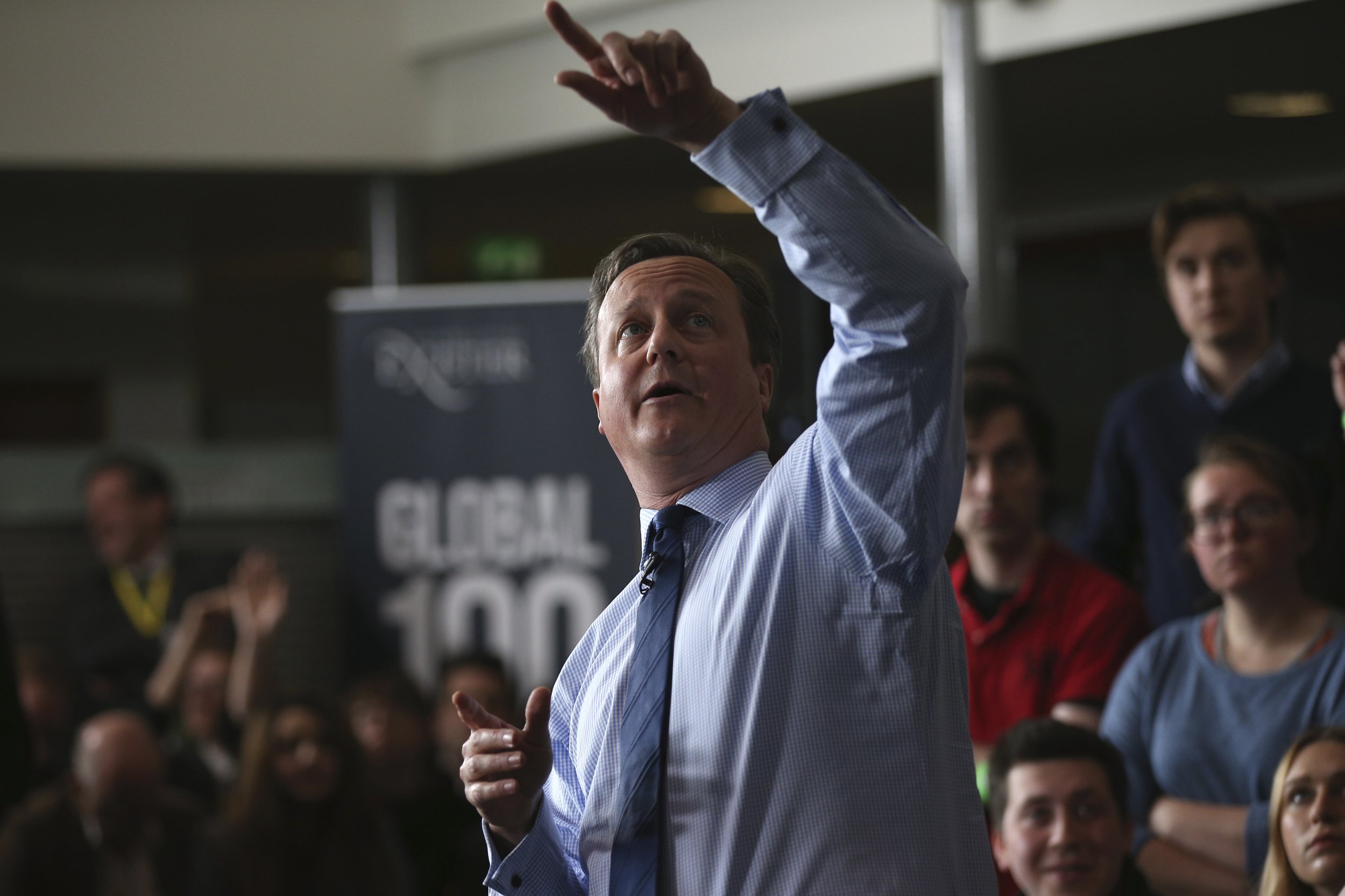

The problem for those who want Britain to stay in the EU is that Cameron, who backs a Remain vote in the referendum, is one of the campaign's most important spokespeople. By extension, what harms him could help Brexit. So as his approval rating slides to -24 percent in a YouGov poll, lower for the first time than controversial opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn, campaigners on both sides are watching for the effects.

"Of course, it is a worry that the anti-Cameron, anti-Europe press will do anything between now and June 23 to disable him and [Chancellor George] Osborne," says Peter Mandelson, a former Labour government minister and a prominent campaigner for a Remain vote. "Basically, you have a combination of the left press attacking them because they are Tories and the rightwing press attacking them because of Europe." Meanwhile, a source within the pro-Brexit U.K. Independence Party (UKIP) says he thinks the savaging of Cameron will help Leave "significantly."

Campaigners on both sides might be expected to play up the impact of individual events. Matthew Goodwin, professor of politics at the University of Kent, says that criticism of Cameron over his finances in particular may not have much impact, as "the suggestion that David Cameron is part of a wealthy elite is already priced into British politics." But, he says, "we know that dissatisfaction with the government is on the rise… that is significant as a backdrop to the referendum, especially if we remember that referendums are often influenced by general opinion toward the incumbent government of the day." While, therefore, Cameron's crises may not wildly swing the vote towards Leave, they are, says Goodwin, "not particularly helpful" for the Remain camp.

So whether Cameron drives significant numbers of votes away from Remain or not, what's certain is that he has been much less of a boon than some expected to the Remain campaign.

From the beginning, most of those working to keep Britain in Europe were confident that Cameron would go their way, even though he kept insisting that he "ruled nothing out" in terms of potentially campaigning for a Leave vote until he had completed a renegotiation on Britain's terms of membership.

There was reason to expect that when the prime minister returned from Brussels with that deal, voters might trust in what he had to say. The Conservative leader had unexpectedly led his party to its first majority general election victory since 1992 only a year before. The pollster YouGov found throughout 2014 and much of 2015 that voters were more likely to back a Remain vote on the condition that Cameron recommended it after he had "renegotiated our relationship with Europe and said that Britain's interests were now protected."

It didn't happen. The changes in the deal, when its final incarnation was announced on February 20, were technical and relatively small. Independent experts, including the IPPR think-tank, said that new rules on welfare benefits for EU migrants would not significantly reduce immigration, one of voters' primary concerns. The right-wing press—who, while never the biggest fans of relatively liberal Cameron, could often previously be counted on to back him—tore into his changes. "Call that a deal, Dave?" Read the front page of the influential Daily Mail.

Voters weren't impressed, and no significant bounce materialized. "If the renegotiation was designed to give Remain a surge of support then the evidence suggests that it failed to do so," says Goodwin.

As referendum day approaches, Cameron's party, and government, is divided, his media stock is lower than at any time during his premiership, and voters are starting to look seriously at the choice facing them in June. The polls show that there's still everything to play for, but the prime minister badly needs to reinstate a sense of control and authority if he's to deliver the resounding victory he thinks the country needs.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Josh is a staff writer covering Europe, including politics, policy, immigration and more.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.