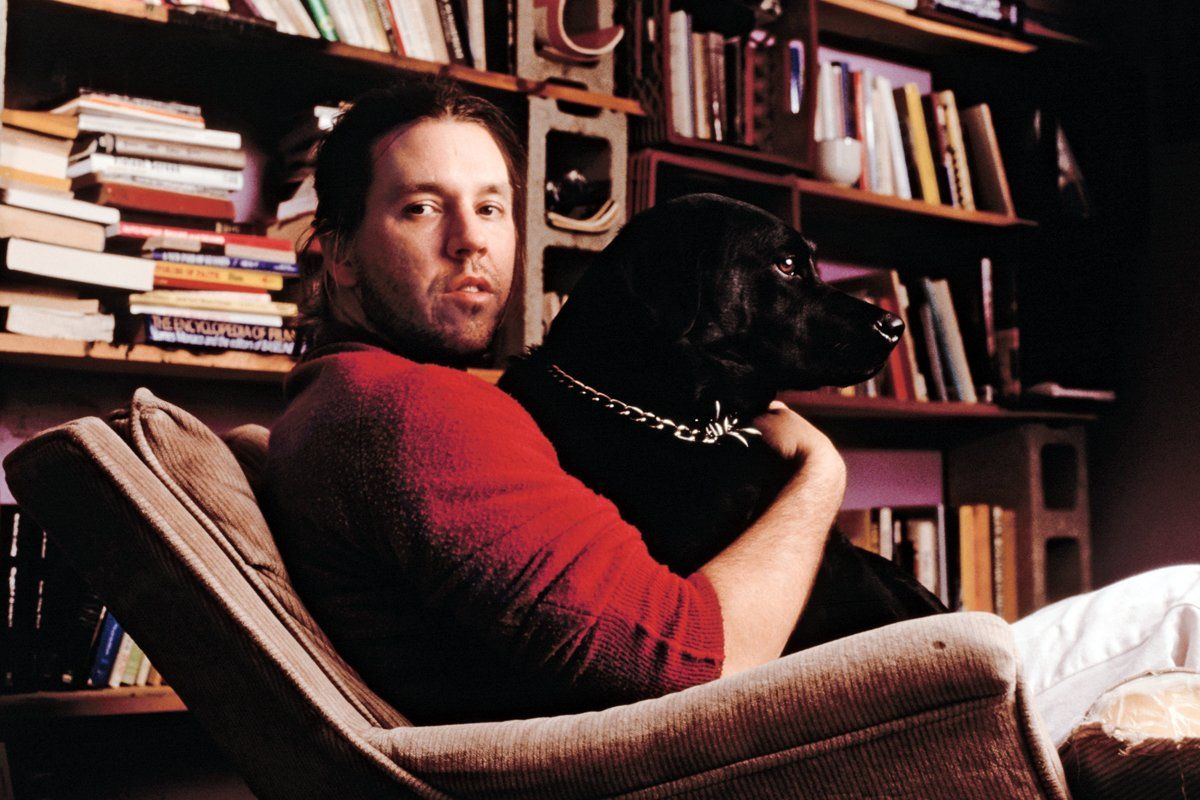

In 1990, David Foster Wallace, only 28, had already lived a chaotic life: he'd been a literary star, a teacher, and a depressive, had attempted to take his own life and then found his way into drug and alcohol rehab. After a month in a facility, he had entered a halfway house in Brighton, Mass. His collapse had taught him that the things that had once mattered most to him—cleverness, facility, pyrotechnics—were no longer enough to sustain him. But if he wasn't supposed to light up the page with his brilliance, how was he supposed to write?

The only thing Wallace knew for sure was that he desperately wanted to be a novelist again but some piece of him still felt too fragile to attempt an effort so key to his well-being. The problem, he felt, was not really the words on the page; he had lost confidence not in his ability to write so much as the need to have written. Jonathan Franzen, with whom he had struck up an epistolary friendship, offered to get together that April when he was in Boston. Wallace said fine but stood him up after they made plans. But because one tenet of recovery is to make amends to those you have wronged, he wrote to his friend explaining his behavior. "The bald fact is that I'm a little afraid of you right now," he wrote. He begged to be allowed to bow out of their embryonic competition, to declare a truce against this writer who was so "irked by my stuff," because Wallace was no longer "a worthy opponent in some kind of theoretical chess-by-mail game from which we can both profit by combat."

He went on: "Right now I am a pathetic and very confused young man, a failed writer at 28, who is so jealous, so sickly searingly envious of you and Vollmann and Mark Leyner and even David F--kwad Leavitt and any young man who is right now producing pages with which he can live ... that I consider suicide a reasonable—if not at this point a desirable—option with respect to the whole wretched problem."

His avoidance of his only literary friend made him mad at himself, but to be sitting at a table discussing how to create art would be an inherently false gesture, he felt, because, as he explained to Franzen, he was no longer really an artist: "The problem's details are at once shameful to me and boring to anyone else. I always had great contempt for people who bitched and moaned about how 'hard' writing was, and how 'blockage' was a constant and looming threat. When I discovered writing in 1983 I discovered a thing that gave me a combination of fulfillment (moral/aesthetic/existential/etc.) and near-genital pleasure I'd not dared hope for from anything."

Franzen quickly wrote to reassure him there were no hard feelings. He had only been hoping for "some laffs and companionship from a late afternoon with you in Cambridge." He too had felt "joyless" in his writing lately. Wallace, though, like a cancer patient having to explain himself to a headache sufferer, did not think their discomfort was equivalent. His anguish, he wrote, had multiple sources, from a fear of fame to a fear of failure. Behind the ordinary fears lurked the fear of being ordinary.

Even as Wallace was complaining that he had lost his old reason for writing, Franzen in his letters was quietly suggesting a replacement. He would remind Wallace of the pleasure Franzen took in creating characters he loved and how the stories he had liked in Girl With Curious Hair, Wallace's story collection, had given him the same satisfaction; both were part of "the humble, unpaid work an author does in the service of emotion and the human image." A year before when Franzen had suggested something similar, Wallace had dismissed it as twaddle. Back then—in a letter in which he said for all he cared readers frustrated by his writing were welcome to think he was an asshole—he had made clear that "[f]iction for me is a conversation for me between me and something that May Not Be Named—God, the Cosmos, the Unified Field, my own psychoanalitic cathexes, Roqoq'oqu, whomever. I do not feel even the hint of an obligation to an entity called READER—do not regard it as his favor, rather as his choice, that, duly warned, he is expended capital/time/retinal energy on what I've done."

But now he wondered if his resistance toward a more supportive idea of the writer's relationship with the reader wasn't the cause of his blockage. He responded to Franzen: "I'd love to hear more on what 'humble, unpaid work an author does in the service of emotion and human image' is ... And how, as a vastly overselfconscious writer, might one still go on having faith and hope in literature and some kind of pleasure ... ? I admit it: I want to know. I have no clue. I'm a blank slate right now. Tabula rasa or whatever."

Wallace stayed in the halfway house for six months. After, he faced the ordinary expenses of a Boston-area resident. He was back against a problem he knew well—that if he taught he might not write, but if he didn't teach he would not eat.

Someone new had come into his life though, as if to counter this disappointment: Mary Karr, a poet. The Texan-born Karr was in her mid-30s, seven years older than Wallace. She lived in Belmont, Mass., drove a station wagon, and had the stability and the grit that Wallace felt he lacked. They had, in fact, met briefly before, and he was very taken with her; she was witty and had a raunchy vocabulary. Soon after he moved out of rehab, he saw her at a meeting. It seemed like serendipity. He quickly grew infatuated. Wallace was well aware of the warnings against pursuing another person newly in recovery. It did not matter to him: here was a kindred spirit, another writer struggling to surrender to a greater power but for whom phrases like "One day at a time" and "Do what's in front of you to do" hurt the brain.

Karr volunteered at the halfway house, so Wallace often had occasion to see her. Immediately he wanted to be involved, but Karr, who was in a shaky marriage and trying to protect her son, says she had no interest. She sensed instability and trouble. "We were both just shocking wrecks," she remembers; he bragged that he had perfect SATs, and called her Miss Karr "in this obsequious, Charlie Chanish fawning kind of way." He saw her, she realized, as some sort of mother/redeemer figure.

Wallace did not hear subtle variations in no; he knew only one way to seduce: overwhelm. He would show up at Karr's family home to shovel her driveway after a snowfall, or come unannounced to her recovery meetings. Karr called the head of the halfway house and asked her to let Wallace know his attentions were not welcome. Wallace besieged her with notes anyway. He called himself Sorrowful Werther. She was Sainte Nitouche, the saint who cannot be touched, a reference to her favorite book, Anna Karenina. She felt an affinity for him, considered him brilliant but also unsound. One day, she remembers, he arrived at a pool party she was at with her family with bandages on his left shoulder. She thought maybe he had been cutting himself and wouldn't show her what was underneath—a tattoo with her name and a heart. He clearly felt he had made a commitment there was no retreating from. The details of the relationship were not clear to others though: Wallace told friends they were involved; Karr says no. She too steered Wallace to a new course in his fiction. "His interest in cleverness was preventing him from saying things," she remembers. She told him not to be such a show-off, to write more from the heart. One time when he told her that he put certain scenes into his fiction because they were "cool," she responded: "That's what my f--king five year old says about Spiderman."

For nearly two years Wallace had been living a hectic, unbalanced life. If he was no longer a substance abuser, he was still a drama junkie, a man afraid to be alone with his own thoughts. Then in the spring of 1991 Karr left with her family for Syracuse, N.Y., where she had a teaching job. With Karr gone for good—she says she and Wallace had already not been in touch for some time—Wallace collapsed. It was his first breakdown since quitting drinking, and it devastated him. In November 1991 he was admitted to a hospital psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of suicidal depression. He lay in a locked ward for several days. His doctors increased the dose of Nardil, the antidepressant he was on, and he began to improve. After two weeks he was released.

Wallace never forgot his literary hopes. Throughout 1990 and into 1991 he had fought off the worry that, sober, book reviewing and essays were all he was capable of. He wrote to his agent, Bonnie Nadell, as much to reassure himself as her, that things would change.

"Please don't give up on me. I want to be a writer now way more than in 1985. I think I can be better than I was but it's going to take time—and believe me, I know that quite a bit of time has elapsed already ... Do not assume, please, that I am being slothful or distracted because I have not sent you any fiction to publish. Do not assume I've given up in despair, or that I've burned out. I haven't, I swear. It may be a couple more years before I finish anything both long and respectable, but I will. Please don't forget me, and please don't let Gerry [Gerald Howard, his editor] forget me either ... I write daily, on a schedule, am at least publishing hackwork and I will be a fiction writer again or die trying."

The breakthrough for Wallace came when he was able to assimilate the suggestions that Karr and Franzen were making. His new commitment to single-entendre writing, writing that meant what it said, brought with it a surge in confidence Wallace hadn't felt in years. Neither his breakdown in November nor Karr's departure for Syracuse could hinder it: in fact it may even have been the spur, leaving Wallace with the need to prove he deserved her love. He later wrote about the following year in the margin of a book, "The key to '92 is that MMK was most important; I[nfinite] J[est] was just a means to her end (as it were)."

There is no clear start date for Infinite Jest. Pieces of the novel date back to 1986, when Wallace may have written them originally as stand-alone stories. The novel contains all three of Wallace's literary styles, beginning with the playful, comic voice of the college years that produced The Broom of the System, passing through his infatuation with the postmodernism of his graduate student years at the University of Arizona (Girl With Curious Hair), and ending with the conversion to single-entendre principles of his days in Boston. Once Wallace had his third approach, he seems to have worked with remarkable speed because by April 15, 1992, he had a proposal and a partial manuscript of Infinite Jest ready for Nadell. He was not just in the grip of inspiration. The point was to get a contract for the book. It was "the bravest thing" he had done since getting sober, he would later tell an interviewer, but he believed the work was going so well that he could deal with the pressure.

By the spring of 1992 Karr's marriage was finally at an end, and Wallace had new hope that he could be at her side. He was ecstatic. He was ready to leave Boston. If he could get an advance, he could have the life and the woman he wanted. He had suffered beyond what he knew possible for her, and the suffering felt like an act of absolution.

A month later, in May 1992, Wallace packed up what little he had and drove to Syracuse. He had rented an apartment in a house around the corner from Karr. It was in a typical graduate-student neighborhood, full of warping clapboard houses and right across from the food co-op. But being near the woman he loved made all the difference.

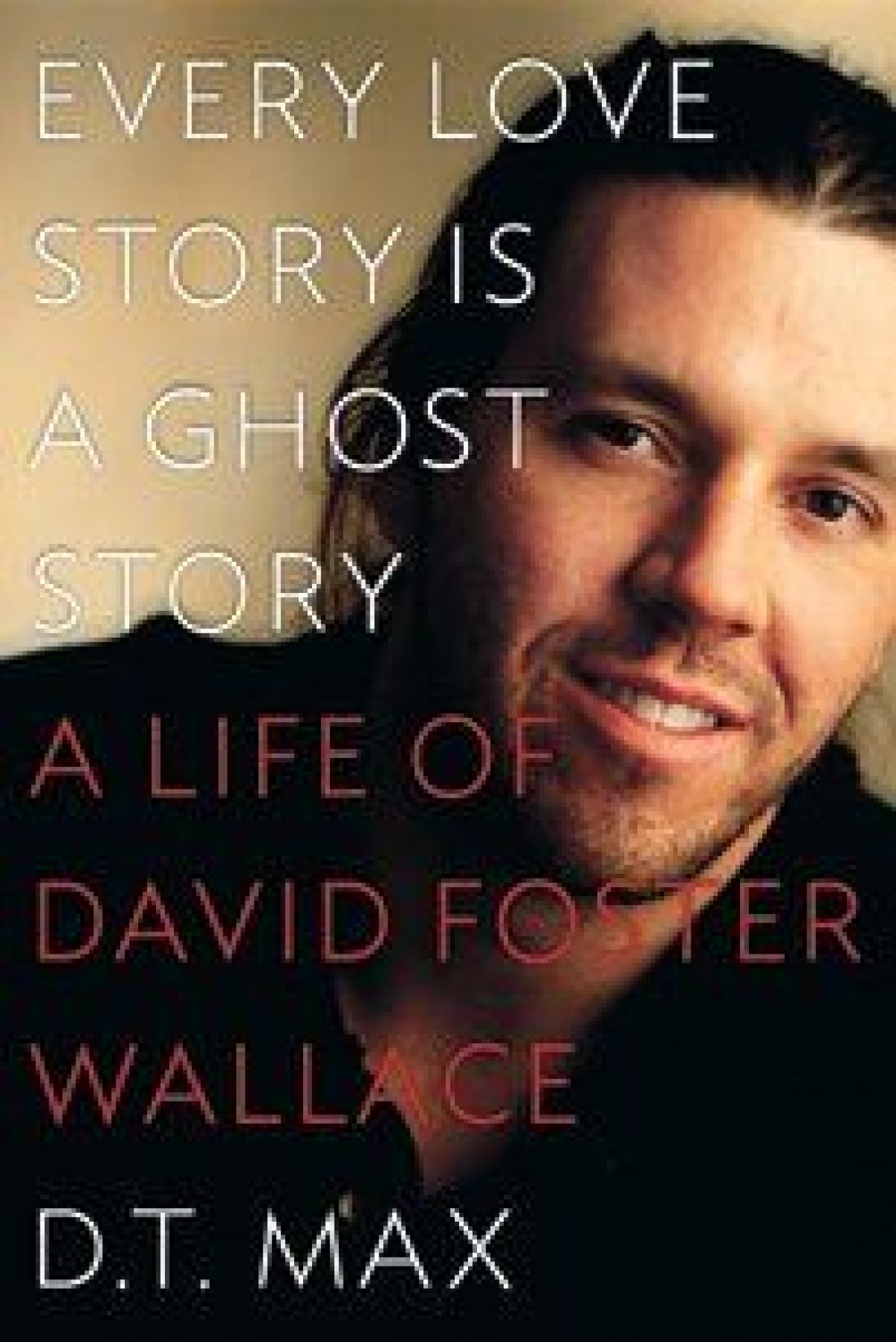

Wallace and Karr would pursue a tempestuous relationship in Syracuse and ultimately break up, as he continued his work on Infinite Jest. The book would take him several more years. But when it was published in 1996, it was a phenomenon, a novel so "spectacularly good," wrote Walter Kirn in New York, it "obliterated" the competition. Its reputation would continue to grow. Ten years later, the novelist Chad Harbach would comment that Wallace's effort "now looks like the central American novel of the past thirty years, a denser star for lesser planets to orbit." Wallace died in 2008.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story by D.T. Max. Copyright © 2012 by D.T. Max. Max is a staff writer at The New Yorker.

WALLACE'S GREATEST HITS

From his debut The Broom in the System to the posthumous The Pale King, Wallace gave us perfect lines.

Infinite Jest

"The thing about people who are truly and malignantly crazy: their real genius is for making the people around them think they themselves are crazy. In military science this is called Psy-Ops, for your info."

Consider the Lobster

"So then here is a question that's all but unavoidable at the World's Largest Lobster Cooker, and may arise in kitchens across the U.S. "Is it all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure?"

Girl with Curious Hair

"And he wishes, in the cold quiet of his archer's heart, that he himself could feel the intensity of their reconciliations as strongly as he feels that of their battles."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.