More than 5 percent of the world's population suffers from profound hearing loss, and about 60 percent of the deafness in infants is caused by gene mutations. That's why scientists at the Boston Children's Hospital, Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School have spent several years refining a technique to repair one of the common genetic disorders that cause deafness, offering hope to millions. The genetic disorder they repaired is Usher Syndrome.

The disorder stems from an abnormality in a gene called ush1c, which encodes the proteins in the inner-ear hair cells. These hairs convert sound vibration into electrical signals for the brain. In people with Usher Syndrome, that conversion does not happen, leaving them with devastating deafness, loss of balance and sometimes even blindness.

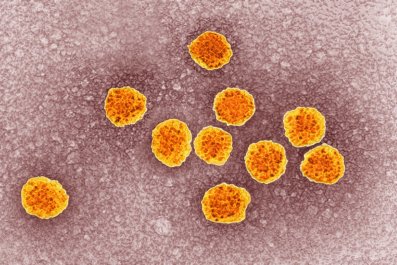

The researchers wanted to see if tackling the syndrome at its root—the abnormal gene—could reverse the damage. For this, they turned to a pioneering approach called adeno-associated viral vector, which uses a harmless virus to deliver new genes. They replaced DNA from a virus with a healthy ushc1 gene from a mouse. That altered virus was multiplied in a petri dish, then injected into the inner ears of deaf mice suffering from Usher Syndrome. After six weeks, the mice had almost perfect hearing and full recovery of sensory hair growth, brain auditory function, balance and sound sensitivity down to a whisper. (High-pitch frequency sensitivity was only partially restored.)

Dr. Margaret Kenna, a specialist in genetic hearing loss at Boston Children's Hospital who wasn't involved in this study, says that while there are devices that can bolster hearing, nothing beats nature. "Cochlear implants are great, but your own hearing is better in terms of range of frequencies, nuance for hearing voices, music and background noise, and figuring out which direction a sound is coming from." Exactly the kind of results achieved with the deaf mice.

After this study, written up in two papers published in Nature Biotechnology last February, the Boston team started preparing for human trials. In March, they exposed human outer-ear hair cells in the lab to the same ush1c-carrying virus. After 10 days, the virus penetrated about 83 percent of the targeted cells. Although cell function was not tested, the team's ability to reach so many cells has brought real hope that this technique might be able to cure not just a human ush1c gene defect but other hearing disorders caused by genetic mutations.

Brad Welling, chief of otolaryngology at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, wasn't part of that team but is cheered by their work. "The day is growing closer to human trials which will correct defects in the outer ear cells and potentially other areas of the inner ear…and we look forward with great anticipation to human application."