On a warm morning in February, as Liberia's deadly Ebola outbreak seemed to be waning, Ralph Norman was returning to his home in Paynesville—a suburb east of Monrovia—when a welder stopped him on the street and asked for help. A man, he said, was lying in his work shed, bloody and near death.

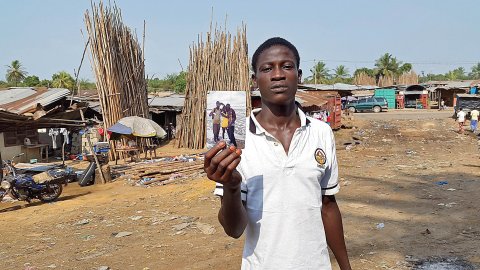

For days, Norman, a broad-shouldered middle-aged man with a boyish face, had hardly slept. He'd heard that his stepson, a troubled 21-year-old named Emmette Logan, had been in a knife fight. Logan hadn't been home since, and Norman spent days scouring the streets of Red Light, one of Paynesville's most dangerous neighborhoods, going from one drug den to another, searching for him.

Wanting to help the welder, Norman—an unemployed former soldier in the Liberian Army—rushed to the shed. When he opened the door, he saw Logan lying on his back on the sandy floor, in a pool of blood. "He was breathing just like a fish when you take it from the water," Norman said.

Norman ran from the shed and went door to door, frantically trying to borrow money for a taxi. An hour later, as he was still trying, Norman received a phone call from a friend in the military. "Your son is tango uniform," he said. He spoke in military jargon, but Norman knew what he meant: Logan was dead.

"They killed him over a golden plum," Norman later told me, using the Liberian term for a mango.

What had begun as a bloody battle over a piece of fruit would soon throw a city into crisis.

Rotting in the Darkness

In shock, Norman watched as the police quickly cordoned off the shed. Two days later, a Red Cross burial team arrived dressed in hazmat suits; a neighbor had called them, concerned that Logan may have had Ebola. The burial team took a swab of his mouth and later determined he indeed had been infected. Yet because it wasn't clear what had ultimately killed him, Ebola or his wounds, the Red Cross allowed the police to take pictures of Logan's corpse, since they would be investigating a possible murder. When they were done, the burial workers placed his body in a white bag, heaved it into the back of a pickup truck and drove to a special cemetery, where in recent months Ebola victims had been buried to prevent the disease from spreading.

Unable to afford a taxi to the cemetery, Norman and his family weren't able to attend Logan's funeral, weren't able to weep as his body was lowered into the ground. Only the gravediggers were there to say goodbye.

Back in town, as word spread that Logan had been infected with Ebola, Norman watched as health workers frantically began searching for anyone who had come in contact with him. Their biggest worry was that Logan may have passed the virus to dozens of young men from the surrounding slums—many of them drug addicts and "gronnah boys"—small-time gangsters who tend to distrust authority and thus might be difficult to quarantine. Norman also learned from Logan's friends that five young men had attacked his stepson, and that the man who allegedly wielded two razor blades was known only as Johnny. Another accomplice went by a nickname, Time Bomb—an apt metaphor for the explosive potential of the case and the disease that's recently devastated large parts of West Africa.

Over the past year, Ebola has killed more than 10,000 people. Almost half of those have died in Liberia, including 200 health workers. The Liberian government and international donors have been desperately trying to care for the sick while, at the same time, preventing the virus from spreading. They seemed to have finally won that battle: On March 5, doctors discharged what they said was the last known Ebola patient from a treatment center in Monrovia. But a new case was discovered on March 21, not long after the country reopened its borders, sparking renewed fears of contagion.

As Logan's case reveals, such fears are not unfounded. In interviews with Newsweek, Logan's friends and family, as well as health workers, police and local gangsters, recounted his last days. The story of his death and its aftermath shows how difficult it is to contain an epidemic—and solve a murder—in a country where distrust of authority is widespread and the lack of water, toilets and access to basic medical services helps the deadly virus proliferate.

Scars from the War

Logan was raised in Red Light during Liberia's bloody civil war in the 1990s. An estimated 250,000 people died in the conflict as factions, often divided along ethnic lines, vied for power. Residents named their neighborhood, a strategically important area during the fighting, after a traffic light—one of the few in the city back then.

More than 12 years have passed since the end of the war, and busy shops and market stalls now populate Red Light's crowded streets. But residents still bear scars from the war, both physical and psychological. Those who didn't fight still grew up hard and lived on the margins; they were not ex-rebels or members of pro-government militias, but they adopted many of their pernicious tactics: robbing and pillaging, fighting for stature and smoking crack and low-grade heroin, called Italian White, to get by. These people had few opportunities to escape Red Light, and many never even made it to high school.

Logan's mother worked odd jobs, cooking and selling bowls of food on the street. His biological father was a construction worker. Neither was around much, and Logan and his two older brothers, Charlie and Trokon, shuffled between the homes of friends and extended family, mostly fending for themselves. By the time he was a teenager, Logan had become a gronnah boy, spending his time jacking cellphones and car batteries to pay for food, clothes and drugs. Like most other petty criminals, Logan had multiple aliases and wore them like masks to make himself seem tough. Among them: Chance Boudreaux, the action hero played by Jean-Claude Van Damme in the 1993 film Hard Target. Logan's life, however, bore little resemblance to the glamorized violence of an American B movie. When he wasn't robbing people or getting high, Logan slept on the street, in a jail cell or in that welding shed where he bled to death.

During Logan's teenage years, after his mother had married Norman, his biological father—an addict—tried to help his sons. He sent all three boys to a Bible boot camp where organizers counseled drug-addicted teens, converted them and structured their life around prayers and chores. Logan was baptized, and for a few months, fell in love with preaching. But Logan—a tall, wiry and aggressive kid—was prone to fighting. Eventually, he and his brothers quit the program and returned to the streets. Charlie was the only one who didn't turn back to drugs.

After he left the camp, Logan began smoking more and more Italian White with his friends. He had to steal to sustain his habit, which left him at risk of being attacked, beaten and murdered. By the time he turned 21, he had a girlfriend and a 4-month-old son, but his lifestyle never changed. "He lived on the street," says Menkarweh Wonyehn, one of Logan's friends. "He was a criminal."

Wonyehn would know. Last year, the stocky 24-year-old was sleeping on the porch of his father's bar when Logan and another friend, Samuel Blama, 19, crept into his room and stole his CD player. Wonyehn went to the police, who arrested the two. Due to a lack of evidence and the pettiness of the crime, the authorities let his friends go, and Wonyehn quickly forgave them. He cared about Logan and Blama and hoped they would one day stop using drugs. He dreamed they would get clean and the three of them would start a welding business together, even though none of them had any sort of training.

Wonyehn saw what was good in Logan. In fact, Logan likely contracted Ebola through an act of kindness he showed a stranger. In January, roughly two weeks before he died, friends say Logan was walking through Red Light when he saw two men and a woman walking near a swampy patch near the road. One of the men collapsed, and Logan rushed over, picked him up, carried him to a taxi and sent the three strangers home in the cab across town. Shortly thereafter, doctors later said, the man who collapsed died of Ebola-related complications.

Logan didn't know that. Nor did he realize that he had contracted the disease himself.

Blood Gushes From His Wounds

Several days later, Logan was in Red Light, hanging out in two small tents controlled by a local drug dealer named Spoiler. A large, formidable woman in her late 30s, Spoiler once fought for the rebels. When the police would raid her yard, she sometimes confronted them topless or naked to scare them away.

One of the most popular drug spots in Red Light, Spoiler's den was where young, sinewy men hung out with girls with fake eyelashes. Most were gangsters, hustlers or prostitutes, and almost all of them were addicts. Many named themselves after rap stars—Queen Latifah, Nicki Minaj, Rick Ross and DMX. Outside the tents, potato greens and maize sprouted in a nearby garden. Inside, Spoiler's customers cooked heroin on chewing gum wrappers, then used pipes made from foil to inhale the smoke, their eyes rolling back into their heads the moment they exhaled.

Those who saw the fight between Logan and Johnny say it grew out of the latter's good fortune. Time Bomb had come into some money, about $1,000, and had given a few hundred to Johnny. Their unexpected, temporary wealth was a source of envy, particularly for Logan, and when he saw Johnny eating a mango, he began chiding him, calling it "rotten" and teasing him for burning through his cash so quickly. The argument escalated, and before long, Johnny and Logan were trading blows as the rest of the men and women in Spoiler's yard watched.

Of the two, Logan was the taller and stronger and a far better fighter, so he got the best of Johnny as they scrapped in the soft dirt. After several minutes, Johnny seemed to concede, and the two men went their separate ways. But minutes later, Logan again attacked, this time with a razor blade, slicing the smaller man's ear. As Johnny clutched his ear in pain, several of his friends, allegedly including Time Bomb, grabbed Logan, disarmed him and held him down. A few onlookers told Johnny to take Logan to the police station, but he refused. Instead, he tried to stab Logan with an old kitchen knife, but the blade was too dull and did not penetrate Logan's stomach. A friend handed Johnny two razor blades, and he sliced them across Logan's face. Then he used the razors to slash Logan's spine.

As blood gushed from Logan's wounds, his attackers fled. A bystander came to his aid, putting ground-up Christmas leaves, a local remedy, on his wounds. The next day, as the wounds festered, Logan's friends rushed him to a nearby clinic, where a nurse attended to him. He was badly maimed, and the clinic suggested he go to a hospital, but he couldn't afford it. One of the gashes on his back was deep, almost to his spinal cord. The nurse told them even a small mistake in sewing him up could have left him paralyzed.

Logan never told his family what had happened; perhaps he was too ashamed. His friends, including Blama and Wonyehn, brought him food and water as he lay in the shed. Over the next 48 hours, his condition worsened, and Blama, too, soon became ill with Ebola-like symptoms. His sister eventually took him to the clinic, leaving Logan alone in the shed.

Several days later, as word of Logan's injuries spread, Time Bomb sent money to get Logan a ride to the clinic that had first treated his wounds. Logan returned, and they re-bandaged his wounds, then took him to a hospital, where health care workers stitched him up and sent him home. They never screened him for Ebola.

The next day, February 2, a week after the attack, Logan died in the shed.

Hunting for the Virus

The news of Logan's death and the postmortem discovery of Ebola triggered alarm bells for Dr. Mosoka Fallah, a 44-year-old epidemiologist and immunologist who, over the past year, has been chasing the Ebola virus across Monrovia.

He and his colleagues were tracking an outbreak in St. Paul's Bridge, near Monrovia, where the disease had spread while many had refused to self-quarantine. (The infected man Logan had helped in Red Light, Fallah believes, came from St. Paul's.) And now the doctors feared the virus would soon spread quickly among the addicts in Spoiler's tents. "Where there has been an increase and sustained cases it has always been poor communities with low social and economic security, overpopulation and poor sanitation," Fallah says. "Early on, [the poor] decided that that was their fate, to be down, not to fight back, and…in poor communities they only trust themselves."

A few days after Logan's death, Fallah and his team traveled to the ghetto to negotiate with Spoiler about a voluntary quarantine. Fallah has worked in rough communities before, but this was his trickiest case. Since Spoiler and her cohorts are part of a drug gang, they deeply distrust the police and the government. There was also the inherent tension between the doctors trying to stop an epidemic from spreading and the police trying to solve a brutal crime. According to a source on the team that manages and monitors Ebola cases, authorities struck a deal with Spoiler: If her people agreed to be quarantined, the police would agree to stop the murder investigation. They were allegedly willing to let a brutal attack go unpunished if it meant preventing the deaths of hundreds, perhaps thousands.

Fallah declined to speak about the alleged deal, and the police did not respond to multiple requests for comment. But once the dozens of young men who may have had contact with Logan agreed to be quarantined, the investigation stopped. And, almost three weeks later, when the Ebola team finally caught up with Time Bomb and few other suspects, none were arrested. The nurses who cleaned and bandaged Logan's wounds were also quarantined. The hospital worker who stitched him up later died of the virus in a treatment unit. The only person who remained at large was Johnny, the prime suspect in the crime and someone clearly at risk for infection. His mother said she didn't know where he was. His friends suspected he didn't believe the police would honor their part of the deal and he had gone into hiding. Rumors swirled that he had fled to Sierra Leone. But no one really knew if he was dead or alive, or if he had the virus, which was likely.

While Fallah knew finding Johnny was crucial, he had to also make sure the young men in Spoiler's yard stayed in an Ebola treatment center until it was clear they weren't infected. For the next 21 days, these young men lived well under his watch. The doctors paid them $10 a day, provided them with clothes, fed them chicken shawarma and soda and gave them access to satellite television—luxuries in a country where the average person survives on less than a dollar a day. According to workers in the unit and the men under quarantine, the Ebola treatment unit even gave many of the gronnah boys a low dose of heroin and marijuana to keep them from escaping and spreading the virus. All the while, the Ebola team, fearing a scandal, tried to keep news of this unusual arrangement away from the press.

Three weeks later, the 32 gronnah boys lined up at the exit of the treatment center dressed in clean T-shirts with logos that read, "Goodbye to Ebola." They were all healthy. No one, save for Logan, the health care worker who stitched him up and Blama had been infected. (Remarkably, after weeks of treatment, Blama survived and left the hospital, vowing to stay off drugs.) As they filed out of the treatment center and onto a bus, many chanted in unison: "Who let the dogs out? Who! Who!" And as they were zoomed across town on a bus, the men sang church songs as bystanders gawked. When they stepped off the bus in Red Light, Fallah handed each $50, a bag of rice, some beans and cooking oil.

'That Man Laying Down There'

Roughly two months have passed since Logan's death, and Liberia's Ebola epidemic seems to be under control. But Norman is still trying to make sense of what happened to his stepson. He's glad the virus spread to only a few other people, but Johnny remains at large, unprosecuted and, more important, untested. The authorities no longer seem to be looking for him.

On a recent afternoon, Norman was finally able to visit the cemetery where Logan is buried. Located 45 minutes outside of Monrovia, in an area known as Disco Hill, Logan's grave is a large clay mound marked with a white wooden cross. On the back of the cross, his name and the day he died, February 2, 2015, are written in black marker.

"That man laying down there..." Norman said to himself. He voice trailed off, and he began to weep. As he cried, the wind blew, rustling the trees around the gravesite. Through his tears, Norman stared at the cross. Then he turned away.