You may think you know the desert. Sand and cacti, spread over an expanse of infinite flatness, baked by relentless sunlight. Roadrunners chased by wily coyotes. Rattlesnakes lurking under rocks. And meth labs, just as in Breaking Bad. Meth labs guarded by rattlesnakes.

If this is your conception of the desert, then you are clearly not familiar with the oeuvre of Death Valley Jim, an explorer, writer and activist who knows the California desert as well as anyone alive. His is a particular kind of knowledge: ghost towns, abandoned mines, the vestiges of Native American villages, the humble graves of unlucky prospectors. He knows about the desert tortoise, sure enough, but also about the legend of Yucca Man; about the effects of prolonged drought on desert succulents but also about the Spanish galleon that sank near what is today the malodorous Salton Sea.

Don't get too excited. Like so much else in the desert, that colonial treasure could be a mirage. But if does exist, Death Valley Jim knows the guy who might know where it is: He interviewed said guy on his radio program (did I forget to mention that, until recently, he was also a radio host?). His is the desert visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists each year, as well as the desert of hardy desperadoes with names like Seldom Seen Slim, a place precious and rough, with wildflowers and mine shafts.

In an age of "glamping" and virtual vacations, Death Valley Jim—his real name is Jim Mattern, but he never uses it—makes the case for the desert as a place of sacred mystery, a place that might kill you or, if you're willing to give yourself over to the blazing expanses, might turn you into a more reflective, thoughtful human being, one who is aware of a world beyond the glowing confines of an iPhone screen.

And then maybe kill you.

They Paid for Their Mistake

Augustinus Van Hove and Helena Nuellett had a mission: find the famous Joshua tree that graces the cover of U2's Joshua Tree album. The two European tourists had recently arrived in Los Angeles, and after a short stay there and in San Diego, they drove east into the desert. On August 22, 2011, they set out into Joshua Tree National Park, famous for the spiky, spindly trees that look like they were cultivated on some other planet before a seedling floated to Earth. The Joshua tree captured by Anton Corbijn for U2 was not in the national park that bears its name, but the two tourists did not appear to know that.

Van Hove and Nuellett drove their rented Dodge Charger off a main park thoroughfare and onto Black Eagle Mine Road, according to a reconstruction of events in The Desert Sun newspaper. Their car, said the Sun, became stuck in a wash, "and they couldn't get it out. There was nowhere to rest in the shade," so they set out for the main road, which was about 8 miles away. In ordinary circumstances, this might pass for a decent day hike. In 108-degree heat, it meant death. Another tourist later that day discovered their bodies.

"The desert will kill you," Death Valley Jim says bluntly. It is not likely to kill him, though, and that has as much to do with his truck as with his desert survival skills. Jacked up on tires that look like they were stolen from a Boeing 747, his beloved 2013 Jeep Wrangler is what the steed Rocinante was to Don Quixote, a trusty conveyor through surreal realms.

"I might be able to pull it off," Jim said to me on a recent winter afternoon as he tried to turn his Jeep around on an especially narrow section of Black Eagle Mine Road, just a mile or two from where Van Hove and Nuellett died. We had just stood looking at the remnants of the Eagle Mountain mine, which some wanted to turn into a garbage dump (horrible idea, according to Death Valley Jim) or, when that push failed, a hydroelectric plant (less horrible, but still pretty terrible). Below us was a dry gulch, and while the drop was only a dozen feet or so, the boulders down there looked like the misshapen teeth of a monstrous jaw. As ever, the desert was going to allow little room for error. Which, frankly, is thrilling in a world where so many of our thrills involve clicking and swiping. Death Valley Jim drove his Jeep to the precipice, then up the opposing slope. It lurched, huffed, tilted, but, like a mountain goat, it never lost its footing. Soon we were cruising down the park's main road again.

Danger is one of the desert's allures, the price it extracts for all that unperturbed open space. It's like a meditation retreat without the sanctimony, a mindfulness exercise where your guide to the sublime is a salamander skittering between sun-blasted rocks, a place whose utter lack of wireless service is one of its best features. "The desert reduces one to a rawboned simplicity," wrote the theologian Belden Lane in The Solace of Fierce Landscapes. "Life out there is lawless. The structured patterns of civilization do not extend that far. Law and order break down."

Bernie Sanders and Whiskey

Death Valley Jim does not look like the desert guide you've probably pictured. You are more likely to find him wearing a hoodie than a Patagonia hardshell. Nor is he an advertisement for Whole Foods, with his predilection for menthol cigarettes and fast-food burgers. His stringy blond goatee makes him look Amish, except that Death Valley Jim is not especially pious. On one side of his neck is a tattoo that says, "Live fast," and on the other is a tattoo that says, "Die young." He has a 9/11 tattoo, though he has no personal connection to the attacks. There are other tattoos too, all of which he says he regrets. He also has a septum ring, which he does not regret.

"My dad hated children," he tells me. Mattern père was in the Air Force, a technician who worked on the Titan II missile. He moved his wife and child to California, Arizona and Arkansas. Death Valley Jim's parents split when he was 13, and he returned to central Pennsylvania with his mother. They lived near Matternville, which he says was founded by his ancestors.

Death Valley Jim says he was "a punk-rock kid." He dropped out of school in the ninth grade, wanting to escape the booze and weed that were consuming him more rapidly than he was consuming them. He moved out of his mother's house and began to work as a promoter and manager in the local punk scene.

He met his wife in 1998. Together, they started a record label, Open Grave, that represented bands with names like Atrocity and Demon Dog Sperm. They stayed in Pennsylvania for a while, but Death Valley Jim's father, having retired from the Air Force, moved to California City, California. In the late aughts, they moved in with him.

Despite its ecumenical name, California City is a sparsely populated town about two hours northeast of Los Angeles, in the high desert of the Antelope Valley. Incorporated in 1965, it was supposed to be the next great metropolis wrested from the arid land. Today, it is home to 13,000 people, known to the outside world mostly through avid explorations by the lovers of emptiness and ruin, both of which California City offers in ample quantities. But it is also a perfect place from which to venture into the desert, for the barriers between human and natural life have largely collapsed in California City. The desert eternally beckons and intrudes.

The Matterns, who eventually tired of running a record label, were taking frequent trips to the desert. To keep his family back East abreast of their travels, Jim started posting photos online. He soon noticed, though, that his blog was attracting the interest of other desert lovers. So he kept exploring and kept putting the record of his explorations online, while also following new "leads" sent to him by fellow desert denizens.

It has been about five years since Death Valley Jim published his first guidebook; 10 more have followed, covering the Death Valley and Joshua Tree national parks, as well as other parts of the California desert. When not exploring or writing about his explorations, he leads guided tours for clients—foreigners, photographers, city-slicker journalists—who want to ditch the paths delineated by Lonely Planet and see the desert as he knows it.

If Death Valley Jim has interests outside the desert, I remain unaware of them. He does not regularly watch television. His reading material is primarily archaeological papers from obscure magazines that do not exist outside of college libraries. He also likes Bernie Sanders and whiskey. "I get bored too easily," Death Valley Jim says. I point out the irony of that declaration, since for most people, boredom is the desert's prevailing quality. Death Valley Jim does not appear to agree. The desert is the thing that entrances him, that keeps him sane.

Malevolent Bouncing

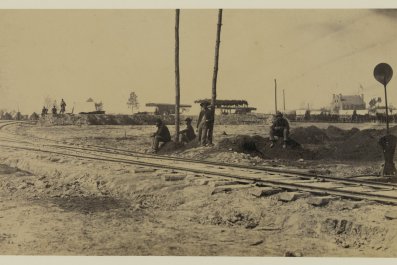

William "Burro" Schmidt was a man of exceptional purpose, but a purpose utterly without a point. Schmidt spent 36 years, from 1902 until 1938, boring a tunnel through a remote section of the already remote El Paso Mountains. He worked alone, his only companions a pair of donkeys. The aim was presumably to facilitate the transportation of ore. In 1920, a new road rendered the shortcut unnecessary, but Schmidt kept blasting through the granite. "Driven to complete his monumental one-man project, Schmidt simply disdained precious metals," wrote Scott Schwartz of DesertUSA, even though plenty of precious metal may have been within his reach, if he'd only bothered to look for it. He didn't. He did finish the tunnel, a half-mile passage through darkness into nothingness. He died in 1954, no wealthier than when he first came to the desert in search of wealth.

Donald Trump might not approve of Schmidt's money-making instincts, yet there seems to me something fundamentally American about his will, at once admirable and disturbing. Can any of today's social scientists point to a finer example of pure grit?

It was inevitable that, in my research into Schmidt, I came across Death Valley Jim. He had written about Schmidt's tunnel, of course. And about the Pleasant Valley petroglyphs of Joshua Tree ("created during a state of altered consciousness"). And about the Queen of Sheba mine in Death Valley ("a picturesque ore chute extends from the cut in the mountain").

I first went trekking with Death Valley Jim and another explorer, Dusty House—Angeline Duran Piotrowski, a hiking guide from Los Angeles—through the El Paso range this past fall, a few months after learning about his work. We had met in Ridgecrest, a town at the edge of Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake and, from there, drove into progressively more rugged land. The roads were unpaved, yet Death Valley Jim plowed forth with relish. At one point, Dusty House shouted that she was afraid she would die from the truck's malevolent bouncing. Jim slowed down slightly.

El Niño had not yet arrived in Southern California, and the foothills were ochre swells upon the land: featureless, endless. But to the expert, they are neither. Death Valley Jim parked, and we climbed a hill thick with twisting creosote bushes. About halfway up the slope, Death Valley Jim stopped and pointed at some rocks. We were standing in what remained of the Coso village of Terese.

Nothing marks off Terese from the rest of the desert: no signage, no fencing, no kitschy explanatory panels from the 1970s. Nothing significant marks it in literature either, according to Jim, except for a few references in obscure scholarly studies. Perhaps only a few dozen people have ever seen the village since the Coso—or the Kawaiisu, who also lived in this area—departed from here, which may have been more than a thousand years ago.

The site is a wonderland of petroglyphs, white etchings on black rock: bighorn sheep, human figures, spindly rays of sunlight. "These are the tweets of the past," Death Valley Jim says as we walk through the village, warning me not to touch any of the petroglyphs. We stand in a circular arrangement of rocks that once served as the foundation for a wickiup, a sort of domed hut made out of branches. He also shows me what looks like an ancient pestle. We are careful to leave the site undisturbed.

Warnings about respecting cultural sites (as well as natural ones) appear frequently in his books, but they won't pacify detractors who say Death Valley Jim is inviting looters and vandals into those parts of the desert where their transgressions are least likely to be found. The superintendents of both Death Valley and Joshua Tree have voiced disapproval of Jim's work. It's easy to dismiss them as joyless federal bureaucrats, but looting of abandoned mines has become so frequent in Joshua Tree that two sites were recently closed.

Native leaders worry about burial sites, about tribal artifacts ending up in some boho Santa Fe antique shop. "I wonder what society would think if a group of Natives went to a cemetery and starting digging up Civil War vets," says George Gholson, chairman of the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe in Death Valley, adding that Death Valley Jim "should consult tribes in the area." Jim says he has tried, to no avail. He also claims that the National Park Service has discouraged the sale of his books and that its rangers have tried to intimidate him (David Smith, the superintendent of Joshua Tree, says his agency is "relatively careful about not interfering with the marketplace"). "They see me as an outlaw," he says proudly. There is little repentance: He thinks public lands should have few restrictions. "That land is set aside for the people of this country."

Though Death Valley Jim fervently defends his own use of the desert, he just as fervently derides off-roaders, renewable energy evangelists and others who fail to appreciate the desert as deeply as he does. "I hate man's footprint," he says. It is a hot desert afternoon in late fall. Nothing moves. The desert seems immutable, the thing that it has always been and always will be. The rattlesnake sleeps. The tortoise hides. Life awaits evening.

"Yet here you are," Dusty House says.

Thousands of Birds Cooked

Last spring, Death Valley Jim posted an item on his blog titled "Earth Day Is Stupid." This was not an expression of current beliefs but, rather, an acknowledgement that he arrived at activism on the long road. "I didn't honestly give much of a shit about the environment," he wrote of his salad days in that post. "I littered, used a ton of aerosol hairspray to hold up my mohawk, and I despised the Grateful Dead and drum circles (I still feel the same way about the Grateful Dead and drum circles)."

Jim was inspired to be more of an activist by Chris Clarke, a shaggy fellow resident of Joshua Tree who is the environmental editor at KCET, a public television station in Southern California. Clarke taught Death Valley Jim that to love the desert is to fight for it, especially since, in recent years, the California desert has attracted newfound, unwelcome interest.

The desert, always hot, is getting hotter, as vulnerable to climate change as any other ecosystem on the planet. Rising temperatures in deserts like the Mojave threaten the plants and animals that have learned to live there. The recent California drought has only further desiccated an already desiccated place.

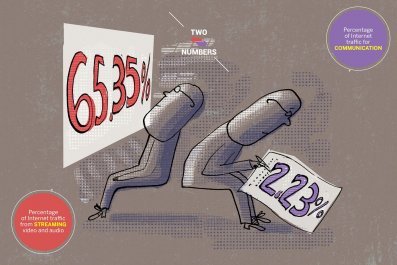

One way to stop climate change is to reduce carbon emissions. Pretty much everyone—well, everyone who isn't hoping to become the Republican nominee for president—agrees that fossil fuels are the main culprit in this ecological crime. To sever our reliance on oil, coal and gas, we need to find alternative sources of energy. One especially promising renewable source of energy is the sun.

You probably see where I am going with this. One estimate holds that the Earth's deserts receive enough sun in just six hours to easily power the entire world for an entire year. Putting solar panels in deserts like the Mojave would seemingly solve our energy needs. By killing the desert, we save those parts of the world that are not desert.

The battle over solar energy is really a battle of competing visions of what it means to be green. Are we fighting to preserve the cottontop cactus, or are we fighting to keep the polar ice caps from melting? Is there a way to fight for both? The question may be moot, for both the federal government and the state of California have been aggressively promoting utility-scale solar and wind projects in the desert with, among other incentives, an estimated $51 billion allotment in President Barack Obama's 2009 stimulus package.

What is wrong with utility-scale solar projects? Detractors inevitably reply with a single word: Ivanpah. At 5 square miles, the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility outside of Las Vegas is the largest solar array in the world. It is composed of three fields of mirrors, each a vast and crystalline lake. The mirrors, or heliostats, focus the sun's rays and boil water, which rotates turbines as any other electrical plant does. But the plant is inefficient and must burn natural gas to function. That released 46,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere during Ivanpah's first year of operation.

As far as desert life is concerned, Ivanpah is a real disruptor, and not the kind Silicon Valley likes to crow about. While the plant was being built, its developers had to relocate some 200 desert tortoises, at a cost of $55,000 per reptile. Once the plan went into operation, its heat rays cooked thousands of birds per year, leading one wit to condense Ivanpah's travails into a bumper sticker: "This electric vehicle is powered by coal and dead birds."

Proponents of solar energy argue that arrays are becoming more efficient, that the industry has absorbed the tough lessons of Ivanpah. But no innovation is going to make it possible for solar arrays to be anything but glassy invaders of open country. Moreover, research by Michael Allen, G. Darrel Jenerette and Louis Santiago of the University of California, Riverside, strongly suggests that clearing the desert floor exposes a type of sediment called caliche, which in turn releases carbon dioxide into the air. That would make solar arrays emitters of the very pollutant green energy is supposed to keep out of the atmosphere. There's surely a droll bumper sticker in that too.

According to the Bureau of Land Management, which administers public lands across the nation, there are eight solar projects "in various stages of development" and five additional "pending solar applications" in California. California's governor, Jerry Brown, wants the state to get half of its energy from renewables by 2030. Unless someone finds a way to harness electricity from Kanye West's frequent Twitter rants, solar is going to be a major factor in that push.

Desert rats with an activist bent, like Death Valley Jim, see the Bay Area about as favorably as do the Jerry Falwells of this world, though for different reasons. Many solar and wind energy companies are based in San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley, places that can come across as self-satisfied enclaves of green living: the electric car, the locavore restaurant, the gray-water garden. But while San Francisco's enlightened classes badly want to keep Lake Tahoe blue and the redwood forests green, they care little about the desert, charge some. If the desert suffers for their vision of sustainable living, so be it. Nobody lives there, anyway. Nobody cares.

So who is keeping the desert from becoming one giant solar panel? Who is fighting the good fight on behalf of the desert tortoise, which knows nothing about rising ocean levels and depleted ozone layers? An octogenarian liberal Jew from San Francisco.

Dianne Feinstein is very much of San Francisco. She served as its mayor before becoming a United States senator, a position she holds today. But despite her Northern California origins, she is a lover and defender of the desert. Talking on the phone from Washington, Feinstein tells me she first ventured to the California desert in the 1960s, at the behest of Governor Pat Brown (Jerry's father), who wanted her to investigate the terms of parole at a women's prison east of Los Angeles. After work, she would spend the weekends in the desert with her husband Bert. The surreal landscape of the Mojave enchanted her. "Color in the desert is amazing," she says. "How the sky looks, how the shadows fall."

Feinstein's love affair with the desert resulted in the California Desert Protection Act of 1994, which sanctified Joshua Tree and Death Valley as national parks while also creating the Mojave National Preserve. But by the late aughts, Feinstein saw large stretches of the Mojave fall to energy speculators, turning the desert into what she calls a "checkerboarded" landscape.

In 2010, she introduced a new California Desert Protection Act, but in a Congress that can barely agree on the days of the week, the legislation languished. So she turned to President Obama, asking him to use the 1906 Antiquities Act to create three national monuments—Sand to Snow, Castle Mountains and Mojave Trails—that would keep 1.4 million acres of desert as pristine natural space.

In February, Obama did Feinstein one better, setting aside 1.8 million acres as part of the three national monuments she requested. The San Francisco Chronicle noted that this amounted to one of "the largest continental monument designations in recent times" while elevating its hometown senator to the rank of "California's great conservationists." Death Valley Jim was just as effusive: "Senator Feinstein has singlehandedly done more to protect the California desert than anybody else in the past quarter of a century," he says in an email.

Feinstein is no idealist, and she understands that stunting solar's growth would be a Pyrrhic victory. But, she argues, "there's no problem finding places" for large renewable energy projects. Like those in Death Valley Jim's dusty band of rogues, she believes solar arrays belong on "distressed" lands like brownfields and unused farms. Solar shades on parking lots, solar roofs on warehouses. Anywhere but the desert, which cannot be reclaimed once surrendered. "You have the privacy," she says. "You have the beauty of unfiltered light. You have just beautiful country."

Parched Gentrification

Death Valley Jim lives in Joshua Tree, a small town near the entrance to the park. It has a cheerful, bohemian vibe, whereas some other nearby hamlets either cater to the military or not to anyone at all. I had dinner one night at the Joshua Tree Saloon with Jim, Chris Clarke of KCET and another activist, Seth Shteir of the National Parks Conservation Association. The bar was filled with young people who could have been airlifted from the hippest precincts of America: Silver Lake, the Mission District, Bushwick.

"The Mojave is being slowly gentrified," says Clarke. This is true in ways both large and small. Joshua Tree has been fighting the arrival of a Dollar General store, and though this might seem like a minor squabble, it is no different from New York City's long-standing efforts to keep out Wal-Mart, a fight less about retail than cultural values.

The gentrification in the Mojave may look different than it does in East Los Angeles, but it is just as inevitable. Palm Springs, that faded mid-century oasis, is resplendent once again, with an Ace Hotel to sate the crowds from Los Angeles and bestow the kind of cachet most American cities would sacrifice a deputy mayor to acquire. It's only a matter of time before Palm Springs is declared "over" and the cool kids migrate elsewhere: Indio, Indian Wells, maybe even Barstow. Well, probably not Barstow.

"Every asshole here has a swimming pool," Death Valley Jim said on an afternoon last January as we drove south and east from Joshua Tree, into freakishly green valleys whose hostility to human life we had conquered, and lavishly so. The outposts here have uniformly blissful names: Palm Springs, of course, but also Rancho Mirage and Palm Desert. Thousand Palms, Bermuda Dunes. A proposed 8,500-unit development has been branded Paradise Valley.

The golf courses here are so numerous that some have thought Obama may move to Rancho Mirage when his term is through, spending retirement on a sport made for senescence. He was there recently, to host Asian leaders at Sunnylands, the sumptuous modernist estate known as "the Camp David of the West." Sunnylands was a favorite of Republicans, including Richard Nixon, who created the Environmental Protection Agency, and his successor Gerald Ford, who is the only president to have ever served as a park ranger (Yellowstone, the summer of '36). Built by publishing magnate Walter Annenberg, Sunnylands evokes a cool mid-century confidence about the American project. It is one thing to discover an oasis, but another thing altogether to build one out of nothing, to fashion a Xanadu from the most inhospitable terrain imaginable. In the end, a golf course in the desert may be the pinnacle of human achievement.

Assaulted Sea

On one end of the spectrum of ways to treat the desert is Joshua Tree National Park. That is, fence it off and don't use it at all, ever: the desert as museum. On the other end, we have utter ruin, horrific abuse, the desert as palimpsest for humanity's grossest impulses. We have the Salton Sea.

If parks like Death Valley and Joshua Tree are the desert untouched, if solar farms like Ivanpah are the desert harvested, and towns like Palm Springs the desert tamed, then the Salton Sea is the desert molested.

"This place is spooky," Death Valley Jim said as we pushed past Palm Springs, through heat and haze of a desert afternoon, toward the pungent body of water that is California's biggest lake, created when the Colorado River overflowed in 1905, settling in a depression more than 200 feet below sea level. Thus was born the 380-square-mile body of water known as the Salton Sea, nurtured by agricultural runoff from the farms of the Imperial Valley. It may be the most unnatural place in the world.

It wasn't always this way.

The Salton Sea was once a famous resort, a waterfront paradise where you might have spotted the Beach Boys or Frank Sinatra. But the same forces that created the Salton Sea doomed it, the water becoming increasingly saline and fetid. The stars left; the motels closed; the fish died. They continue to die routinely, their corpses littering the shore, creating a stench that is hard to describe and harder to stomach.

"How do you save a place that's so far gone?" Death Valley Jim wondered as we walked through some of the blasted communities that front the lake. Though people still live here, the living seem to be a distinct minority in the Salton Sea. Everything is abandoned, covered in graffiti, caked in salt. I will never eat tilapia again.

The Dutch masters painted still lifes of sumptuous spreads to remind the viewer of mortality: Just as this bunch of grapes will wither, so will you die. Walking the shores of the Salton Sea put me in the same morbid frame of mind. Here were the "things rank and gross in nature" that Hamlet bemoaned. There are now efforts to save the Salton Sea— Jerry Brown has allocated $80 million for that effort—because its drying-out could spread toxic dust, and because its southern shore is an important bird sanctuary (and the only section that doesn't look like an utter hellscape). But there is a despair blowing off the sea that nothing will diminish, a ruin irrevocable. And everyone knows it, Death Valley Jim most of all. Every new development could turn the California desert into some nightmarish simulacrum of the Salton Sea.

Somewhere between the Salton Sea and Joshua Tree is a large wind farm, the turbines rising like blanched tree stumps from the hillsides. Do projects like this help preserve the natural environment, or do they bring the natural environment ever closer to ruin and, what's more, do it under a beneficent guise of green? I wasn't sure. Death Valley Jim was.

"Fucking hideous," he said.