This story originally appeared on Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

"It was my daddy who tamed the dinosaurs," the proud daughter of the hero of Deepwater Horizon foreshadows, as her father Mike Williams (Mark Wahlberg) leaves for his job as chief electronics technician on the doomed rig. As viewers, we already know that those "dinosaurs" that have been compacted over millennia into oil don't plan to stay tame. The movie, directed by Peter Berg, is a satisfying action spectacle and an emotional tribute to the 11 men who died aboard the Horizon when the Macondo well exploded on April 20, 2010. It's also a bit of an anti-corporate fable. Is it too much to expect that the film might also make us think a little about what the Horizon blowout did to the Gulf —and the responsibility we all, as consumers of oil, bear for that destruction? Maybe so.

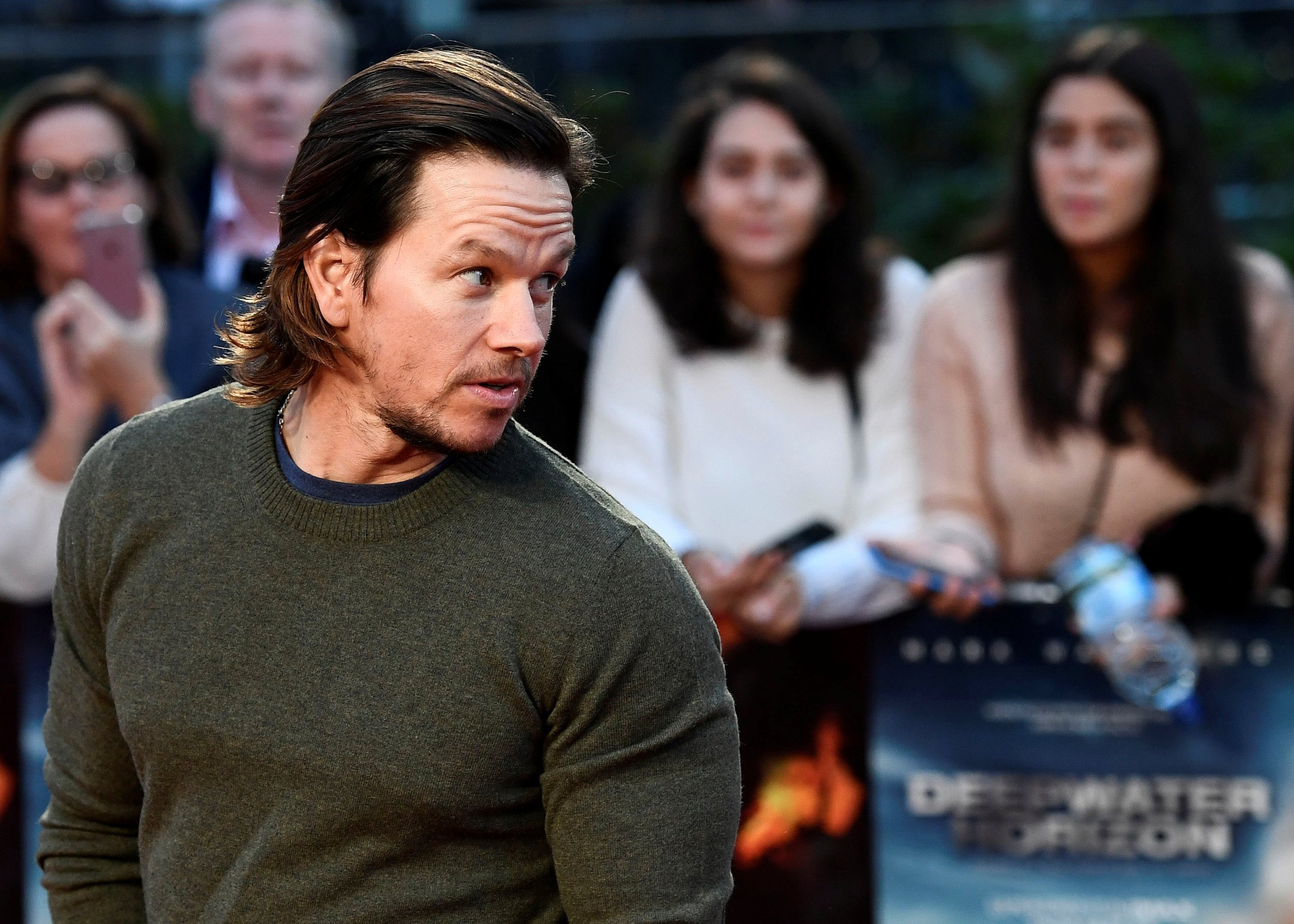

The film's narrative bones come from a 2010 New York Times tick-tock by David Barstow, David Rohde and Stephanie Saul. Like Berg and Wahlberg's previous collaboration, Lone Survivor, Deepwater Horizon is about tough guys doing competent things in the throes of chaos. Wahlberg's Williams is a former Marine and devoted family man; Kurt Russell's Jimmy Harrell, the head of the crew working the rig, is tough but fair, a father figure beloved by his crew members; Andrea Fleytas, a bridge officer played by Gina Rodriguez, is a beautiful, plucky tomboy, with a smooth ponytail and an interest in engine repair.

In the stage-setting portion of the movie, Williams, Harrell, and Fleytas settle in for their three-week tour of duty on the rig. As they do, they uncover a series of ominous signs that safety procedures are not unfolding as they should. A group of visiting BP executives—headed up by Donald Vidrine, played by John Malkovich, wielding a comically heavy South Louisiana accent—turns out to be venal to the core, worried about delays in drilling, even while the crew presents them with evidence of neglected maintenance on the rig. Mr. Jimmy (as his crew calls him) isn't afraid to speak truth to power. "You're a $180 billion-company, and you're cheap," Mr. Jimmy scolds Vidrine. As problems start to mount, and the well eventually explodes, this "cheapness" is the clear villain.

The heroes are the crew members, who struggle through the flaming debris of the rig to hold the damage to a minimum, and—that failing—rescue their colleagues. As the disaster unfolds, it's a little hard to see what's going on—everyone is covered in oil, mud, and blood and flaming pieces of steel fall all over your field of vision. But, like the survivors, you stagger through the story holding onto Wahlberg's steady, commonsensical Mike Williams, who's the one to calm everyone else down and keep them from cutting the line for the lifeboats. Mr. Jimmy staggers around the rig on lacerated feet, barely able to see, but still determined to take command; the handsome young floorhand Caleb "Hollywood" Holloway (Dylan O'Brien) throws himself into the breach over and over again.

Barstow, Rohde and Saul's reporting for the Times is laced through with anecdotes about uncertain and unheroic actions taken by certain members of the crew. This wasn't because people weren't brave, Barstow said in a 2010 interview with Democracy Now. Transocean, the company that owned the Deepwater Horizon, gave crew members who were training in safety procedures "very big, thick guidelines," Barstow said.

"But there was a kind of contradiction in these policies. The policies would say, 'You really need to act quickly. It's crucial.' … And yet, they would also say, 'But there's a really big danger if you overreact. And if you overreact, then it could cost us a lot of money, it could create other safety issues.' And you see moments along the way where that contradiction essentially froze key people at key times."

There's a bit of this freezing on display, but the film centers on the conflict between the right-thinking crew members and the greedy BP execs. The kind of bred-in uncertainty Barstow points to is difficult to convey on film, but it's much more revealing about the way corporate objectives work against each other to create dangerous conditions than simple execs-versus-grunts rabble-rousing.

The damage to the Gulf is a shadow presence in this film, personified only by an oil-covered pelican that appears, thrashing wildly, in the cabin of a nearby boat as the disaster unfolds. Interviewed recently by the Times, the real-life Mike Williams said that the victims' families had long been upset by what they see as an excessive focus on the environmental effects of the spill. "We understand the oil. It's bad, yes," Williams told the Times. "The birds are dying and the shrimp and the crabs and all that stuff. But those aren't brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, sons, daughters. Shrimp can come back. People, you can't bring those guys back."

But surely it's possible to have feeling for these human losses, while still believing that what happened to the Gulf deserves consideration. In the century-plus of resource extraction that has brought us to our current climate tipping point, you can find many such episodes of human tragedy: the Senghenydd pit disaster, which killed 439 coal miners in Wales in 1913; the Lac-Mégantic oil transport train derailment,which took the lives of 47 in Quebec in 2013. I hope it doesn't take away from the grief of any of the families who were affected to argue that these periodic acute disasters are epiphenomena, compared with the bigger story of environmental degradation and loss in modern times, which threatens life on Earth as we know it.

I wish there were a way to tell both tales at once. Big movies like Deepwater Horizon are way better at showing the heroism and sacrifice of individual humans than pondering the kind of damage this disaster did to the Gulf—never mind the kind of existential damage oil is doing to us all. I left the film moved to tears, and still feeling like something huge was missing.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.