For a "dead" consensus, traditional conservative fusionism sure looks healthy, doesn't it? I can only hope that, when my time comes, I look as fresh in the grave.

Insofar as it represents anything more than a post hoc rationalization for President Donald Trump's caprice, the postmortem for the pre-2015 Republican Party reads as follows. By the 1980s, a set of serious problems had arrived in the United States. Thankfully, President Ronald Reagan and his fellow travelers had good answers to these problems and, by and large, they managed to solve them. But, having done so, the Republican Party and its friends within the institutionalized conservative movement failed to move on. Instead, they decided that the platform of 1980 was immutably true and necessary, and that it was applicable to all places and all times. And so, in 2015, the party rebelled and nominated a politician who saw things differently. That politician, Donald Trump, managed to win the nomination, ascend to the presidency and recast the movement in his image. These changes are likely to be permanent. R.I.P., Reagan. Long live Trump! Amen.

Like Tom Sawyer watching his own funeral, I must express some skepticism here. It is certainly true that the Republican Party sometimes falls back on gauzy nostalgia. It is true, too, that there seems to be no problem with which the United States can be confronted that does not lead to prominent figures within the GOP calling for a tax cut. But—and this is the key point—I can see no evidence either that these habits are on its way out, or that Donald Trump's arrival into the firmament did anything much to limit them.

Indeed, I cannot stress enough how bizarre it would be to point to Donald Trump as evidence that the GOP has changed meaningfully on policy, given that the standout achievements of Trump's presidency—the ones to which Trump and his defenders themselves point with pride—are a massive tax cut inspired by former House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI); the stocking of the federal judiciary with originalist judges, selected with the counsel of the Federalist Society; an attempt to repeal Obamacare that was ultimately killed not by the president, but by the late Senator John McCain (R-AZ); an all-of-the-above pro-life agenda; widespread, executive-led regulatory relief; the moving of the Israeli embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem; the tearing up of the Iran nuclear deal; and a criminal justice reform bill that, while laudable, flew directly in the face of almost everything Donald Trump has ever said on the matter and was opposed by almost everybody who is currently touting a new approach to conservatism.

Think back to 2015 and ask yourself whether the presidency we just lived through was what you imagined it would be? Did you expect Donald Trump would wait until the Republicans had lost control of the House of Representatives to try to build his wall? Did you expect him to talk as much as he did about the stock market and the profits of large corporations? Did you expect he and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) to find so few areas of policy disagreement? I didn't.

Certainly, the Republicans under Trump failed to take federal spending seriously, or to do anything of consequence to deal with our out-of-control entitlement spending. But how, exactly, did that differ from last time they controlled all of Washington? And, frankly, how did it differ from the Reagan administration? This is what Republicans do: They talk a great deal about the debt when a Democrat is in the White House, and they ignore it when their own guy is president. The one area in which President Trump differed from most other Republicans was in the area of trade. But, even there, Trump's actions were haphazard, half-hearted and, because they were not put before Congress, unable to survive contact with the next president who happens to disagree.

All told, this was a fairly standard record, which would not have looked that much different had it been assembled by President Mitt Romney.

Which is to say: Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. On almost every question outside of his behavior, Trump really was la même chose. And why wouldn't he have been, given that the evidence against the "zombie consensus" is so weak?

Or, often, non-existent. I am genuinely tired of being told by populists that the United States as it currently exists is some sort of libertarian paradise in which free market fundamentalists have won every battle and shrunk the government down to a nub at the expense of the downtrodden and frostbitten. They—we—have not. Sure, free market types have won a number of important policy battles over the last century—none of which, it must be said, were opposed by President Trump or his ideological allies. (And, given how rich and peaceful America is, everyone should be thankful for that.) But we have not managed to retrench the state in anything like the way we would have hoped to, and we have not entirely rejected the notion of the "common good." Inasmuch as the criticism of the status quo is that it is in some way "extreme," that criticism is worth ignoring.

What is worth engaging with is the attendant charge that, irrespective of its merits, the traditional conservative offering has ceased to reflect the concerns of a majority—and, in a democracy, that itself matters. Here, the reformers do have a point, although it is not an especially strong one, all things considered. It is true, of course, that since 1988 the Republican Party has won the "popular vote" in a presidential election only once—and that, even when it did win, in 2004, it did so narrowly. But it is not at all clear that this is the only, or even the best, way of judging the popularity of the fusionist cause. The most obvious problem, of course, is that this argument focuses on the presidency at the expense of everything else, and, in so doing, misses the remarkable success that traditional Republicans have had at literally every other level—success, it must be said, that has been spearheaded by a cast of "generic Republican" candidates who have talked incessantly about exactly the sort of things that are supposedly no longer of interest to the masses.

Since they took the House of Representatives in 1994, Republicans have controlled it for all but six years. Since they took the Senate in the same year, they have controlled it for all but nine. And, since 2006, 45 states have elected a Republican governor to at least one term. Not bad for an out-of-touch party that nobody likes! Look at the two most impressive and sustained models of "red state" governance in the nation—Texas and Florida—and you will see that they are the result of the same policy priorities that have animated Republicans for decades: low taxes; responsible spending; suspicion of entitlements and unfunded liabilities; a healthy business environment; opposition to gun control; support for charter schools; a preference for originalist and textualist judges; disdain for socialism; and the assimilation rather than rejection of legal immigrants. Even the "Tea Party" movement, a populist uprising of 2009 and 2010, was traditional in nature. In tone, the Tea Party movement was anti-elite, yes. But what did its adherents want? And how did it differ from what, say, the Chamber of Commerce wanted?

The truth is that the fusionist project is alive and well, and it will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. The center of gravity within the Republican coalition will shift around, as different issues drive attentions and different political figures come and go. And if, as seems likely, conservatives talk themselves into regulating Silicon Valley in the hope that it will be nicer to them, some members within that coalition may have to learn a few hard lessons about government power all over again.

But, as a general matter, there has been no great overhaul of American conservatism with which we must contend. That a figure as mercurial as Donald Trump was pushed so quickly into the longstanding policy mold should provide as good a piece of evidence for this as we are likely to come by in this life or the next. So we'll talk, and we'll talk, and we'll talk, and we'll be briefly seduced by the new and the upside-down—and, eventually we'll be reminded that politics is what happens to you while you're busy making other plans.

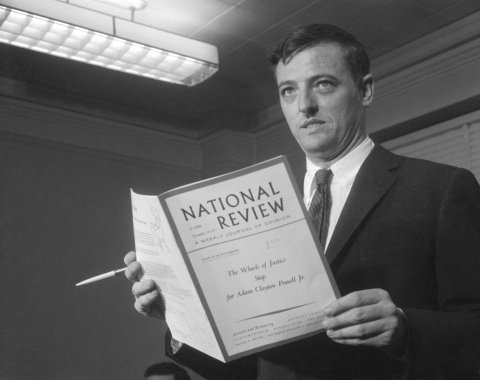

Charles C.W. Cooke is editor of National Review Online.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.