On a December morning in 2014, a four-car convoy of black SUVs swept out of the polished limestone arches of the American Colony Hotel in East Jerusalem and drove south. Skirting the walls of the old city, it passed Mount Zion and its small, ancient church where King David lies buried and where Jesus was said to have hosted the Last Supper. Leaving the old city behind, the convoy hit smooth asphalt, passed tower blocks and an art cinema, overtook Israelis travelling to work in turquoise buses and broke out into the terraces of cypress and olive on Jerusalem's outskirts. In 15 minutes, it reached a security checkpoint in front of a towering concrete security wall and was waved through – into Bethlehem, the West Bank, and soon, another world.

On this, the Palestinian side, the roads were potholed and the wall was covered in graffiti and a host of murals by British street artist Banksy. The housing was old and squat, and the cafés and stores empty or boarded up. From the surrounding hills, in every direction, shiny white fingers of walled Israeli housing spilled down towards the city like concrete lava. Cut off from the outside world by the wall, most Palestinians seemed to be wandering the streets simply for something to do.

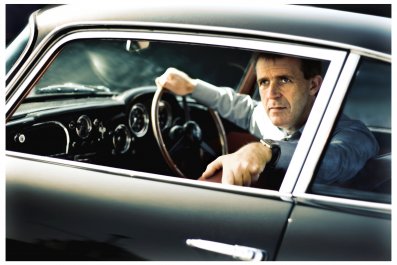

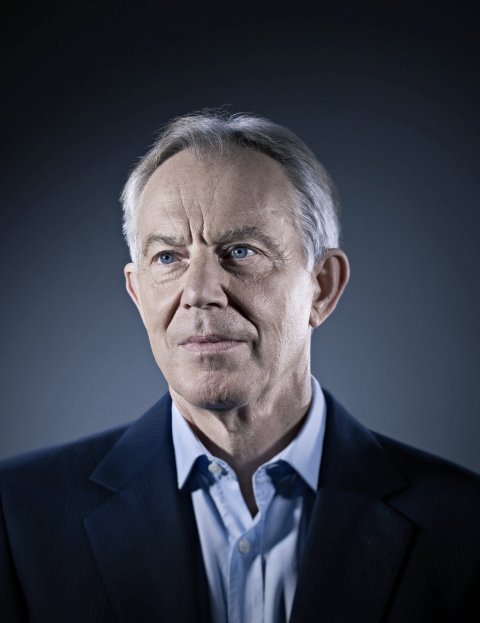

At 61, Tony Blair looked trimmer than when he was in power, more sharply dressed with shorter, greyer hair. He also seemed more at ease: tie-less, tanned, a gold chain visible under his shirt.

His focus for the day was tourism. Since taking the job of Representative of the Office of the Quartet on the day he stepped down as British Prime Minister in June 2007, Blair had been routinely described as a "Middle East peace envoy". In reality, the US Secretary of State mediated political negotiations while the mandate of the Quartet – an abridged version of the international community comprising the US, the EU, the UN and Russia – was more restricted but more pragmatic: building up the Palestinian economy.

The divisions in Israel, which required Palestinians moving much beyond their home to waste hours a day at checkpoints, meant Israelis earned an average 10 times as much as their neighbours over the wall. Even without the politics, that disparity all but guaranteed more conflict. And with historic sites like Bethlehem, Jericho and the Dead Sea, plus Roman, Persian and Ottoman ruins – and even Banksy's murals – the best hope for a thriving Palestinian economy was tourism.

The lifelessness that now confronted Blair in what should have been the pre-Christmas high season illustrated how dead the political process was. In the summer, Israel had fought a war with the Palestinians in Gaza, the narrow and dismembered Palestinian strip on the Mediterranean. As the bullets flew and peace evaporated, the tourists vanished. Still, the economy was Blair's mandate and that meant tourism, so his convoy was soon pulling up outside the Palestinian tourism and antiquities ministry.

Minister Rula Ma'ay'a's third-floor office was cramped and cheaply furnished. On the walls were ancient tourist posters depicting Palestine in the 1930s, before the creation of Israel in 1948. Once, the posters had been advertisements. Now they assumed a more weighty purpose: artefacts of a diminished identity and a disappearing homeland.

Gamely, Blair tried to stick to his mission. "We're working on a package for Christmas tourism," he said. "What do you want the Israelis to do?"

The minister regarded him. "What do we want them to do?" she repeated.

Blair realised his mistake. "Well, apart from the obvious . . . " he began.

"What we want," interrupted the minister, "is for them to leave Palestine and give us our independence back! They promise and promise, and you try to help, but we get nothing from them."

"It has been promised for a long time," Blair said.

"The Israelis want everything for themselves!" exclaimed the minister. "They do not want to give us anything. I used to say they gave us peanuts. But they do not give us peanuts now! They give nothing!"

"We are working to try to change things," Blair tried again.

"I think you should push more," replied the minister.

Blair, momentarily defeated, sighed.

"It's tough," he told the minister. "It's really tough." Then he inhaled, raised his eyebrows, opened his arms in a wide shrug and made a fish mouth, clamping his bottom lip over his top one, an expression members of his staff call his "shit-happens-move-on" face.

"How can we help?" he asked.

"I've done British"

Last month, reports appeared in the British press that, after making little progress, Blair had been asked to retire as Quartet Representative. His office countered that, in reality, Blair was frustrated by the narrowness of his role and was himself proposing a move to a newer, bigger one: more political, more regional, though still appointed rather than elected.

This vision of a pivotal place for a self-selected leader in the middle of the world's most volatile region, reflected views Blair has been developing for years. Even as he approached the end of his time as prime minister in 2007, Blair said he was sketching out "an absolutely clear view of what I wanted to do, and why, from the moment I left office". Free to make his own choices, he determined he would focus on three contentious, wide-ranging areas: the Middle East peace process, religious extremism and African governance.

"I've done British," he said during one of eight interviews with Newsweek conducted in Sierra Leone, Israel and London during November and December 2014. "I suppose where I think I can make most difference is a global level, working on things that had interested me as prime minister but I was not able to devote myself to."

Blair was also impatient to try out some unconventional ideas on leadership. In particular, running a country as an elected democrat made him wonder how it would be to work as a non-political, unelected leader, unrestrained by events, bureaucracy, electorates, opposition or the press, able to pursue results rationally, with pragmatism and without distraction.

To fight religious extremism, he established the Tony Blair Faith Foundation, an independent, self-funded organisation that promoted a tolerant and inclusive vision of faith that was "about compassion and service to others, a set of values which all the large religions share".

It worked primarily through education and using religious networks for practical purposes, such as training imams and preachers how to prevent malaria.

He also set up the Africa Governance Initiative (AGI), a small team of efficiency consultants whom he dispatched to those governments in Africa (eight, at the latest count) that he judged to be genuinely interested in advancement. Rather than traditional aid workers, who tended to instruct or supplant national governments, then take their expertise with them when they left, Blair believed African rulers were best placed to know what their people wanted but that, like any government, they could always use some extra training and advice on how to do that. AGI was to pursue permanent progress that raised "the capability of the country to implement sensible decisions for itself".

Even as his ideas were still evolving, Blair's ambitions for his organisations were instinctively large: to be "of sufficient weight and influence that they change global policy". The Faith Foundation would create a new global consensus around the importance of tolerance, just as the greens had with the environment a generation earlier. The AGI would revolutionise aid. Blair agreed to lead the Quartet in addition because it combined his interests in one job: fighting religious extremism and promoting good governance. Far from being dissuaded by the conflict's intractability, to Blair the failure of conventional politics was a chance to experiment with something unorthodox.

The Middle East was a prime example of politics "getting in the way" of peace, he reasoned. The negotiators were all politicians, elected leaders, diplomats and militants, whose positions depended on their adamant defence of their constituents: for the Israelis, not giving an inch on security; for the Palestinians, not giving an inch on land. Progress was impossible. What was needed, Blair argued, was an independent executive, an unelected outsider who could focus solely on peace, and take risks and pragmatic steps to achieve it. After all, he maintained, the solution to the impasse was "perfectly obvious": two states living side by side, separated by a frontier based on the old 1967 border, adjusted for land swaps, that adequately compensates Palestinians for land lost to Israeli settlements. It should have been a simple, technical negotiation.

Moreover the question of whether "two peoples living side by side in a very small stretch of land" could do so in peace was, said Blair, about practical measures to build trust. "That's about how people feel," he said, "the Israelis about security, the Palestinians about prosperity, ease of movement, their daily life. Imagine a situation where there was some basic shared economic prosperity and some basic cultural acceptance. How hard would it be to reach a peace agreement? The answer is not very hard at all."

In practice, that meant building a stable, viable Palestinian state in everything but name and convincing Israelis that a happy Palestine was "their best insurance against extremism". This balance was not something anyone with a constituency could readily accomplish. But Blair was free to both oppose the blockade on Gaza, whose poverty he called a "rebuke" to leaders on all sides, and argue against those who blamed only Israel for the conflict.

And in the beginning Blair's ideas produced results. He persuaded the Israelis to dismantle many of the more irksome restrictions on Palestinians. Around 170 checkpoints, roadblocks, gates, fences and trenches were removed and their opening hours extended so that it became possible to drive the length of the West Bank passing just two or three manned checkpoints. Blair also negotiated more permits for Palestinians to work in Israel, more power, a mobile network and an expansion from 100 to several thousand in the list of goods the Israelis allowed into Gaza. Partially as a result, in 2008 Palestinian wages rose by 20% and trade by 35%. In 2009, economic growth hit 8%, then 9% in 2010, when tourist numbers rose from 2.6 million to 4.6 million in a single year. By 2013, annual trade between Israel and Palestine was worth a shared $20bn (€18bn). Trade to Jordan also rose 30% in the year to 2013 and 50% to 2014.

But when the Gaza war erupted in the summer of 2014, the new stability fell apart. Tourist numbers fell by 60%. Unemployment rose to one in six in the West Bank and one in two in Gaza. The Palestinian economy shrank by 1%. By the end of 2014 a quarter of all Palestinians and a half of all Gazans lived on $2 a day or less. The atmosphere became febrile. By last December in Jerusalem, Israeli soldiers were guarding Jerusalem's al-Aqsa mosque against Zionist extremists and there had been a series of Arab attacks on Jews.

The day after Blair arrived, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced he could no longer work with the moderates in his government, fired them and, three months later, won re-election by ruling out a Palestinian state.

In West Africa a month earlier, where his staff were helping to fight Ebola, Blair would compare the disease to the Middle East and conclude the latter was "the true nightmare". In Jerusalem, he said the peace process was at "a very dangerous moment" in which "both sides have given up on faith in the other".

Blair vowed not to give up on either. His December visit was his 127th since 2007, an average of a trip every three weeks for seven and a half years. But he conceded there was no denying that, despite his efforts, the peace process continued to be a world-beating example of "bad politics".

Son of the copy boy

Tony Blair's father, Leo, was the illegitimate son of two travelling English actors. The caravans of a theatrical troupe touring the British regions in the 1920s was no place to raise a baby, and the couple sent Leo to a foster home. From there, he was adopted and taken to Scotland by a Glasgow shipyard worker called James Blair and his wife, the daughter of a butcher.

Growing up in Govan, one of Britain's most deprived neighbourhoods, Leo's first job was as a copy boy on the communist Daily Worker. In 1948, he married Hazel Corscadden from a Northern Irish family and the couple settled in Edinburgh. They had a first son, William, in March 1950. A second, Anthony Charles Lynton Blair, arrived in May 1953, the same month Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay climbed Everest.

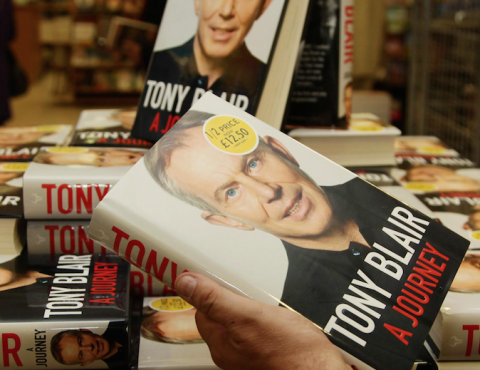

In time, Leo prospered. He became a tax inspector and, after studying law at night, a barrister, a law lecturer, a member of the Conservative Party and an aspirant MP in the new family home of Durham, just over the border with England. Leo's journey from Govan to an elevated position in the Establishment crossed the entire social, economic and political spectrum of 20th-century Britain. Blair's critics would later see precedent in Leo's transition. Tony also graduated from doctrinaire socialism in his adolescence to become a lawyer, a pro-business centrist in his politics and, socially, a friend to the rich and powerful. He even called his autobiography A Journey.

But such a simplistic view was a misreading. Leo was a militant atheist and Hazel an Ulster Protestant, but Tony was an ardent Christian who eventually converted to Roman Catholicism. It was his faith and the Christian principles that underlay social democracy that forever tethered Tony to the politics of the centre-Left. If Leo's progress did guide his son, it was in ways his opponents mostly missed. What some saw as a narrative of self-serving expediency would have been, to those inside it, an inspiring story of hope and a testament to the power of pragmatism.

The lesson Tony took from his father was romantic, and heroic. The optimists in life were right. From the lowest ranks even the highest ambitions were justified. Anyone could make it. All that was needed was hard work and a little flexibility and incredible success was possible.

Blair's spectacular political career was further validation of this sunny outlook. Defying the truism that all elected politicians fail in the end, Blair's defeat in his first election in 1982 turned out to be his last. In 1983 he won the seat of Sedgefield, near Durham. A year later he was appointed to the opposition front bench as a finance specialist, rising to the shadow cabinet in 1987, shadow Home Secretary in 1992, and Labour Party leader in 1994. After transforming the party from dour, stubborn socialism to the electable welfare capitalism of "new Labour", he won power in 1997, then again in 2001 and 2005, a record better than any Labour leader in history. When he left politics in 2007, it was as part of a previously agreed, if fractious, handover to his deputy, Gordon Brown.

Blair's achievements in power were dramatic. His government brokered peace in Northern Ireland. He was a pioneer of aggressive and high-minded intervention overseas, sending British troops into wars of humanitarian purpose in Kosovo in 1999 and Sierra Leone in 2000. He adopted many of the aims of aid activists, leading the campaign for banks to drop Africa's billion-dollar foreign debt and persuading the rich world to raise foreign assistance to Africa by tens of billions more. At home, new laws wrought fundamental change and formed his legacy: devolving power to Wales and Scotland, streamlining public services, setting a new minimum wage and allowing gay civil partnerships.

Perhaps the biggest change to Britain under Blair was one of character. By the time he left power, a 20th-century country of tradition and history had become a 21st-century nation of populism and materialism. Muddling through became maxing out. Fame became celebrity, an end on itself. Totems of British greyness – bad food, terraced housing, tatty pubs and rain-drenched football – were all given glamorous makeovers.

Not all of these changes were at Blair's instigation, nor did all benefit him. His populist rhetoric – hailing "a bright new dawn for Britain" as the sun broke on the morning of his 1997 election victory, mourning the "people's princess" when Diana died a few months later – found a receptive audience. But with Britain's new touchy-feeliness came a new taste for hysteria. In the years that followed, mob frenzies erupted every few months over paedophiles or immigrants or terrorists or murdered schoolgirls. The privilege of power – never explain, never apologise – was replaced by the burden of it: endless justifying and repeated public apologies.

Leading this mood of outrage and mistrust were the British press. Newspapers pilloried politicians as corrupt and out of touch, terrorising those they caught padding their expenses or not knowing the price of milk. There was little room in this narrowed public debate for the kind of flexible and pragmatic middle path – "The Third Way" – that Blair represented. The poisonous bullying of Blair's press aides, still smarting from Labour's long wilderness in opposition under Thatcher, also came back to bite him. After initially idolising him for his energy and youth, the press now decided they hated him for his deal-making: too slick, too smiley, too clever by half.

As Britain's democracy turned on Blair, he, in turn, felt increasingly alienated from it. When he became prime minister in 1997, he wrote in A Journey: "I had started by buying the notion, and then selling the notion, that to be in touch with opinion was the definition of good leadership."

A decade later, "I was ending by counting such a notion of little value and defining leadership not as knowing what people wanted and trying to satisfy them, but knowing what I thought was in their best interest and trying to do it. Pleasing all of the people all of the time was not possible; but even if it had been, it was a worthless ambition."

That estrangement only grew after he left public office. Rather than retiring quietly, the 54-year-old Blair infuriated the press by embarking on a new prominent career which he funded by yet more deal-making, as a commercial consultant to business and governments. In time, he became the target of a peculiarly British pack catharsis, cynical, belligerent, thin on facts, long on bile, not unlike a lynching (or, to use Fleet Street's own word for it, a monstering).

Today Blair's name is a headline swearword and a Pavlovian trigger for many normally level-headed Brits to froth at the mouth. White, male, powerful, rich – and originally from a party that once disliked all those things – Blair is the focus for a kind of righteous hate speech. Many Britons consider him to be a Machiavel with a Messiah complex, a war criminal who claims – the deviousness of the man! – to be saving the world.

He is said to be a fixer for dictators, bankers, media barons and billionaires, a method actor who believes his lines, a globe-trotting Iago with a penny-pinching addiction to free holidays who charges a small fortune for a 45-minute speech, and more for advice, and whose speed-dial is a diabolical list of 21st-century power, fame and money. In a presentation to Blair's staff, a London public relations firm compared Blair's relations with his public to a bitter divorce. Blair seduced them, deceived them, then left them for a happy and solvent new life – and they were not getting over it. Blair was up to something. He'd always been up to something. Lied about Iraq. Probably lied about everything. Always seemed to make out himself. Insufferable, slippery, greedy, shameless, sun-tanned bastard.

Driving in circles

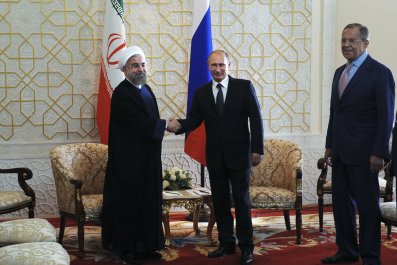

On 4 December Blair wrote an essay in The New York Times headlined: "Is democracy dead?" He began by stating that democracy was certainly "not in good shape". US politics were deadlocked in partisanship. European politicians were not delivering a return to growth. The democratic Arab Spring had been largely outmanoeuvred by the old regimes. Democracy was failing, he wrote, and, worse, the challenges before it – extremism, financial crisis, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea – were rising.

Blair had sharpened his ideas about leadership and the failings of democracy in the years since he left power. Democracy, he now concluded, faced an "efficacy challenge". "Slow, bureaucratic and weak," it was too often "failing its citizens" and "failing to deliver". The price was grave, and apparent. Without effective action by democratic governments to stem it, volatility and uncertainty were spreading. Public fear and disillusionment was stoking the return of the far Right in Europe and the United States. "Suddenly, to some, Putinism – the cult of the strong leader who goes in the direction he pleases, seemingly contemptuous of opposition – has its appeal," wrote Blair. "If we truly believe in democracy, the time has come to improve it." Every few years, democracy was about the people's vote. But most of the time, it was about their elected representatives harnessing the machinery of government to effect change on their behalf. Attempts to be a cipher for popular opinion Blair dismissed as "governing by Twitter". Leaders had to lead.

That wasn't happening. Centrist democrats were lost in the chaos and instability of the times. That left space for "quack remedies" as he put it – "emotionally attractive but practically foolish or even dangerous debate around immigration – [which] are being peddled by extreme versions of Left and Right". Then there was the press. Blair saw an ever slimmer divide between journalist and internet troll. He said it was "never pleasant" to be under attack, but argued that whatever personal beatings he took, democracy was taking a worse one.

To Blair, the way the press charted economic decline or international crises or terrorism with methodical sensationalism, then woke up to depress its readers afresh the next day, bordered on masochism. The British media seemed in danger of giving up its primary function: mediating information. His December Middle East trip was a case in point. While Blair was in Jerusalem trying to patch up the peace process, he was making headlines at home for smiling weirdly on his Christmas card.

"I try not to think about that too much," he said. "It just does my head in."

This was not constructive criticism, said Blair. It was a "wall of noise" that was crippling democracy. "This is a shocking thing to say," said Blair, "but in modern politics, if you are spending 30% to 40% of your time on your real core priorities, I think you're lucky. I can think of political leaders and systems who are lucky if they get 5%." Agendas were more packed than ever, crises came ever thicker and faster and yet leaders were spending all their time "communicating". The core functions of government were being forgotten, Blair said. All but gone was any time to consider "the big questions". "You know," said Blair. "Where are we going? What are we trying to do here? What's it all about?" Blair viewed the resulting paralysis with disdain. "The wheels are spinning and the vehicle is moving" but the result was often just "driving round in circles".

Blair said that many veteran leaders agreed "the whole business of government . . . has just got to change radically to be effective". If politics as usual wasn't working, then the pragmatist's response had to be to search for answers outside it. "Democracy is a way of deciding the decision-makers, but it is not a substitute for making the decision," he wrote in the Guardian in 2013. "Democratic government doesn't on its own mean effective government. Efficacy is the challenge."

In Egypt this March, Blair went further, praising the military regime of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, which has restored some stability but at a price of torturing and killing opponents and imprisoning journalists. "Yes, democracy is important, but democracy is not on its own sufficient," said Blair. "You also need efficacy. You need effective government taking effective decisions. I don't think you have to be authoritarian. But you have to be direct."

Blair took much of his inspiration from business: "You can be a great communicator, which gets you the job," he told a mining conference in South Africa in February 2015, "but once in power, you're a CEO and need to run a business". After all, said Blair, business was pragmatism. It was efficiency-obsessed, executive-led and constantly looking to innovate. Businesses dreamt up products, tested them with audiences, then made, marketed and distributed them as efficiently as possible. Blair proposed governments should do the same with policy. "There should be no shock about this," he said. "In a world in which you think of every other walk of life and the changes that have come about in it, it would be odd if government didn't have the same necessity to change." The trouble was that since bureaucracies didn't go out of business, they hadn't felt the need to change. They should be made to understand that saving democracy demanded it, and take their lead from those for whom change was survival.

Blair wasn't proposing that the world be run like a corporation. He was saying that inside a democracy it was executive power that delivered results. His own method in power had been to study an issue, canvass a wide spectrum of opinion, even listen to the press and hold a public referendum; then note the debate, thank its participants, come to his own conclusions, and lead. "It wasn't that I didn't have doubt or hesitation or uncertainty," he said. "You can't be sure. But I'm for taking that big decision. It's less to do with certainty than a big solution to a big problem."

Blair was saying there was a time for talk and a time for action – and that a leader's duty was to stay the course. "I decided a long time ago that it's about whether I'm doing the right thing or the wrong thing," he said. "If it's the right thing I'm doing, if I'm doing what I think is right, then I should be doing it even though people disagreed, even if I am being attacked for it. If you always worry about why there is so much static, if you live your life by that, you end up not doing very much."

Too little, too late

"So we still have a gap on beds of about a third," said Blair. "Wow. To what extent is the president? I mean, look, if this was me … Does he get a daily briefing? Is he not on top of this day-by-day, going through all this all the time? Is he running this? Kate?"

"I don't think so," said Kate. "I don't think people have been honestly advising him. The official stats are also quite inadequate. He's not getting a clear vision."

Blair shook his head. It was November 2014, a month before his trip to Jerusalem. Blair had arrived in Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, at 06.20am by overnight private jet from London. At the plane's steps, he had his temperature taken by a thermometer gun held to his forehead. Then, careful not to shake hands but holding his hand to his heart and bowing in the newly prescribed fashion, he met the acting minister of foreign affairs at 06.25am, caught a speedboat from a wooden jetty across the turquoise sea to Freetown at 06.50am, transferred to a convoy of black SUVs with police outriders on arrival at 07.20am and reached the Radisson at 07.25am.

At the entrance, he washed his hands in chlorine solution, had his temperature taken once more, then caught the lift to his suite where, in the 45 minutes marked on his schedule as downtime, he showered, changed into a fresh suit, made calls to the UN and the World Bank, did a live interview with Sky TV in London and reviewed his schedule for the day – 12 hours of 16 back-to-back meetings before an evening flight to Liberia and a staff dinner after that. At precisely 08.10am, he had ridden back down to the lobby, crossed it at such speed that his bodyguards had to jog to keep up, and entered the hotel's conference room.

Blair now sat with his back to the window at the head of a long table on which several plates were piled with croissants and pastries. To his left sat Kate Dooley, the Australian head of his Africa Governance Initiative in Sierra Leone, and around the table were Dooley's staff: half a dozen young people in suits. The table was decorated with small, neat piles of BlackBerries, schedules and briefing folders. Everyone had immaculate hair. Nobody was touching the food. The only visible clue to the disaster unfolding out in the sweltering city and, beyond – a viral swarm that would near a global total of 25,000 cases and 10,000 deaths by March 2015 – was a flip chart on which Rupert Simons, another of Dooley's staff, had drawn a spread-sheet in marker pen which read:

Now (Nov 11) Dec 1

Cases per week 500-1,000 1,400-1,800

Burials 300-600 1,000-2,000

Treatment beds 300 1,800

Isolation beds 800 (500 in wrong place) 1,400

The good news, Simons said, was that Ebola's rate of increase in Sierra Leone had slowed, from doubling every 30 days to every 60. But Simons had plenty of bad news. To beat the virus, he said, you had to isolate and treat the infected, and burn or sanitise the dead, plus everywhere they'd been and touched. All were currently impossible tasks.

In the first instance, moving the infected to treatment wards was hard. There were not enough ambulances in Sierra Leone, those that existed were often filthy with infected blood and dying people didn't want to leave their families. Then, even if the sick agreed to be transported, Sierra Leone had half the 4,000 health workers it needed to treat them when they arrived. If people died, which they sometimes did in their hundreds in a single day, cremations and quick burials in sealed body bags violated most West African burial customs. But the single biggest problem, said Simons, was the week to 10 days it was taking for the results of an Ebola blood test.

"It's dangerous having people waiting in an isolation facility if they have not got Ebola, because they will be around people who do," he said. "People are getting Ebola in the isolation wards. And they are dying; 60-70% of people who get Ebola die."

That was treatment. Blair made a few notes, then asked about resources. "What have we got in Freetown at the moment?" Dooley's number two, Victoria Parkinson, spoke up. "One major treatment centre," she said. "The Chinese opened a second one but have done a pretty shocking job, to be honest. They just lock them in and watch them on CCTV." Blair nodded. "Burials are a highlight for us," continued Parkinson. "But we haven't enough holding room. Yesterday we had one of the worst days. We left 60 people in the community who might have Ebola."

Dooley then gave a regional summary. The scale of what was necessary to beat Ebola grew every time they examined it, she said. The latest information from Nigeria indicated that to eliminate the threat from a mere 20 cases, the authorities had had to go door-to-door and test an eventual 20,000 people. Assuming similar metrics for Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea-Conakry, that would mean testing the entire population of 11 million-plus.

Dooley said that help in co-ordinating this vast mission might have come in the form of the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER), created two months earlier. But to date, the new UN body had proved as lethargic as the rest of the UN had been throughout the crisis.

"So far, there are 11 people and they are not doing a whole lot," she said. "I mean, they're based in Accra." Accra, capital of Ghana, is hundreds of miles away in a different country, one unaffected by Ebola. UNMEER chief Tony Banbury was at that time in New York. "UNMEER is an unknown entity," said Dooley. "I think even to themselves at this stage."

Blair's scheduler stuck her head around the door. "Our key message to the president," said Blair, as he stood up, "has to be that he has got to know every day what he wants from the international community. He should be on the phone to Ban Ki-moon, asking, 'C'mon, what the hell are you doing?' Can we brief him on how to do that?"

Blair's Africa Governance Initiative derived, in part, from another of his observations during his time in elected government: that one of democracy's biggest flaws was its inherent amateurism. "What I do think is bizarre is that [in] politics you can literally come from no experience of running a government at all to being head of a government," he said. "Imagine that for manager of Manchester United, there was a competition among the fans, which ended up making one of them manager. Or choosing the leader of IBM on the basis that they had written a great article about IBM. Those would be absurd, the most ridiculous thing you ever heard."

Along with sending in consultants, Blair himself was drawing on his experience to advise serving presidents and prime ministers. One day he hoped to have a small cadre of ex-leaders who he could deploy in the same way. Only leaders truly understood leaders, he said. "The moment I'm talking to a new leader and I'm describing what I felt and what the challenges were, there's a total and instant empathy, an immediate locking on to each other. Whether they come from the Left or the Right, what they want is to get things done. And I know what it's like because I've sat in the decision-making seat."

The Africa Governance Initiative had been running for six years by the day, in December 2013, when a two-year-old boy, who liked to play with fruit bats nesting in a tree stump near his home in the southern forests of Guinea-Conakry, contracted Ebola and died. The outbreak's location, remote and close to the borders of Sierra Leone and Liberia, hindered attempts to track it. So did fear. In June, aid workers in Freetown were saying they would leave if the disease hit the capital. When Ebola exploded in Freetown a few weeks later, many did, along with scores of Sierra Leonean doctors, of whom there were only 200 in the whole country. In Liberia, government ministers fled.

In all three countries, some foreign medical charities and thousands of local health workers stayed to treat patients and dispose of the dead. The US, Britain and France dispatched thousands of soldiers. But without an effective central government command to map the disease and co-ordinate efforts, the epidemic continued to grow. The African Governance Initiative happened to have small teams of economic consultants in the president's office in all three Ebola countries. As the need for a state command structure became clear – and as defeating Ebola was a prerequisite for having an economy at all – Blair's teams volunteered to switch focus and help build it.

That was three months earlier. Now, Blair was visiting all three Ebola countries in two days to review AGI's progress. From the conference room, he walked with his staff to the convoy of black SUVs waiting out front. With outriders racing ahead, it took 20 minutes to cross Freetown, a bustling seaside city of wooden houses, tin roofs and street side markets. After meeting the president and his staff, and a tour of Parkinson's Freetown Ebola response centre, Blair's convoy drove on to the National Stadium. Another wash and check, and a British army lieutenant walked Blair through a training centre her men had built to drill hundreds of Sierra Leonean health workers in how to safely handle Ebola patients. The tour ended with an interview with Alex Thomson, a veteran reporter from Britain's Channel 4 News.

Thomson was aggressive from the start. "Quite honestly, it's too slow," he said of the efforts to stop Ebola. "Too little, too late. You're a hero here – and it's not often that you get a journalist who'll say Tony Blair did an extraordinary intervention in a country – so what happened? Did we take our eyes off the ball? How did we allow this to happen in all of these countries?" Blair, a little winded, replied that he believed a real effort was being made, though he conceded more was needed. "The real tragedy is that Sierra Leone – and my people have been working here for many years now – actually really was moving forward," he said.

"Last year's growth figures were amazing. I've been driving on roads today that didn't exist a few years back. If this had come in four to five years' time, I think we would have been in a different position. One of the big challenges is how we rebuild the economy and Sierra Leone after this disease is knocked out."

Thomson wasn't listening. "You have commercial interests which extend to mining in this region . . . " he said.

"I don't, by the way," said Blair.

"Well, we understand you do," said Thomson.

"No, I don't," said Blair.

"Do you deny that?" asked Thomson.

"Absolutely," said Blair. "I don't have any mining interests in this region."

"Through consultancy and so forth, the companies you're involved in . . . " said Thomson.

Blair shook his head.

"Be that the case or be it not," Thomson said, "the question is: is industry doing enough here? A lot of companies are getting very rich, these countries remain desperately poor and Ebola strikes at the poorest. With Afghanistan and Iraq, today areas like Sierra Leone just get demoted."

It was an astonishing question. Thomson had somehow managed to smash suspicions about Blair's wealth and capitalist greed in general, plus Blair's record in office of pursuing war in Afghanistan and Iraq, into a question about Ebola and one that implied Blair and his crony capitalist friends didn't care about Ebola – when here he was in middle of the Ebola zone trying to talk about Ebola, when his staff had stayed on to build the organisation that would be instrumental in defeating Ebola, if only Thomson would shut up and listen.

Blair didn't actually say that, of course. Later he did say: "Look, I don't have any mining interests in Guinea. I do consult for JP Morgan so maybe you can make a stealth accusation or something . . . But it's not unreasonable, is it, to say, 'Look, I am trying to deal with Ebola here'?" At the time, however, Blair merely shrugged, made the fish mouth and said, "Well. Mmph. I don't think so, actually."

Shit happens. Move on.

Benevolent dictator

By late last month, Ebola was in abeyance. A bigger test of Blair's belief that good things come to those who try was his work in the Middle East. On that December trip, his clarity and focus gave him an irrepressible energy. He was still rising at 6am and working until midnight or even through the night. Giant problems that might have deterred others were to Blair merely "things" that a good leader could overcome or think around. Seething press hostility was a "political thing". The strikes of 1980s Britain, which saw thousands of pit workers in pitched battle with riot police across the country, were "the miners' thing". The reform of predatory and occasionally rampaging African armies was "another thing I'm interested in".

On the drive to Tel Aviv airport at the end of his visit, I asked Blair how he was so sure he had the solution for a conflict that had eluded so many others for so long. "Well, I've thought a lot about it," Blair replied. He had been dealing with the Middle East for 20 years. He'd long ago worked out a formula for peace that mixed the political, social and economic. It really wasn't all that complicated, once you thought about it. "And I guess to me it's just very simple that once you come to a particular conclusion of what will solve this problem, you want to get on with it, and do it."

In Liberia, Blair had said that the British military's slaughter of 10 million sheep and cattle during the 2001 foot and mouth crisis taught him soldiers were better at emergencies than governments. At times like those, Blair's ideas of leadership could seem close to benevolent dictatorship. Not least because he called the world's most famous benevolent dictator, the late Lee Kuan Yew, founder of Singapore, "the smartest leader I think I ever met" in a book dedication in 2013. "Some people felt that the measures they took were pretty tough," said Blair in an interview. "But Singapore is a functioning state of a very high order today because of the decisions they took."

Blair accepted that his views could be antagonistic to the democracy he wanted to improve. Partly, he said, that was the inherent tension between executive power and people power. A leader would always face dissent, on any issue. His opponents' fury was "completely understandable" and they were "absolutely entitled" to their views, he said. But that didn't make them right. And that meant, obviously, that the results-oriented leader shouldn't take these views into account. Opposition was the price paid by true leaders. Weathering the storm was the test of them.

It was exactly that kind of thinking that got Blair into so much trouble over Iraq. Benevolent dictator or hard-nosed pragmatist, a leader of Blair's conceptualisation had to be right. And on Iraq, many felt Blair was wrong.

His decision to invade was never popular. Twelve years later, it is a shorthand for everything that so incensed his detractors. Asked about it, Blair gave a succinct summary of his thinking in the approach to war. Global security had changed "completely" after 9/11. Three thousand people died in New York but it could have been 300,000 – al-Qaida didn't care.

"That led to a completely different security paradigm," said Blair. "The United States believed – and I believed that it was important that we stood alongside them in this – that we had to take a completely different attitude to nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. And Iraq was the place to start because since the Second World War only one government had used such weapons and that was the government of Saddam Hussein."

For using chemical weapons twice, against Iran and against the Kurds, Saddam was first up in America's crosshairs. After him came Iran, North Korea and any other regime Washington didn't trust with mass casualty weapons. Blair more or less agreed with America's assessment. "People can debate," he said, "but I personally think Saddam would have turned out to be a threat had he been left there." He also felt that sticking with America was a good strategy in its own right. "I felt it was important that we stood with America in the post-9/11 world. I still think that. The nub of it was that."

Many Britons disagreed. They felt the US decision to take on and subdue any threat in the world was a dangerous over-reaction. Blair's decision to support Washington come what may also felt like submission rather than what they would have preferred: friendly but firm counselling against rash action. Public anger at what many accounted Blair's mistakes led to four public inquiries, including the current Iraq inquiry led by Sir John Chilcot.

There was an awesomeness to Blair's unstoppable engine. But there was autocracy to it, too. All his I thinks, I believeds and I felts could sound self-effacing. But they could feel presumptuous as well. People can debate. They could, and they did, but in the end it didn't really matter. In the weeks before the Iraq war, hundreds of thousands of anti-war protesters marched through London. But, according to diplomats and officials giving evidence at the inquiries, Blair had decided the naysayers were wrong as much as a year before. He did try repeatedly to persuade them and spent years attempting to do so in retrospect, even when some – five, at the latest count – tried to effect a citizen's arrest on him for war crimes.

He has also admitted there had been insufficient planning for the war's aftermath and defective understanding of how radicalism, not democracy, might fill the vacuum left by Saddam. But he knew the invasion was right and he was the national chief executive. He had made up his mind. Britain should go to war. So it did.

In the years since, Blair has received almost no credit from Britons for his work in Africa or the Middle East. When he does – such as when he was given humanitarian awards by GQ magazine or Save the Children – it's a press scandal.

In the end, it was Blair's leadership to which his opponents objected. Criticism, ambivalence, hindsight, regret, an indulgent appreciation for human imperfection – these were characteristics by which Britons defined themselves. It was why many see efficiency as akin to authoritarianism. Certainty was for extremists; doubt was democracy. A leader who merely listened, then made his own decisions – that was an American president. A British prime minister was meant to be a lesser figure, tethered to a series of collectives from Cabinet to government to parliament, party and nation. Even in a changed Britain, Blair's version of leadership was a modernisation, an Americanisation, too far. He wasn't just doing what the Yanks wanted. He wanted to be one, too.

The 'secret Zionist'

Six weeks after his December visit to the Middle East, Blair was in Davos, Switzerland, for the 45th World Economic Forum. He was speaking on a panel entitled: "Religion, a pretext for conflict?" Blair argued that though it hadn't always been the case, modern extremism was often founded on a perversion of religion. When the audience was asked for questions, Henning Zierock, a German socialist, countered, to a smattering of applause:

"I think you have great responsibility for the conflicts we have now."

On his way out of the venue, Blair was barracked by British reporters. "If you are invited to the International Criminal Court, will you attend?" asked one. Another asked him about the Iraq inquiry's decision to delay publication of its findings until after a British general election in May. "Did you cause the delay?" asked the reporter. "Do voters have a right to know the contents of the report before an election?"

The questions reflected beliefs common among Blair's opponents: that because he invaded one part of the Middle East, he was uniquely disqualified to be making peace in another; that he must be punished for his mistakes in Iraq; and that if he wasn't, it was probably because of some corrupt insider deal. These suspicions dovetailed with other dark mutterings: that Blair consulted for the banks and corporations that have misruled the world; and that he has parlayed his contacts and inside knowledge into lucrative favours and deals that have catapulted him, personally, into the number of the extremely wealthy. At its most diabolical, the allegation was that Blair used the office of prime minister as a mere stepping-stone to a life among the über-elite. His was, so the talk went, the ultimate sell-out.

In response, Blair claimed the obsession with "honesty and transparency" – his own, or other politicians – was misplaced. Most politicians were decent and hard-working, he maintained. In his own case, the attacks on him came "from people with whom I continue to have a profound political disagreement" about how to approach the Middle East but who tried "to dress it up as something else – conflicts of interest and that type of thing".

It did seem unlikely that if Blair were a secret Zionist, as his detractors claimed, he would have attracted 50 young, bright, serious and worldly Palestinians and Israelis to his office in Jerusalem, many of whom took a pay cut to work for him. It seemed just as unfeasible that if he were only out for himself he would be repeatedly trusted by foreign authorities – Palestine and Israel, and Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea-Conakry – to intervene in their gravest national crises.

Asked at his offices in Nablus what he thought of the idea that invading Iraq made Blair an unsuitable envoy to Palestine, Palestinian deputy prime minister Mohammad Mustafa seemed perplexed and a little insulted at the conflation. "We do not focus on what he did in Iraq," he said. "We focus on his mandate to help us in Palestine in the present, and I think he has been doing his best."

The accusation that Blair became rich after leaving office was more reasonable. Blair's office in Jerusalem was funded by those it represents. But to pay for the Faith Foundation and the Africa Governance Initiative, Blair set up two commercial ventures. Windrush, the more successful, with a $14.9m (€13.6m) turnover in 2013, marketed Blair as a consultant and speechmaker to governments. Firerush, did the same for business. Blair estimated that he spent three-quarters of his time on his public service work and the remainder on his commercial work. He said the latter paid for the former: "I couldn't do what I do unless I was also able to generate income."

Still, Blair acknowledged his commercial work was not entirely altruistic. He was not paid by the Quartet nor his foundations but rather earned his money from Windrush and Firerush. Though his financial advisers refused to release a full account of his personal finances on grounds of commercial confidentiality, his spokesman said that, together, the two companies have paid him salaries and dividends worth a total of about £20m (€27m) since 2007. From his earnings, the spokesman said, Blair has given £10m to charities, mainly his own. The other £10m is mostly tied up in two houses, one in central London, one just outside in Buckinghamshire. His spokesman said the basis for stories of a Blair British property empire seemed to be homes owned by his wife, Cherie, and Blair's four children, for which the Blairs put down surety.

Blair knew an extraordinary array of the super-rich. But even if the wilder reports of his wealth were true, he wasn't one of them. More damaging than the money, perhaps, was that, in earning it, his commercial ventures sometimes worked to lower standards than his public service ones. Speaking of his Africa Governance Initiative, Blair claimed some regimes were too repressive to deal with.

"The prerequisite for us to work in a country is that we think the leadership is trying to do the right thing," he said. "We don't go to countries where they are not. What's the point?"

That principle did not, apparently, apply to Windrush's commercial contract with Kazakhstan. Led by the same man since 1989, a few weeks after Blair signed on as an adviser in late 2011, the Kazakh regime shot dead 14 protesters and injured 64 in the oil town of Zhanaozen. Blair's ideas on good leadership were unlikely to persuade many Kazakhs or human rights organisations, who contended that what the country needed was not more leadership, but less. Equally unconvinced were those who accused Blair of flat-out greed.

Rule by the self-appointed

The day before Blair's appearance in Davos, the World Economic Forum's head, Klaus Schwab, opened the conference by telling his audience they were there because "you are our leaders", brought together "to improve the state of the world". The four-day programme would, he said, "address all the major issues on the global agenda". Participants would first define these problems, issues such as global poverty, disease, war and the environment, then try to resolve them. Schwab had made a head-start, naming "10 big global challenges" that bore a close resemblance to those identified by Blair. Third on his list was "lack of leadership". Fifth was "weakening of representative democracy".

Government began millennia ago with kings and emperors. In time, their power was diluted by religious leaders, courtiers, generals, aristocrats and merchants. The past few centuries have witnessed the steady displacement of all of these by politicians: conservatives, liberals, revolutionaries and, most recently, elected centrists. And now, it seems, power is shifting again.

The World Economic Forum is our foremost example of the rise of a self-selected global elite. It is only one of thousands of new private institutes focused on public service around the world. Many are led by individuals. Blair is one.

Others include the billionaire hedge fund manager George Soros and his Open Society, which bolsters democracy by working through non-governmental activists in 100 countries. Another is the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, founded by the Sudanese telecoms billionaire to work on African governance.

Then there is the $350-million Clinton Foundation, founded by a former President of the United States and a former Secretary of State, which works in health, education and applies a "business-oriented approach to fight climate change worldwide and to promote sustainable economic growth in Africa and Latin America". Biggest of the new groups is the 15-year-old $41bn Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which takes the resources of the world's richest man, and its second richest, Warren Buffett, and focuses them on health, mostly in poor parts of Asia and Africa.

At Davos, Blair declared: "The way the world works today is very simple, even at the very elite level at the World Economic Forum . . . by connectivity. People across boundaries of nations and race and faith coming together, working together, being in community with each other." And it is true that the new global leaders tend to share several criteria. They are either immensely rich or friendly enough with the immensely rich to tap them for funds.

Tellingly, ascending to this new type of leadership does not require a previous career in politics. Some are ex-politicians like Blair and Clinton. Many more are billionaire businessmen, academics, activists, aid workers, philosophers, scientists, even artists and musicians.

The World Economic Forum is where they all gather. Every year Schwab's staff trawl the world of business, civil society, aid, academia and art and pick a handful of young successes whom it anoints as a new crop of Young Global Leaders.

This is not the death of democracy. It is a refinement of it by those winners of the human race whose success alienates them from its imperfections. The WEF cannot pass laws. What it aims to do, explicitly, is influence the debate that informs them, then guide their implementation. This it does through what it calls "public-private co-operation". In practice, that means sharing or handing over issues previously reserved for governments to businessmen and other accomplished individuals.

It is true that these new leaders get results where governments have failed. Gates' work on Aids and TB has saved millions of lives. After decades of government failure, a global campaign against malaria run by a New Jersey billionaire, Ray Chambers, has saved several million more. Partly this is due to the new leaders' hard-nosed, results-obsessed nature. Partly it is because national governments are ill-equipped to cope with international issues like immigration and disease.

But, as with Blair's ideas on leadership, there is an anti-democratic element. The subtext to the WEF, and the think-tanks and aid groups and foundations that are now a vast global industry, is expressly elitist: democracy is failing and they – the rich and capable, the gurus, and movers and shakers – are best placed to help.

While their influence in the West is limited, in smaller, poorer, less functional countries their control is real. Consider the heft that comes with the $57.1bn a year (€52bn) spent on aid in Africa by unelected philanthropists, equivalent to the annual output of 20 of Africa's 49 countries. How that money is spent depends much more on what is said during a panel discussion in Switzerland than anything uttered by Africans. More insidiously, there are questions over how closely the new elite aligns public interest with its own self-interest. Blair uses his contacts for both pro bono and commercial work. He employs an accounting department, a legal department and a compliance department to ensure no conflict of interest.

Still, last month The Sunday Times published a draft proposal from Windrush proposing a consulting contract with the government of Abu Dhabi in which a staff member had ghosted an introduction from Blair that read: "We do both business and philanthropy. All my various organisations are based on the belief that the world today basically works through connectivity. There is virtually nowhere in the world right now where we could not work or provide the necessary contacts either politically or commercially, should we want to."

A spokesman for Blair disavowed the proposal, saying it was a draft unseen and unapproved by Blair, and that the boss had been especially angered by the muddling of private and public. Still, it seems significant that at least one person on Blair's staff should have trouble telling the two apart.

These sorts of accusations loom larger the closer you get to the top. This year, the Wall Street Journal and Washington Post revealed that the Clinton Foundation took $26m (€23.7m)in donations from companies lobbying the State Department when Hillary Clinton was Secretary of State. While the Journal found no evidence of a quid pro quo, it reported that corporations like General Electric, Exxon, Microsoft and Boeing all donated to the foundation at a time when Clinton was pushing their business to countries around the world. The Foundation also took money from many of those foreign countries: $500,000 from Algeria and up to $25m each from Holland and Saudi Arabia.

The Foundation did suspend soliciting money from new donors while Hillary became Secretary of State in 2009, though it continued to take money from existing ones like Algeria, Australia, the Dominican Republic, Kuwait, Norway, Oman, and Qatar. Moreover, after Hillary stepped down in 2013 the Foundation immediately re-opened itself to all donors, government or business, even though Hillary was planning to run for president in 2016.

In Clinton's case, as in the way Bill Gates's wealth has made him the single most influential individual in global health or Soros's has bought power for scores of political groups around the world, there is enough private money funding public interventions to suggest the creation of a new, privately run power structure running parallel to democracy. As Amy Davidson noted in The New Yorker, the Clinton Foundation "is not a normal charity, in its resources or its functions".

If there are paradoxes in the Davos agenda – how did a non-governmental super-class manage to appropriate the subject of governance from government? how did the super-rich reserve inequality as a discussion for themselves? – what's missing is a discussion on legitimacy. In a world increasingly run by the self-anointed, do we now make our CEOs and pop stars as accountable as our politicians – in case their good fortune one day convinces them to try to change the world? Should we choose our computers or movies according to the political beliefs of the bosses who make them? Can we trust a Gates, a Soros, a Blair?

Or do we merely have to hope we can?

In The New Yorker, Davidson noted that the public were left tending the wish that the Clintons were "exceptionally ungrateful to their donors". The same applies to Blair.

If all the noise around him ever swayed him, it really doesn't matter now. Blair has left politics behind. His position no longer depends on others or events or opinions. His is above and beyond, "working on whatever I have chosen".

Blair can fight Ebola, mediate in the Middle East or do business with the tyrant of Kazakhstan. You can't touch him.

A raising of the eyebrows, a shrug, the fish mouth, and he's moved on.