A year after the deadliest Ebola outbreak ever in Africa, the virus has returned. The World Health Organization (WHO) announced Saturday that an outbreak of Ebola in the far north of the country had been declared by Congo's health minister.

Congo was not one of the three countries involved in the 2014-2016 outbreak—Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone—which killed more than 11,000 people, but the country has had several Ebola epidemics in the past.

Here's what you need to know about the latest outbreak.

How big is the outbreak?

There have been 17 suspected cases and two confirmed cases of Ebola in Congo's Bas-Uele province, the WHO's Congo spokesman Eugene Kabambi told Reuters Sunday. Of the 19, three deaths have been reported. Kabambi added that health officials were trying to located 125 people believed to be linked to the cases.

How did it start?

It is not clear yet how the first victim—a man who has since died—caught the virus. But this outbreak is not the first in Congo; the country has suffered seven prior epidemics of the virus since 1976, when the first ever Ebola outbreaks occurred simultaneously in the northern village of Yambuku in Congo and in Sudan.

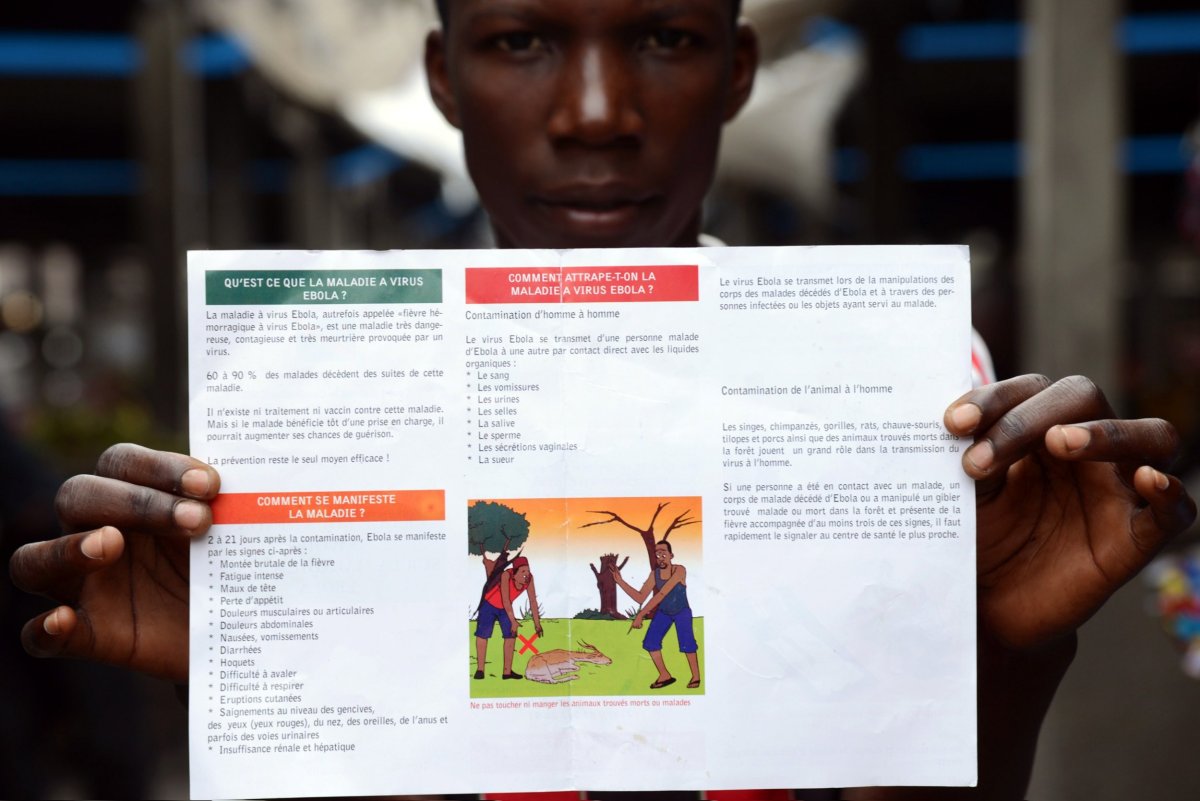

The virus is thought to circulate in several animal populations—including fruit bats, chimpanzees and monkeys—in Central Africa, and several previous outbreaks in Congo have been linked to the consumption of infected animals. A 2012 outbreak in northeast Congo killed 36 people and was blamed on tainted bushmeat.

Once in the human population, Ebola is transmitted via direct contact with the bodily secretions of infected people. Healthcare workers are at heightened risk of the disease, while outbreaks have also been associated with burial practices that involve handling bodies. A 2007 outbreak in Congo killed 183 people, many of whom had attended the funeral of a local chief.

What is the risk of it spreading?

Health authorities are hoping that the remoteness of the region where the cases have occurred may help to slow the spread of the virus. The outbreak was declared in a small town, Aketi, that lies more than 800 miles from the densely populated capital Kinshasa and 81 miles from the provincial hub of Buta.

Kabambi, the WHO Congo spokesman, told Reuters that the first case had occurred in "a very remote zone, very forested, so we are a little lucky." But that same remoteness could make it difficult for health authorities to reach potential victims—Aketi is inaccessible by four-wheel drive and responders would likely have to travel by motorcycle—and the Base-Uele province borders Central African Republic, raising the possibility of a cross-border epidemic.

Will it be as bad as the West African outbreak?

Congolese authorities appear reasonably confident that the outbreak will not escalate to the scale of the recent West African outbreak, which killed thousands across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. That outbreak— which ended in early 2016 as Liberia was declared free of active transmission—was the first in West Africa, while Congo has experience of fighting the virus over decades.

The last Ebola outbreak in Congo, in 2014, was over within four months and killed 49 people; the West African outbreak, by contrast, took two years to contain. The country "abounds in human resources" that have served to "contain similar epidemics" at other times, said Congolese health minister Dr. Oly Ilunga Kalenga in a statement sent to the WHO Saturday.

What happens next?

While it appears unlikely that the situation in Congo will be anywhere near as deadly as the 2014 West African outbreak, health authorities are taking nothing for granted.

The WHO, which was slammed by health experts for being too slow to declare the West Africa outbreak as a public health emergency, has deployed its Africa director to Kinshasa to coordinate a response with Congolese health officials, while charities including Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) have also offered their assistance.

One potentially game-changing development since the 2014 outbreak is the availability of an experimental vaccine that has shown a high degree of effectiveness in fighting the virus. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, has said that 300,000 doses of the vaccine are available to be sent to Congo should the WHO and the country's health authorities determine a mass inoculation program is required.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Conor is a staff writer for Newsweek covering Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, security and conflict.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.