Rachel Stavis has seen demons her entire life—she only started tearing them out of people a few years ago.

"My clients worry that they're losing their minds," the 38-year-old exorcist writes in her new memoir, Sister of Darkness. She says her exorcism service is usually the last resort for tormented people, and that 60 percent of her clientele are public figures, or "names you see in Variety." Before visiting her home-made safe space for expelling entities, most of Stavis's clients have already tried therapy, medication, drugs, energy healing or other methods of self-care. They've been trying to shake off fatigue, negative self-talk or the constant sense that something is wrong.

"The truth is that something has taken over these totally normal, sane individuals," Stavis writes. "What I call an entity—and what people through history have called a demon—has attached itself or burrowed into their bodies, and now it's [...] living off their fears, depression, anxieties."

Stavis is not alone in her beliefs. A 2017 study from Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion noted that 54 percent of Americans "absolutely believe that demons exist." That same study, though, found that believing in demons is one of the "strongest (negative) predictors of mental health."

But in a conversation with Newsweek, Stavis sounded like a normal young woman, cracking jokes about the culture in her native Los Angeles and gently explaining her worldview—which, for most of her life, included demons. She describes her childhood as littered with visions of dark spirits and other images she couldn't explain. They attached themselves to the people around her, feeding off them, she says.

Later, she discovered that entity removal and exorcism is simply something she's good at. Her first exorcism, which she performed on her then-boyfriend at 31, was a rush job. But after she got her footing, she started performing two exorcisms a week. She doesn't consider her skill as an exorcist as exceptional, and she says it certainly doesn't give her any agency over others. She doesn't even charge her clients, making her living writing horror novels and video games instead.

"I never even decided to go public with my exorcisms," she told Newsweek. "Weirdly enough, I was at a Halloween party and someone said, 'Oh hey, here's Rachel, our resident exorcist.' People started asking me questions, naturally, and by the end of the night, an NPR reporter wanted to do a story."

Exorcism is typically connected with Catholicism, thanks to films like The Exorcist. But in that 2015 story, Stavis stressed that her work is non-denominational and as grounded in reality as it can be. "I've never seen the devil," Stavis told NPR. "I don't think Christ compels demons out of the body because some demons probably aren't Christian."

It's an idea she expanded on with Newsweek. "People who immediately think what I do is real tend to be pastors and priests, and many of them are actually comfortable with my point of view," she said. "But, they still have their own processes, ideas that were handed down through so, so many years, so they sometimes have to denounce my work. But I get it. Their belief system doesn't allow for something different to also be true."

Stavis also believes that the entities she drives out of her clients are much, much older than the Catholic church and that these malignant entities don't recognize any organized religion. After all, those human-built structures are relatively new. "Depictions of harmful entities go all the way back to ancient Sumeria," Stavis said. "People have been able to see these things for a very long time."

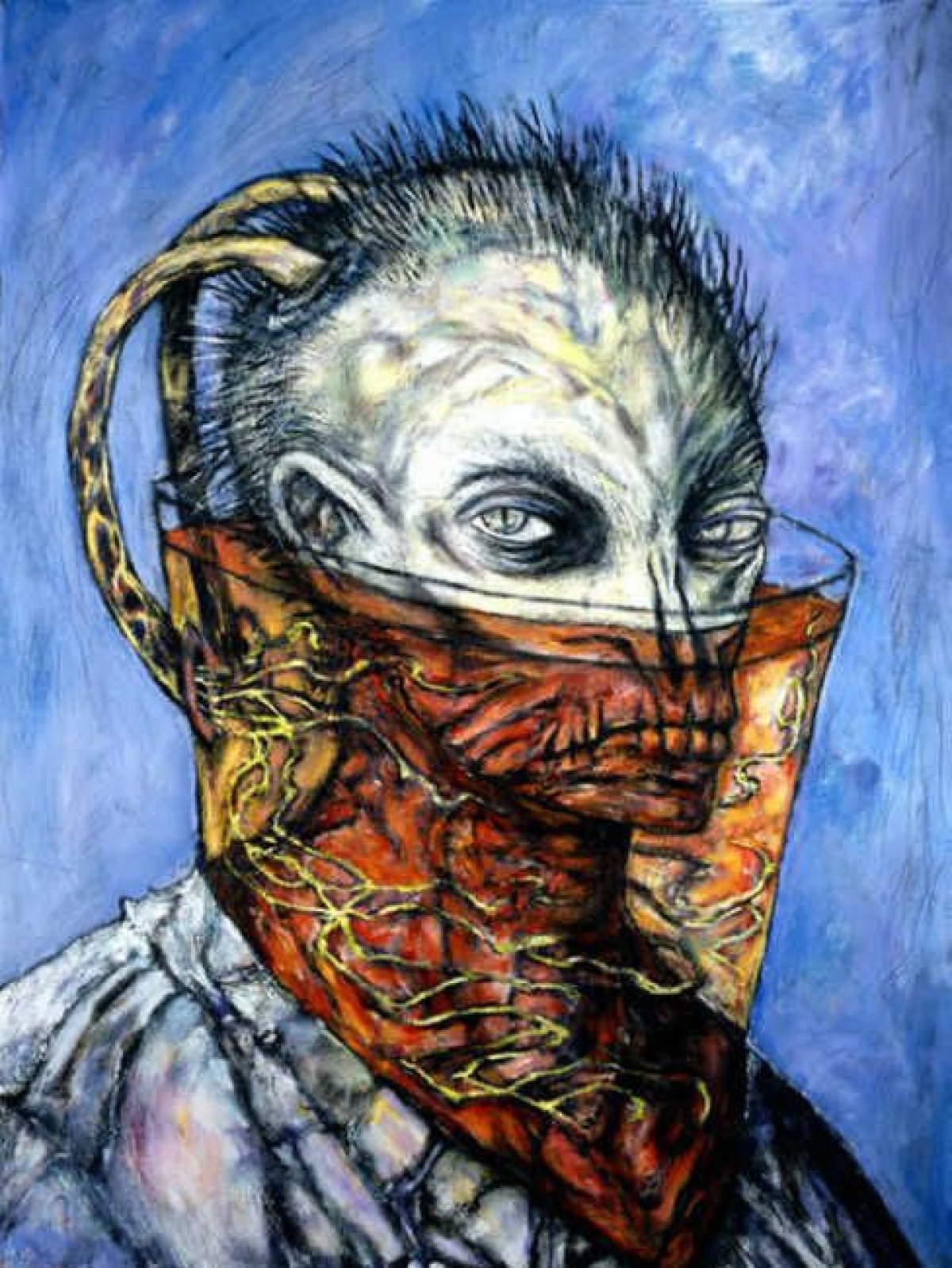

In her book, Stavis outlines a taxonomy of entities she has developed over years of witnessing these creatures hanging off human beings. "The ones I see most often, I call them Clives, because they've always looked like Clive Barker drawings to me," she told Newsweek, referencing the visual artist and director of the 1987 film Hellraiser. "The most common entities are the smaller ones, the things that latch onto you and manifest in dark thoughts that seem to come from nowhere. You're driving, and you suddenly think, 'Run that person over.'"

Stavis said there are larger, more malignant entities in the world, though they're more uncommon.

"Wraiths are attracted to sexuality, so I find that they like victims who were molested or assaulted, or maybe they were exposed to violent sexual imagery too young," she said. And then there are tricksters entities, Stavis says, that use any imagery they can—"maybe as an imaginary friend from childhood or a deceased loved one"—in order to convince their victims to let them hang around in their minds.

"But the most malignant I've ever come across, and this is the type most movies use, are what I call Roamwalkers," she said. "We're talking entities that want to wreak havoc on a global scale. They are exceedingly rare."

That might be why Stavis laughs about how movies portray things like exorcism and entities.

"When you see a demon in a movie, it's also possessing a lone little girl in some middle of nowhere farm town," she said. "Think about it logically: why would a highly intelligent, malignant being pick that victim? What purpose does that serve? Something of that dark nature wants much more power in order to make major, major changes in the world."

With that in mind, it's tempting to start pointing out powerful leaders and public figures who probably have an entity attached to them. But Stavis won't engage in that kind of guessing game.

"This is a very private thing, what I do," she said. "It's not like I'm a medium with good news. Mediums can walk up to people on the street and say, 'Hey, I'm sorry to do this, but I've got a message from your father.' I can't walk up to a stranger and say, 'Listen, I'm pretty sure you were molested, because you have something dark and terrible that's connected itself to you, and I can see it.'"

While she won't approach you to warn you about a demon that has attached itself to you, she does have advice for anyone who thinks they might be dealing with some kind of possession.

It starts with paying attention to yourself. "Every thought, every word, every action of yours has an energy that contributes to that baseline energy," she said. Those who are cruel to others or whose thoughts tend to be self-deprecating are low-frequency people, and they are prime targets for entity possession. "If you're stuck in a low-frequency cycle, thinking, 'I am addicted to something, I hate myself because I'm addicted,' you've trapped yourself in a loop that attracts dark entities," she said.

Stavis isn't opposed to clients being in therapy or taking medication, but there are some entities, she believes, that can't be shaken off by those tactics alone.

"We live in a fear-based culture," she insisted, "and most of us only give ourselves time to react in the moment. What are you putting out in the world? If someone cuts you off on the road, do you get angry? Does that feeling stay long after they've left? If it does, that means you're holding their negative energy for them, and you have to release it. Find a way to be grateful. If it sounds like a cliche, that's because it's the truth."

Stavis's memoir, Sister of Darkness, is available now.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Emily is a culture and entertainment writer living in Manhattan. Previously, she ran the culture section at Inverse and has been published in The Daily ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.