The state of California—its ocean swells, its open spaces, its tech-minded culture—has shaped Yves Béhar. The Swiss-born designer first traveled there with his parents in his early teens, at the beginning of the 1980s. The family took a road trip along the coast, making stops at Hearst Castle, Big Sur and Monterey. A few years later, in his early 20s, Béhar returned to study at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, from which he graduated with a master's degree in 1991. He has remained in the Golden State ever since, running his company, Fuseproject, primarily out of San Francisco for the past 18 years.

"What struck me is, compared to Europe, the amount of space, both physical and mental, on the West Coast," Béhar says, sitting in the lobby of the Royal Palm hotel during the Design Miami fair last fall. Though he turns 50 this May, his rumpled hair and sunny disposition make him seem 10 years younger. "What was truly mind-blowing was how open people were to a Swiss designer with a thick French accent showing up at their doorsteps. I was shy and introverted, and yet people who were leaders in science or technology opened their doors and listened to some of the ideas I had. I began to think that design could be at the forefront of change, not just a sort of skin. It could be profound, about big ideas."

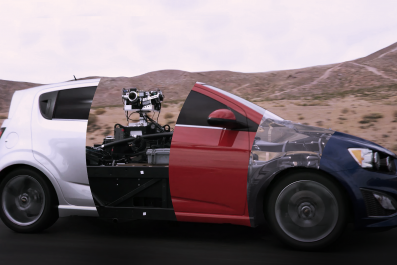

This line of thinking has led Béhar and Fuseproject to create some of the most groundbreaking designs to come out of Silicon Valley in the past two decades—including the One Laptop Per Child XO (2005), a low-cost laptop made for easy delivery to children in developing countries, and the Jawbone Jambox wireless speakers (2011). Béhar has also gained a strong footing in the furniture industry, with a long-running series of collaborations with Herman Miller. Most recently, he has worked with the watchmaker Movado on a line of Swiss-made watches and with Kodak on a revival of its Super 8 home-movie camera. Just a few weeks ago, Fuseproject unveiled its latest innovation, in an exhibition at the Design Museum in London: a prototype for "powered" activity wear that supports movement in elderly people.

More than ever, Béhar says, he's focusing on the connection between health and technology, creating designs that are "life-affirming or life-supporting, not just something that is superfluous or decorative." Architect David Adjaye, a close friend who has shared office space in New York with Fuseproject for years, describes Béhar's approach in an email: "Beyond his deft technical ability, Yves seeks out challenging projects with the potential to empower communities and democratize design. It's rare to find a designer whose creative brilliance is matched by his drive for positive social change."

Growing up in Lausanne, on the edge of Lake Geneva in western Switzerland, Béhar was educated in what he calls a "somewhat conventional" schooling system. In class, his mind often drifted. By his mid-teens, he knew he was not going to follow a traditional path like finance or engineering.

"Since the iPod and the iPhone, design has been fundamental to any business," he says. "What Steve Jobs did is probably the most anyone has done for design. He utilized its power to create entirely new experiences. What I became really passionate about in the late '90s was the fact that design wasn't just specialized. It wasn't just graphic design, or digital or product—you had to create cohesive experiences."

A Design Bridge

Connecting experiences and making the world a more seamless, frictionless place has been one of Béhar's chief motivators. In 1999, when he started Fuseproject, he took on a range of European clients—including Mini Cooper, Birkenstock and fashion designer Hussein Chalayan—who were, he says, interested in knowing "more about how innovation and lifestyle were coming together in San Francisco." Béhar remains a design bridge between international companies and the ideas and technologies percolating out of the Bay Area. "Yves's physical location, who he is as a person and who he has collected as a team—this helps us have a hand that extends into the world of Silicon Valley," says Ben Watson, executive creative director at Herman Miller. "It helps us see what's coming."

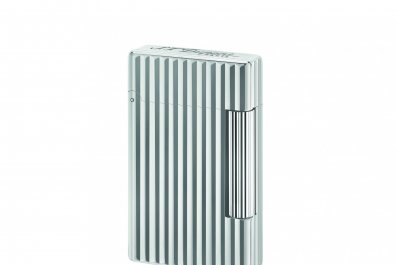

It wasn't until Béhar's 2015 project with Movado—for which he created the Edge line of watches—that he worked with a Swiss company. "There was a joke among journalists that I was the largest Swiss design studio never to work in Switzerland," he says. For the Movado collaboration, he found a company that was willing to push boundaries as well as a mass product—a watch featuring the brand's classic Museum Dial—that was ripe for innovation.

Béhar's solution: to think in 3-D. "Watches are very much still designed from a two-dimensional graphic standpoint," he says. "I wanted to turn that two-dimensional exercise into a three-dimensional one, to create some depth to the watch, allowing light to travel across it." The result is a simple dial with a bold, striking and, thanks to Béhar, signature shape that stands out, even though it doesn't include the brand's name or logo on its face. Efraim Grinberg, CEO of Movado, says he is thrilled with the outcome. "Yves is able to capture the consumer's imagination and really make modern design beauti-ful, and that's not an easy thing to do." Grinberg also says he intends to continue the Movado collaboration—a potential longevity that speaks to Béhar's close relationships with clients.

But of all of these, it's perhaps Béhar's partnership with Herman Miller that most captures the essence of his practice. Fuseproject has worked with the furniture maker for nearly 15 years, creating products such as the energy-efficient LED Leaf Personal Light (2006) and the Y-shaped, full-suspension Sayl office chair (2010). His Public office system (2014) facilitated collaboration between co-workers by allowing them to combine modular units, storage and seating to allow for flexibility and a variety of working environments. Of Public, Watson says, "It wasn't about 'Can I make this one thing 1 percent or 10 per-cent better?' It's a holistic approach to the human experience. Yves is good at deciphering and delivering an experience for human beings that's really thoughtful and pleasant and complete."

A large part of Béhar's success lies in this deep attention to human needs. It's also, in part, because he takes this human-led approach one step further: He views each of his projects like a person. "Each has to be individual, different and original," he says. "You won't be spending much time with someone you consider boring. Objects have to have a personality. They have to deliver a certain amount of expression and authenticity and sincerity about what they do."

In other words, Béhar takes on each project as its own wave. Then, focused and determined, he rides it all the way to shore.

Spencer Bailey is the editor-in-chief of Surface magazine and the editorial director of Surface Media.