Today Nagasaki is a vibrant port city and a hub for fishing, tourism and manufacturing. But on the morning of August 9, 1945, an atomic bomb exploded above the city—a blast so destructive it effectively halved the population of 250,000, killing tens of thousands outright and forcing many others from their homes.

But just hours earlier, a B29 bomber carrying the "Fat Man" plutonium juggernaut was hovering over Kokura—a city at the northern tip of Kyushu island and home to one of the largest arsenals in Japan. Kokura, like Kyoto before it, was the primary target for the blast. But fate—or human guile—spared the city.

Poor visibility forced the B29 "Bockscar" to abandon Kokura on the morning of August 9. "The winds of destiny seemed to favor certain Japanese cities," New York Times reporter William Laurence, a passenger on one of the mission's B-29s, wrote at the time. "We circled about them again and again and found no opening in the thick umbrellas of clouds that covered them."

In 2014, former steelworks employee Satoru Miyashiro told the Japanese newspaper The Mainichi that human intervention was behind the smoke screen. In 1945, he worked at a large steel plant in neighboring Yawata. Fearing an attack that could devastate the city—like the blast that crushed Hiroshima only days before—he told The Mainichi the steelworkers had burned coal tar to produce a thick canopy of black smoke.

It's not clear whether the clouds were the fumes of burning coal tar, smoke from the previous day's firebombing of Yawata, or just bad weather. It may well have been the result of all three.

But by luck or by cunning, Kokura was saved from the devastation of the world's most fearsome weapon.

After giving up on Kokura, Major Charles W. Sweeney flew the Bockscar toward Nagasaki, a city on the west coast of Kyushu. In 1945, Nagasaki was a hub for trade and manufacturing. It was home to several Mitsubishi Heavy Industries plants, including a shipyard, a steelworks and a number of arms factories—one of which produced torpedoes. Hibiki Yamaguchi, a visiting fellow at the Nagasaki University's Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, told Newsweek one of those torpedoes was used in Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Although the atomic bomb exploded in the skies roughly halfway between the Mitsubishi Nagasaki Arms Factory's Ohashi and Mori-Machi plants, Yamaguchi explained this position most likely came down to chance.

Like Kokura, clouds obscured Nagasaki. But Sweeney flew toward a patch of clear sky above the Urakami region, two miles from the planned hypocenter in the densely populated city center. At 11.02 a.m. local time, the Bockscar dropped the most powerful atomic weapon the world had ever seen on Nagasaki.

The "Fat Man" plutonium bomb was far more powerful than the "Little Boy" used on Hiroshima three days earlier. When it exploded, the equivalent of 22 kilotons of power ripped through the Urakami Valley. Although the hills contained some of the blast, it decimated the landscape and killed tens of thousands.

It's impossible to say how many people died that day in Nagasaki, but by the end of the year it was believed that the bomb had killed 75,000—many of them in an instant. Seven decades later, hibakusha—the Japanese name for survivors—are still suffering from the effects of radiation exposure. About 180,000 hibakusha have since perished, Yamaguchi explained.

But all of these numbers are sketchy. The blast wiped out entire families and tore through communities of unregistered migrants, obscuring already patchy records. It's thought that about a third of the city's Korean population of 30,000 people had died. But nobody knows for sure.

The blast didn't just mark the bodies of the hibakusha. In addition to years of psychological trauma, the bomb left invisible but indelible scars. Survivors faced discrimination for years. Some employers refused to hire people from Nagasaki, afraid they might be struck down by debilitating illness.

Women in particular faced intense marriage discrimination. Potential spouses and their families feared hibakusha might give birth to deformed babies, Yamaguchi explained. To this day, even second- and third-generation hibakusha face some discrimination.

"It's not only [atomic bomb survivors] that have been affected in this process of discrimination," he said. "The impact was on the city of Nagasaki as a whole."

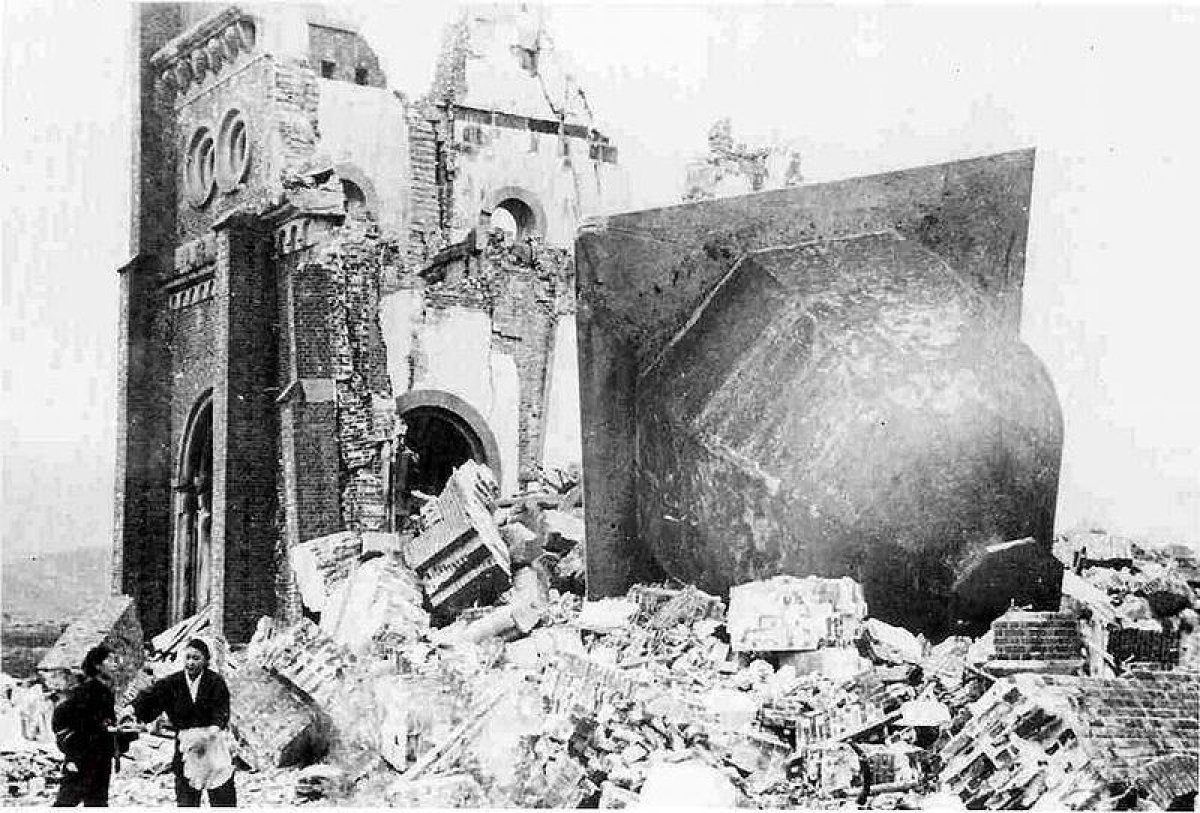

Unusually for Japan, Nagasaki was home to a thriving Catholic population. The city's Catholic history stretches back hundreds of years, to the execution of 26 martyrs in 1549. Between 12,000 and 16,000 Catholics lived in the Urakami District, and they worshipped at Urakami Cathedral. The blast tore through the church, killing Father Saburo Nishida and about 10 parishioners, the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum reported. Between 8,500 and 10,000 Urakami District Catholics died in the blast.

The fallen bell tower of Urakami Cathedral has been preserved at the original site. A replica of the cathedral's entrance is displayed inside the Atomic Bomb Museum.

Today Catholics remember the blast alongside Buddhists and followers of Japan's Shinto religion. They take part in an interfaith mass at Nagasaki Peace Park on the evening of August 8 and march through the city the following night, Yamaguchi explained. On August 9, and throughout the year, survivors tell their stories in an intimate and unremitting campaign against nuclear weapons.

The atomic bomb destroyed the Nagasaki Medical College, which stood 600 yards from ground zero. It killed some 900 professors, doctors, nurses, faculty members and students. Medical research on the long-term effects of the bombing has always been at the core of the present Nagasaki University, Yamaguchi said. Seven years ago, the university opened a department to research the bomb from the viewpoint of social sciences. Today the university sends students as youth delegates to the United Nation's Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference.

Both Nagasaki and Kokura are now part of much larger cities. In 1963, Kitakyushu absorbed Kokura and Yawata. Nagasaki merged with a number of surrounding towns in 2005. About 430,000 people live in today's Nagasaki, and almost a million in Kitakyushu.

Both cities benefited from a postwar economic boom. It took many years to rebuild Nagasaki into a hub for fishing, ship-building and tourism. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is still a prominent city employer, but its old torpedo factory, the Mitsubishi Weapons Sumiyoshi Tunnel Factory, is now a museum.

Kitakyushu's steel industry boomed during the 1960s, and the city was famous for its polluted waters. Now it's something of a green hub, Ian Ruxton, a professor of English at Kyushu Institute of Technology, told Newsweek. Once called the "Sea of Death," Kitakyushu's Dokai bay is thriving. The Yawata steelworks still exist, but the city's now known for its green technologies, software and robotics companies. Like much of Japan, it's struggling with an aging population.

Kitakyushu's residents are well aware of their city's escape, Ruxton said. Today the luck of Kokura and the devastation of Nagasaki are commemorated with a monument in Katsuyama park near City Hall, Ruxton said. A sculpture, a plaque and a bell serve to remind visitors of the devastation faced by Nagasaki that August morning. The bell is a replica of one donated to Kitakyushu by Nagasaki.

The plaque reads in Japanese: "There was a former army barracks in this area. An American military aircraft carrying an atomic bomb flew over to bomb it, however, they turned around and dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki instead as they could not locate the target through the clouds.

"This memorial plaque symbolizes the sincere prayers for all the losses and casualties suffered due to the bombing."

This article has been corrected to reflect the timing of an annual Nagasaki memorial service and march.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Katherine Hignett is a reporter based in London. She currently covers current affairs, health and science. Prior to joining Newsweek ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.