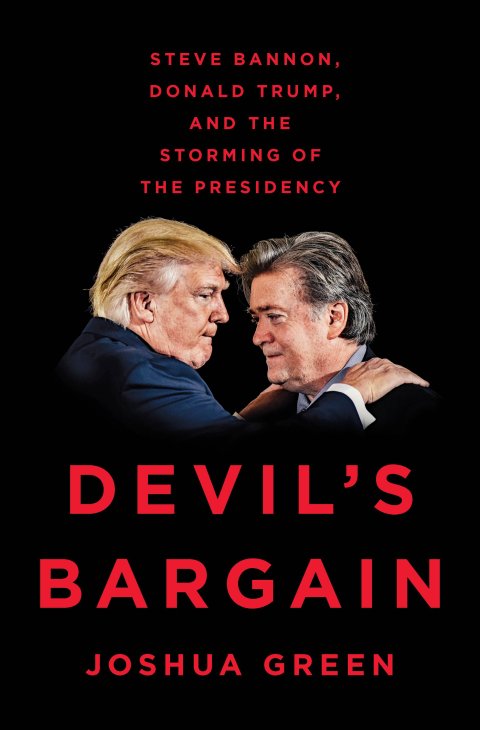

Two things must be said about Devil's Bargain, Joshua Green's new book about chief White House political strategist Stephen K. Bannon: (1) It is not especially good. (2) You won't be able to put it down. I certainly couldn't, surrendering a weekend I should have rightly spent with the kids. I spent it instead with a 63-year-old nationalist whom Time magazine all but called the shadow President of the United States.

Devil's Bargain (Penguin Press $27) is based on a prescient story Green wrote for Bloomberg Businessweek in 2015: "This Man Is the Most Dangerous Political Operative in America: Steve Bannon runs the new vast right-wing conspiracy—and he wants to take down both Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush." The title must have seemed ridiculous back then, when many were wondering what we'd be calling Bill Clinton a few months later. First dude?

At the time, Bannon was the chairman of Breitbart News, the alt-right site that would eventually help clear away Trump's 16 Republican competitors like so much dry brush. Green interviewed Bannon and his associates for what he says was 20 hours of tape. He talked to Trump, too: "a wide-ranging 90-minute interview in his Trump Tower office" (is Trump capable of a conversation that isn't "wide-ranging"?).

This is the stuff book deals are made of, especially at a time when, for so many, consumption of political news is the intellectual version of stress eating. Devil's Bargain, written in obvious haste (the afterward is dated June 5, 2017), is more synthesis than analysis, and the outline of Bannon's strange career is neither illuminating nor useful; it can be summed up in about a dozen words: Virginia, Catholic military school, Virginia Tech, the Navy, Harvard, Wall Street, Hollywood, Breitbart, Trump.

Green's biggest mistake is that he succumbs to a reductively deterministic version of history. His thesis: that Bannon was always fated to become Trump's third and most effective campaign manager, the one who shaped the addled candidate's grievances in a furious—if delusive—nationalism. Writing of Bannon's education at a conservative

Catholic military academy, he approvingly quotes a friend from that time: "There's really no jump at all from Steve Bannon at Benedictine in 1972 to 2016 and Donald Trump."

Bannon's professional career was peripatetic, its biggest success the 1993 acquisition of a stake in the TV show Seinfeld. More illuminating is Bannon's foray into online gaming, via the Internet Gaming Entertainment, a concern based in Hong Kong. The company, a marketplace within World of Warcraft, revealed to Bannon that the Internet was "populated by millions of intense young men," as Green writes. "While perhaps not social adepts, they were smart, focused, relatively wealthy, and highly motivated about the issues that mattered to them."

Green is most insightful writing about Bannon at the helm of Breitbart News, a role he assumed after the site's founder, Andrew Breitbart, died in 2012. He credits Bannon with hiring Milo Yiannopoulos, the mediagenic British provocateur who attracted to Breitbart the very gamers Bannon had marvelled at years before. "I realized Milo could connect with these kids right away. You can activate that army." It's an army recently seen waging a "meme war" against CNN.

More substantive than the hiring of MILO, as he is known on Breitbart, was Bannon's founding of the Government Accountability Institute, a think-tank essentially intended solely to fund the research of conservative writer Peter Schweizer. The fruit of that research was Clinton Cash: The Untold Story of How and Why Foreign Governments and Businesses Helped Make Bill and Hillary Rich, published in 2015.

Bannon's genius was to pitch the disputed but troubling revelations in Clinton Cash to the mainstream media, not to right-wing outlets still hot on the trail of Whitewater. He needed to win the credibility of The New York Times, not of World Net Daily. "Anchor left, pivot right," said a GAI researcher. It worked, with both the Washington Post and the Times writing about Schweizer's damaging findings. "We've got the fifteen best investigative reporters at the fifteen best newspapers in the country all chasing after Hillary Clinton," Bannon said.

There are some curious omissions in Devil's Bargain, most notably about Bannon's personal life. In 1996, his second wife called the police in Santa Monica because, she charged, "he pulled at her neck and wrist during an altercation over their finances," according to a Politico report. In 2007, in documents relating to custody of their two daughters, she also accused Bannon of anti-Semitism. "He said he doesn't like Jews and that he doesn't like the way they raise their kids to be 'whiney brats,'" the filing said. In a 2016 radio interview, he lamented the prevalence of Asian-born executives in Silicon Valley.

Bannon's no easier on women. Consider the disparaging remarks he made about a female executive when he was working at the Bisophere 2 project in 1993. In documents obtained by BuzzFeed, he vowed to take comments the "bimbo" had made about safety at the Arizona research facility and "ram it down her fucking throat." Or consider a 2011 radio interview, in which Bannon referred to women educated at elite Northeastern colleges as "a bunch of dykes."

Should these incidents and allegations define Bannon? Perhaps not. But they deserve mention, especially in a book devoted in good part to the art of the smear.

Bannon became Trump's campaign manager in August 2016, largely at the behest of the powerful Mercer family, which funds right-wing causes (including Breitbart). Some conservatives thought the hiring was a coup de grâce for Trump's chances in November. Green quotes the conservative commentator Rick Wilson: "If you were looking for a tone or pivot, Bannon will pivot you in a dark, racist, divisive direction.... Republicans should run away."

They didn't, it worked, and this is a case that Green makes persuasively: that Trump's win is largely due to Bannon using the candidate as the vessel for his nationalist ideas. He recounts an episode from late in the election, when some accused Trump's campaign of running a TV ad rife with anti-Semitic insinuation. Many were disgusted. Bannon was unfazed. "Darkness is good," he told the man who would be president. "Don't let up."

In due time, the Age of Trump will find its Hunter S. Thompson, but it might be years before anyone has the necessary distance to capture the competing currents that daily buffet the political landscape like furious storms over the face of Mars. Devil's Bargain is not that book, yet it is addictive. Think of it, then, as a not especially healthful handful of deep-fried morsels. You could do much worse, and if you're on social media, you almost certainly have. Snack away.