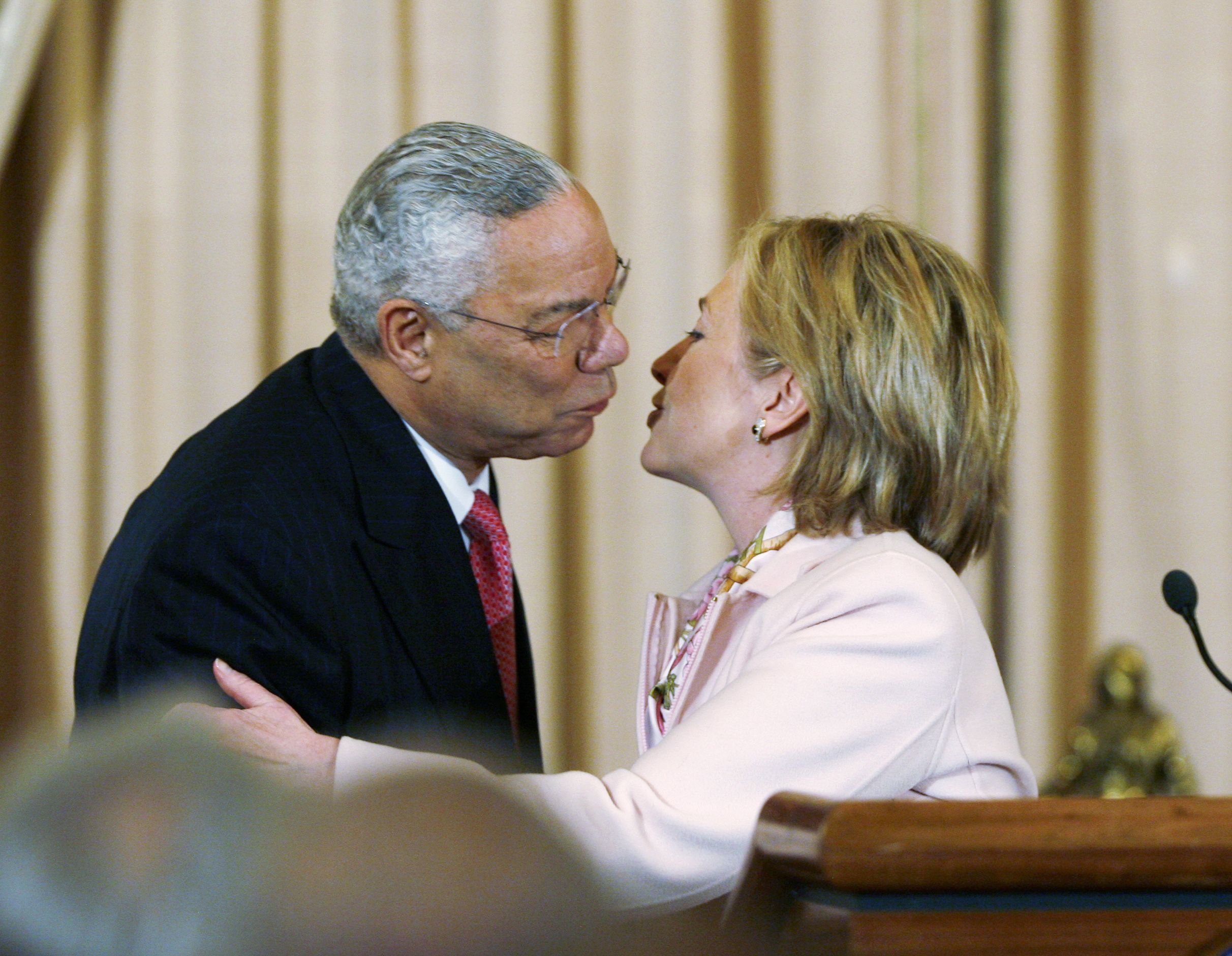

Did Colin Powell suggest that Hillary Clinton should use her private email account as secretary of state—as he had admittedly done in that same job several years earlier?

Last week, The New York Times confirmed that Powell did offer her precisely that advice, based on an account in my forthcoming book on Bill Clinton's post-presidency. Yet Powell has responded by insisting that he has "no recollection" of such an incident.

In Man of the World: The Further Endeavors of Bill Clinton, to be published in September by Simon & Schuster, I report on a dinner party that former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright hosted for Hillary Clinton several months after she assumed that office in 2009, with Powell in attendance:

Toward the end of the evening, over dessert, Albright asked all of the former secretaries to offer one salient bit of counsel [to Clinton].... Powell suggested that she use her own email, as he had done, except for classified communications, which he had sent and received via a State Department computer on his desk. Saying that his use of personal email had been transformative for the department, Powell thus confirmed a decision she had made months earlier.

Following up on my book, which the Times received in advance of publication, reporter Amy Chozick discovered that Clinton had mentioned her conversation with Powell—as well as an email exchange with him on the same matter—when the FBI interviewed the Democratic presidential nominee during its probe of her private email use at the State Department.

Powell's office then released a statement saying he "has no recollection of the dinner conversation," which he has since repeated to other news outlets. While hardly a denial, his response seems designed to cast doubt on the story.

Over the weekend, he told a reporter for the New York Post's Page Six, "Her people have been trying to pin it on me," with evident annoyance. "The truth is she was using [her personal email] for a year before I sent her a memo telling her what I did," he said.

But last June, while reporting on Powell's advice to Clinton for my book, I contacted his office for comment—and got a very different answer.

His principal assistant, Margaret "Peggy" Cifrino, informed me then via email that their calendar showed that the Albright dinner had occurred in June 2009. While he didn't recall some details of the dinner because it had occurred seven years ago, according to Cifrino, he remembered what he did and didn't say to Clinton on the topic in question that evening:

He does recall sharing with Secretary Clinton his use of his email account and how useful it was and transformative for the Department. He knew nothing then or until recently about her private home server and a personal domain, nor, therefore, could he have advised her on that or suggested it. By June I would assume her email system was already set up.

So it is perplexing for him to say he doesn't remember that dinner conversation at all now, since, according to his own assistant, he remembered at least some of what he said as recently as two months ago.

Yet in another sense, it is hardly surprising that Powell would prefer not to be drawn into the center of the continuing controversy over Clinton's emails, a position he has carefully avoided so far.

After all, not only did Powell use a private account to communicate with his State Department subordinates and others, like Clinton—but unlike her, he failed to provide any of those email records to the National Archives, which requested all of the former secretaries of state to turn over electronic records related to their government service.

Moreover, several indignant Clinton critics have drawn a distinction between her use of private email accounts and his, noting that she used a server located at her Chappaqua home, while he used America Online—suggesting that what Powell did was somehow more virtuous, circumspect or secure.

But as Powell knows all too well, the Romanian hacker known as "Guccifer," whose real name is Marcel Lehel Lazar, easily invaded his highly vulnerable AOL account and stole messages that he later posted on the Internet. When the Justice Department prosecuted Lazar, Powell was one of the "victims" included in the indictment.

Contrary to claims made by Lazar and others, however, there is no proof that Clinton's email was ever successfully hacked. (In fact, Guccifer eventually confessed that he had lied about accessing her account.)

Powell's complaint that Clinton is trying to "pin" her email use on him also seems misplaced. Although several sources told me about Powell's 2009 conversation with her, Clinton was not among them.

She didn't mention Powell when I interviewed her for my book in 2013, and during the past seven years she has never spoken publicly about his advice, which she considered private. Although she told FBI agents about it earlier this year, she had every reason to expect that interview would remain confidential.

To "blame" Powell could not have exculpated her in any case—and she has taken responsibility for her own decision, which she has described more than once as a mistake that she is sorry for making.

Finally, although Clinton provided 55,000 pages of emails to the National Archives, Powell has said that all of the email messages he sent as secretary of state are long gone, in apparent violation of his responsibility to preserve them under the Federal Records Act.

That is too bad for historians and everyone else who would like to know more about Powell's conduct during the prelude to the invasion of Iraq—among many other controversial events during his tenure.

Joe Conason is editor-in-chief of The National Memo. His Man of the World: The Further Endeavors of Bill Clinton, is published in September by Simon & Schuster.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.