The historian Kim Phillips-Fein agreed to meet at the Grand Hyatt New York hotel on 42nd Street on a sweltering Manhattan afternoon that rendered the air a thick gray soup. The building was air-conditioned but otherwise a monstrosity, made uglier by the fact that it stands next to the Beaux Arts masterpiece that is Grand Central Station. In the atrium, which resembled a mausoleum, we found an uncomfortable marble perch where we could sit unperturbed.

"These big marble heads," Phillips-Fein said in reference to some giant, artless statues in a fountain. "What is going on with them exactly?" she wondered, the derision compounded by her native Brooklyn accent.

The man who would presumably know that answer now sits in the White House. Until 1976, the site where today the inglorious Grand Hyatt stands belonged to the Commodore Hotel. As Phillips-Fein writes in her sharp and necessary new book, Fear City: New York's Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics, Trump strong-armed a City Hall desperate to attract investment for New York into giving him a tax break in return for redeveloping the decrepit property. Thus the hideous, outsized building, with its ersatz shows of status. And the huge heads.

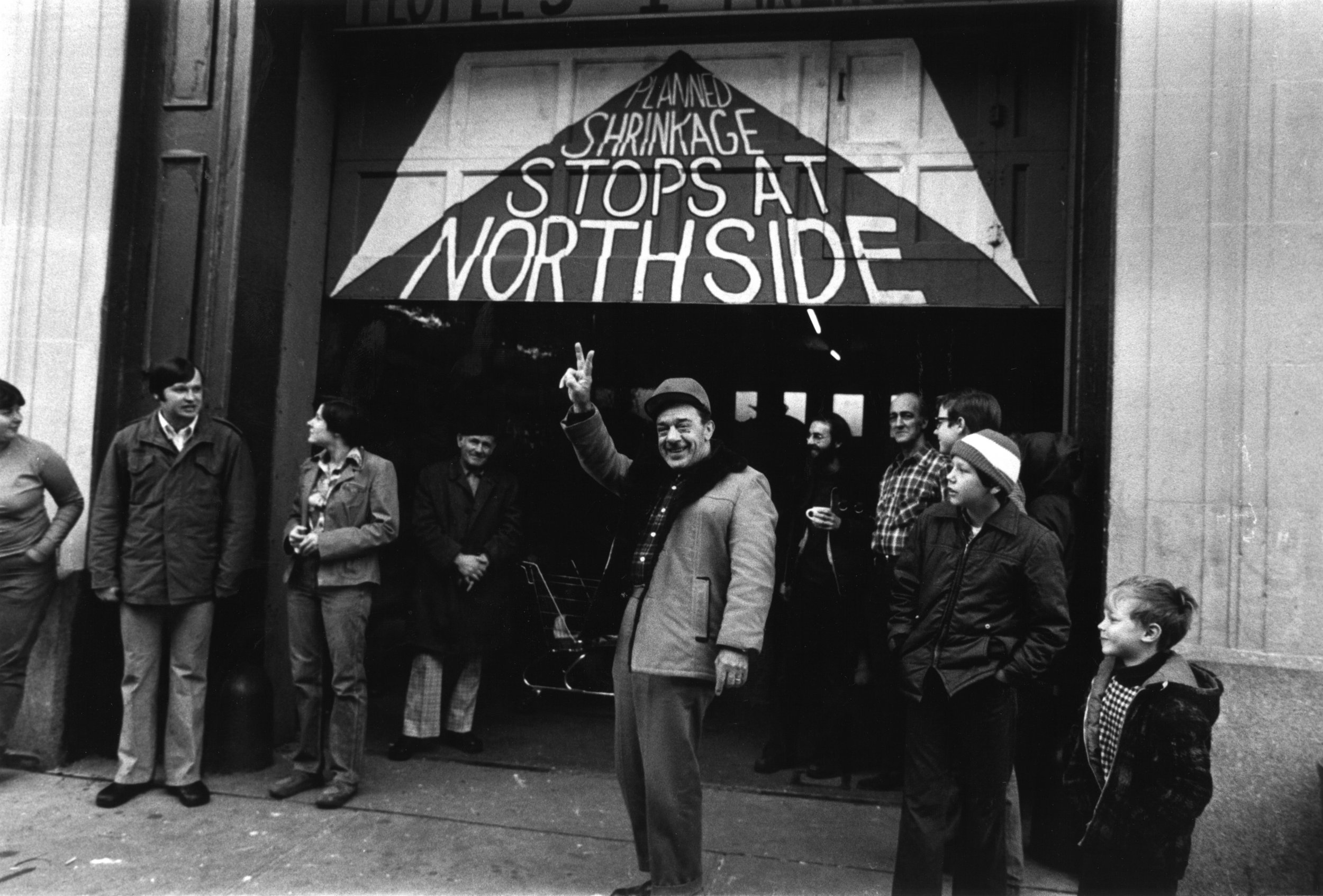

This wasn't just the entree of an outer-borough mogul-in-training into Manhattan real estate; rather, Phillips-Fein argues, something bigger was afoot. "In the late 1970s, even as most middle- and working-class New Yorkers were finding it more difficult to live in their city, a glittering new world of wealth was starting to take shape," she writes in her book. "Throughout Manhattan, new buildings were going up, designed to cater to the city's elites—and, indeed, to elites from around the world who might be enticed to come over." The city of writers and longshoremen, painters and seamstresses, was becoming the city of Donald Trumps and Gordon Gekkos. Those in power wanted it that way. Many still do, four decades later.

Nominally, Fear City is about the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975, brought about by reckless spending by liberal Republican mayor John V. Lindsay, who'd hoped to one day be president, and decades of shoddy accounting that left the city's finances an indecipherable mess. There was an eventual $2.3 loan bailout by President Ford, though not before he was shamed by the Daily News in a headline—"Ford to City: Drop Dead"—that is among the most famous in journalism.

Phillips-Fein is excellent in her grasp of details, recounting that time's iconic fights, like the one over tuition at City College, and capably depicting the city leaders who both ruined and revived New York. Especially worthwhile is the detailed portrait of Mayor Abe Beame, who is often eclipsed by the much bigger, flashier personalities of his predecessor Lindsay, and Lindsay's tormentor, four-term New York governor Nelson D. Rockefeller.

But what is truly original here is Phillips-Fein's conclusion, which is that the city committed civic suicide by turning away from the social safety-net programs championed by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and beloved by generations of middle-class New Yorkers.

The lesson of 1975, for many, was that only business, and business people, could save New York. "Many people in the conservative movement of the late Seventies saw New York and its failure as a failure of liberalism in microcosm," Phillips-Fein told me. She is a professor of history at New York University whose previous book was Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Against the New Deal. The transformation of New York after its rescue (not only by the federal government, but by the city's business leaders, most notably the banker Felix Rohatyn) was the culmination of that corporatist crusade.

Fear City takes its title from a grotesquely frightening pamphlet officers of the New York Police Department handed out at airports, as a sort of public relations battle in the face of cuts to their department. The city was crime-ridden and decrepit, and Phillips-Fein is sensitive to charges that she is romanticizing some of New York's darkest days. Her book is likely to find acute resonance with those who remember when the West Village was affordable and 57th Street wasn't a refuge for foreign kleptocrats squirreling away their ill-gotten gains in glass towers.

Others, though, have praised Phillips-Fein's scholarship without embracing her conclusions. In the New York Times Book Review, Jonathan Mahler, who has written a history of New York's deterioration in the 1970s, The Bronx Is Burning, argued that she provides "a clear sense of what was lost as New York left behind one set of priorities and embraced another" but doesn't offer an alternative. Would it be better if New York today looked less like London than Detroit? Some may argue that, but not many.

The urbanist Julia Vitullo-Martin was more harsh in her assessment, writing in The Wall Street Journal —the first read of many of the business elites to whom the city now inarguably belongs—that Phillips-Fein "seems not to comprehend that rescuing New York meant restoring the city's economic base." That is, the taxes of the rich will pay for the services of the poor. Nobody else will.

This was the view of the mayors who brought New York back from the brink, Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani in particular. There exists no better sign of their efforts than the intersection of 7th Avenue, Broadway and 42nd Street, otherwise known as Times Square. The peep shows and dive bars are gone, replaced by corporations like Thomson Reuters, not to mention middle-American chain restaurants like Applebee's. Whether that's cause for celebration or lament will in large part inform your views on Phillips-Fein's smartly argumentative book.

No mayor has done more to welcome the rich than Michael R. Bloomberg, who presided over City Hall from 2001 until 2013. "If we could get every billionaire around the world to move here, it would be a godsend," Bloomberg said as his final term was coming to an end. It's no surprise that his successor, the Brooklyn progressive Bill de Blasio, won largely on the strength of his righteous anger at there being two cities, one for the rich, the other for the poor.

Phillips-Fein is mixed on de Blasio's efforts to restore some of the social benefits the fiscal crises wiped away. She says his universal pre-kindergarten program is a "big deal," the kind of Great Society initiative that signals the city's commitment to the working classes and the poor. "It should be possible, in cities, in this incredibly wealthy country," she tells me, "to build institution that promote social solidarity and give people a sense of belonging to the broader public life."

At the same time, as the title of her own book suggests, the fear of civil disorder is far greater than any collective wish for class or racial comity. This summer will mark the 40th anniversary of the blackout of 1977, during which widespread looting signalled a total breakdown of municipal norms and institutions across the city, from Bushwick to Harlem. Today, the city leaders know they have to avoid another '77, which they can only do by avoiding another '75. That's why, these days, all billionaires are welcome in New York.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.