"I heard a thump. I thought a car had hit a person. I turned around: a girl was lying in the road."—The words of a witness

June 28, 2008, 2:30 p.m. Water Street, the corner of Wall Street, in Manhattan. A headache-making-hot, New York high summer. A Saturday, the bankers are away, the street is empty—apart from the dead girl in the middle of the road. Police report the deceased is a Russian supermodel. Ruslana Korshunova. "Her death is a suspected suicide by jumping from the building site next to her ninth-floor apartment. No signs of a struggle detected. No alcohol or drugs in her blood or urine. She left no note. She was 20. She landed 8.5 meters from the building."

8.5 meters? That's not a fall. That's a leap. That's almost flight. The supermodel didn't stand on the ledge and take a step off. The supermodel took a run and soared.

There are models and there are models. There are the lanky androgynous clones, the perfect coat hangers for catwalk collections. And then there are the Ruslanas. The ones who stand out. Their proportions are not perfect, their catwalk work limited, but they become the faces that define a product. Ruslana was famous for being the face of a "magical, enchanting perfume" by Nina Ricci. You might remember the ad. It's in the style of a fairy tale. Ruslana, in a pink ball gown with bouncing curls and wonder-filled eyes, enters a palace room. She gasps with teen excitement: in front of her a magical tree, at the top a glistening pink apple. She climbs the tree, reaches for the apple…

Ruslana seemed to have everything. Why this dismal end? The answer to that question would lead me on a three-year journey, as I researched material for a documentary, through New York, London, Milan, Kiev, and Moscow, into the life of that shiny, lonely tribe: the world's top models. On the way I found more deaths among Ruslana's friends, more attempted suicides, until ultimately I arrived at the most unlikely of destinations in the former evil empire.

Water Street is at the tip of the Financial District, where office blocks meet the East River. In the evenings it's dead, just clerks in pall-bearer black suits hurrying home. Ruslana's apartment is a rare residential building on the street. Few families live here, just the tired foot soldiers of globalization: a Central Asian wool trader, a Malaysian Ph.D. student. Jobbing models hand the place down to each other. Ruslana was the last. There are few personal belongings in Ruslana's rented rooms. The Egyptian porter remembers that she traveled all the time, never had a proper home.

Ruslana's journey ended here. Where had it begun?

Tatyana is a modeling scout. She sees thousands of girls a year; maybe three will make it to the top. The former Soviet Union is her territory. More than 50 percent of the world's top models are from the region: many girls see it as their best chance for a decent life. In 2005 Tatyana was flying home from a beauty pageant in Almaty, Kazakhstan. She had seen no girls of note, a disappointing trip. She flicked through the in-flight magazine, browsed through a random article about Amazons. And then she stopped. A photo of a girl. Amazing. The photo itself was in dubious taste: a semiclad waif in tribal garb, posing like some cross between Lolita and Mowgli in a jungle of plastic trees. But the girl herself—she was amazing. Her blue gaze went on forever, so powerful and deep that everything, Tatyana, the plane, the clouds, seemed to be caught inside it: small toys suspended inside this young girl's gaze. Wolflike, she stared out from her Siberian ancestry: the taiga, Baikal, snowy wastes.

Tatyana had visited every modeling agency in Almaty—how could she have missed her? It turned out Ruslana wasn't a model, but a friend of a friend of the editor. They'd taken the photos for fun. Ruslana was 17, went to one of the best schools in Almaty, spoke fluent German, and dreamed of a place at a European university. She was called to a casting in London. Her mother, a manager at a cosmetics company, didn't want to let her daughter go. Ruslana insisted: "London! I'll finally see London!"

At the offices of Ruslana's first agency I find video of that trip to London. A teenager—no, child—in a hoodie on a blustery London day, snapping photos of Tower Bridge, grinning goofily, laughing widely, and trying to hide her braces as she does so. Then she takes the hoodie off, and down it tumbles: that heavy, golden, knee-length hair. They nicknamed her the Russian Rapunzel in modeling land. Before her trip to London, Ruslana had never washed her own hair before—her mother had always helped her. Now she was staying in packed model flats in Paris and Milan, her days a procession of castings. Her life reduced to measurements (32-23-33), rooms full of tense girls eyeing each other's legs-hips-breasts, desperate to be the one who's picked: every rejection a slap saying your body's wrong, that you're wrong. Friends remember that Ruslana would cry—she took rejection personally, missed home. Around her swirled a whirlpool of cocaine, champagne, debauchery. Many girls get sucked in. Ruslana was different. She would go to bed early and wrote poems to console herself, posting them on social-networking sites:

"Instead of moaning at the thorns/I'm happy that a rose among them grows."

Then came the Nina Ricci ad. The magical tree. The pink apple. Stardom.

That ad took Ruslana from the world of wannabes to the best parties in New York, trips to convicted pedophile Jeffrey Epstein's private island, to Moscow where the Russian mega-rich were keen to meet the beauty from the ad, and where she fell blissfully, childishly in love with one of the handsomest tycoons in town.

In Moscow, I seek out Luba, Ruslana's friend and colleague, who was close to her in Moscow around that time. Luba's flat is stuffed with hundreds of cuddly toys. They're nothing like their images on paper, these girls. They're small, scared, brittle. When the camera zooms tight, you notice their wounded eyes, both searching for guidance and mistrustful. Luba remembers Ruslana's lover well: "He's gorgeous. Girls drop at his feet. He's been with so many of my friends. All of them perfect." Friends, more experienced girls like Luba, warned Ruslana not to fall in love. But she was certain this was the real thing. She wanted marriage, children, a steady home. "That was the thing about Ruslana—there was something childish about her. She believed."

When the tycoon dumped Ruslana, she kept on texting him, hoping for an answer. She posted poems of unrequited love on her networking page:

"You left again, leaving in return/A castle of pink dreams and ruined walls … it feels as if someone tore out my heart and trod all over it."

Friends recall that the tycoon's personal assistant called Ruslana and ordered her to leave him alone. And as suddenly as he had dumped her, her career stalled, too. "She couldn't understand," Luba says. "Suddenly she was one of a thousand girls. One of a million. A no one."

So was it all that simple? Just a girl caught up in her emotions? Sucked in and tossed out by an uncaring industry? It's a scenario many models face. Elena Obukhova attempted suicide after two years working in Milan; she is now a psychologist planning to set up a counseling center in Moscow aimed exclusively at models. "You're in a world where nothing is real. You're paid to be always on show. Men sleep with the girl in the photograph, not with you. But your feelings are genuine. At one point I just couldn't tell who I was anymore: me or the image I was modeling. And in a weird way, the only way I felt I could be real again was to attempt suicide."

But Ruslana's friends and family all reject the idea that love and career were the cause of her demise. Modeling had never been more than a means to an end for her: she was planning to enroll at university. She was over the tycoon by the time of her death—there were new lovers on the horizon. They suspect foul play, that the case was closed too quickly: How did she manage to jump 8.5 meters? She wrote incessantly—why no note? She'd hinted at conflicts over money, but never said with whom. Was she being forced into something she didn't want to do?

Samples of Ruslana's remains are kept in a beaker in an underground vault at the New York Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. The family orders bits of blood and flesh, hoping toxicology and histology tests will give fresh clues.

A year passes from Ruslana's death. I get a call. Another model has killed herself, this time in Kiev, Ukraine. She is Ruslana's friend.

Luba, Ruslana's confidante from her Moscow days, knew both girls well. She chain-smokes backstage at Moscow's fashion week; I persuade the organizers to let me film there by pretending I'm shooting a glamorous portrait of the fashion industry. Conversation is difficult, and we talk in between her walks onstage. She whispers scared before gathering herself for the flashbulbs and fashionistas: "First Ruslana, now Anastasia. I'm wondering which of my friends will be next."

I sit with Olga, the mother of the second girl, in a Kiev café. She's slight, a former ballerina. She is trembling; the grief seems to blow through her like a wind. A waitress takes our orders, the process torturous: how to decide whether you want extra cream when you've just lost your daughter?

"I got home late. She wasn't there. I found a note: 'Forgive me for everything. Cremate me.' I ran to the police station. A cop said casually: 'You the mother of that girl who threw herself from the block of flats?' I didn't know what to say. They showed me a bag with [sneakers]. They were hers. Then there could be no doubt."

Anastasia Drozdova had grown up with her mother in single-roomed dormitories, moving from one provincial ballet to the next. Olga had wanted her daughter to follow in her steps and become a ballerina. But Anastasia was too rangy for the quick precision of classical ballet. In the blotchy home video of her dancing lessons, Anastasia is always tripping over herself, dismayed at her own body. But that body was perfect for modeling: she came 14th in Elite Model Look's European competition, third for the whole of the former Soviet Union. She worked all over the world, helped her mother build a proper apartment. Anastasia had a deafening laugh (people would turn around and stare in restaurants), was the live wire at every party. But in the last month before her death she'd changed. She came back down to Kiev from Moscow, where she had been based, refused to leave her room, sat scrunched under a duvet during a 40-degree heat wave.

Olga can't make sense of it.

"I searched her room for clues. I found these papers from somewhere called the Rose of the World. Strange words: 'Anastasia, your lullaby is winter's end. You're on your way.' What could they mean? What is the 'Rose of the World'? I know she went there with Ruslana."

Training for personality development is how the Rose of the World describes itself. "Our seminars will teach you how to realize your goals and achieve material wealth," its website states, lit up by photographs of happy, shiny people. A Moscow friend told Anastasia and Ruslana they should go. Both models were upset by failed love affairs, stalled careers. They paid just under $1,000 for a three-day course and went. What role could these trainings have played in their fates?

The Rose of the World runs its trainings in a Soviet-gothic palace at the All-Russian Exhibition Center (VDNH) in northern Moscow. VDNH was commissioned by Stalin to celebrate Soviet success; now it is rented out to petty traders selling everything from kitsch art to rare flowers. Stray dogs hunt in packs between gargantuan statues of collective-farm girls. The trainings are in a vast building where, in Soviet times, the Komsomol would meet to sing songs of praise to tyrants. I acquire hidden-camera and audio recordings of the training. When you enter the Rose, there is darkness and shouting, everything is designed to stun the conscious mind, suspend critical thought. Then the "life trainer" emerges. He talks so fast you can't help but be confused, the microphone set at a level your head starts hurting.

"In the coming days you will experience discomfort. Fear. But this is good. This is the inner barrier you have to break through."

There are 40 people in the hall, who are asked to confess their worst experiences. Tales of rape, abusive parents. Ruslana, I learn, was the most enthusiastic speaker. She spoke about her father's death, her failed romance—cried publicly, laughed violently. Three days of shouting, recalling repressed memories, meditation followed by dancing, tears followed by ecstasy. Every intense emotion you've ever had, stuffed into three life-changing days.

The models signed up for more training, each one a little more expensive than the last, each one a little more intense. Friends remember that Ruslana and Anastasia thought they had finally found a place where they could be themselves, where people seemed to care about their inner turmoil, not their images on paper. But could they have been sucked into the cruelest illusion yet?

The Rose's website reveals its trainings are based on a discipline called Lifespring, once popular in the U.S. What the site doesn't mention are the lawsuits brought against Lifespring by former adherents for mental damage, cases that caused the U.S. part of the organization to shut down in 1980. In Russia, Lifespring is in vogue, filling in the post-Soviet spiritual vacuum, providing "life-changing" and "transformational" experiences without the inconvenience of traditional religious moral codes. A Lifespring-inspired trainer has even had his own show on the country's main television station.

After several months at the Rose, friends of Ruslana and Anastasia began to notice changes in their behavior. Anastasia would start rows, then burst into tears. She missed castings, became reclusive. Ruslana became aggressive, for the first time ever swore and cursed. Both lost weight. Volodya, a true believer who works as an assistant at the Rose, claims this is normal: "Ruslana had what we call a 'rollback.' She felt a little strange. You'd find her wandering round town, unsure what she was doing there. Maybe she'd cry at night. But she couldn't have killed herself. We cured her of any problems she might have. And Anastasia? She was messed up already. We tried to help her, we really tried. But she refused transformation. Blame modeling, maybe drugs, not us."

Experts think differently. In New Jersey I visit Rick Ross, head of the Cult Education Forum, a nonprofit group devoted to research into cults: "These organizations never blame themselves. They always say, 'It's the victim's fault.' They work like drugs: giving you peak experiences, their adherents always coming back for more. The serious problems start when people leave. The trainings have become their lives—they come back to emptiness. The sensitive ones break."

Young women from the former Soviet bloc are particularly fragile. Six of the top seven countries worldwide for suicide rates among young females are former Soviet republics: Russia is sixth in the list, Kazakhstan second. The sociologist Emile Durkheim argued that suicide viruses occur at civilizational breaks, when the parents have no traditions, no value systems to pass on to their children. Thus there is no deep-lying ideology to support them when they are under emotional stress. Ruslana's and Anastasia's parents were brought up in the Soviet Union; their children lived in a completely different world.

Anastasia spent almost a year attending trainings at the Rose. A few months after her final sessions, she broke down completely. Ruslana was there three months. Then she returned to New York to look for work. At that time she wrote: "I'm so lost, will I ever find myself?" That was a few months before the end.

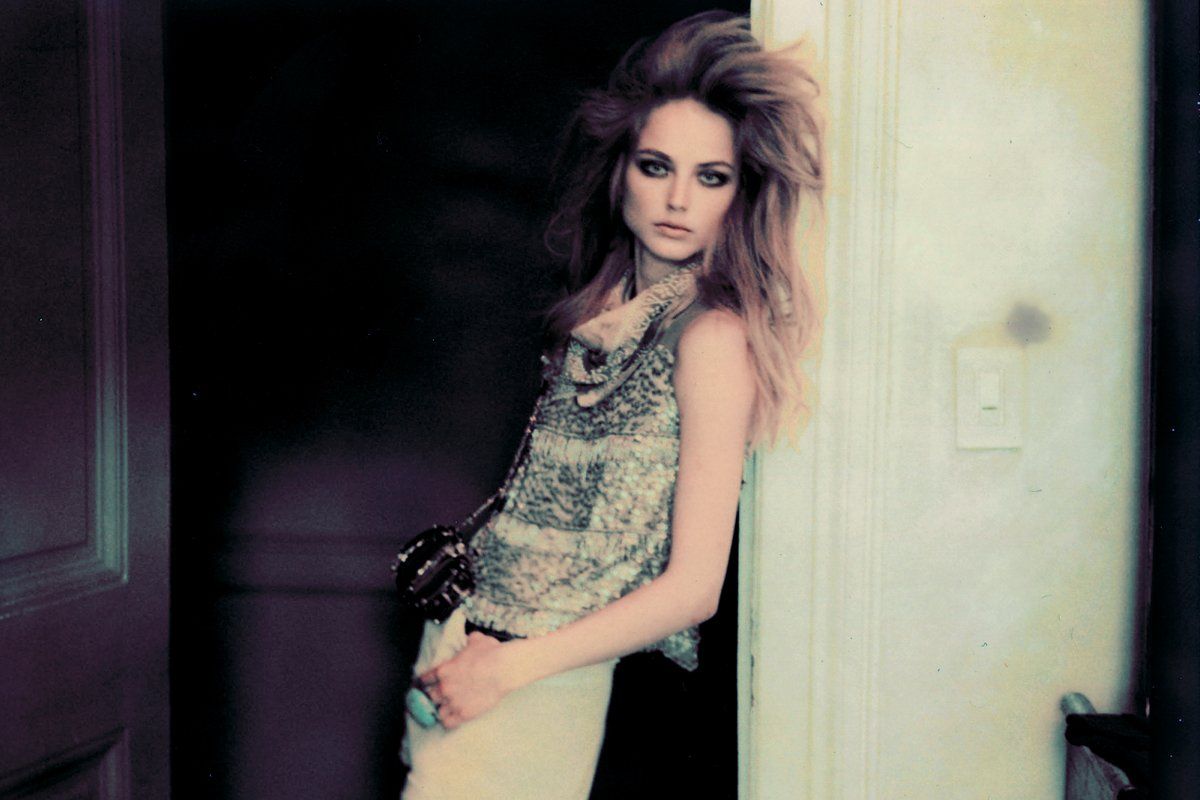

June 27, 2008. One day before her death, Ruslana starred in a photo shoot on a roof in midtown New York. A weird day: first rain, then sun so hot the camera burns. The photographer's name is Erik Heck. He shows me grainy 8mm video of Ruslana's last day. The Ruslana we see in this shoot is completely different from her previous work. She's a grown woman, not a fairy-tale princess. For the first time I catch a glimpse of the real person. "She'd always been told to play different roles, to be a bubbly teenager. What I saw in her was more than that, a timeless beauty," Heck says. "I shot her when she wasn't watching, she had no time to pose. That's when you get the best work. She was free."

A day later she was dead, three days before her 21st birthday. Ruslana's friends and relatives are still convinced she was murdered. All the pathology tests have proven nothing new, but every report leaves enough space for speculation.

More than two years after her death, the Nina Ricci ad with Ruslana was still employed in Russia, her face hanging over Moscow with "a promise of enchantment." The perfume is a hit with teens. It smells of seductive, adult musk, mixed with childhood scents of toffee apples and vanilla.

Pomerantsev is a television producer and nonfiction writer.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.