Updated | When a Tunisian street vendor set himself alight in a small town in December 2010, no one could have predicted what would come next: protests across the Arab world, riots that toppled dictators, and civil wars that still rage today. At the time, Moises Saman, an American-Spanish photographer and member of Magnum Photos, accepted a New York Times assignment to go to Tunisia in 2011, thinking the unrest wouldn't last long. After almost seven years working in Iraq and other countries in the region, Saman was ready for a change and had plans to move to Latin America.

Those plans never materialized. Instead, Saman's assignment in Tunis marked the beginning of a four-year journey documenting the upheaval of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Libya, Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt—where he moved soon after the revolution and stayed for three years. Saman had already worked in several conflict zones, including Afghanistan, Iraq and the Balkans, forging a successful career as one of the leading documentary photographers of his generation. But the Arab Spring felt different because of its sheer pace.

"I was going from one assignment to another, from one revolution to the next, without really seeing the big picture," says Saman, who now lives in Barcelona, Spain with his fiancée. "I was working one week in Tunisia, the next week in Egypt, and two weeks later I was in Aleppo. I didn't really have the luxury of much perspective—not that there was necessarily any to be had. The situations were so complex. I just felt the need to sort of slow down and take a look at what I had done."

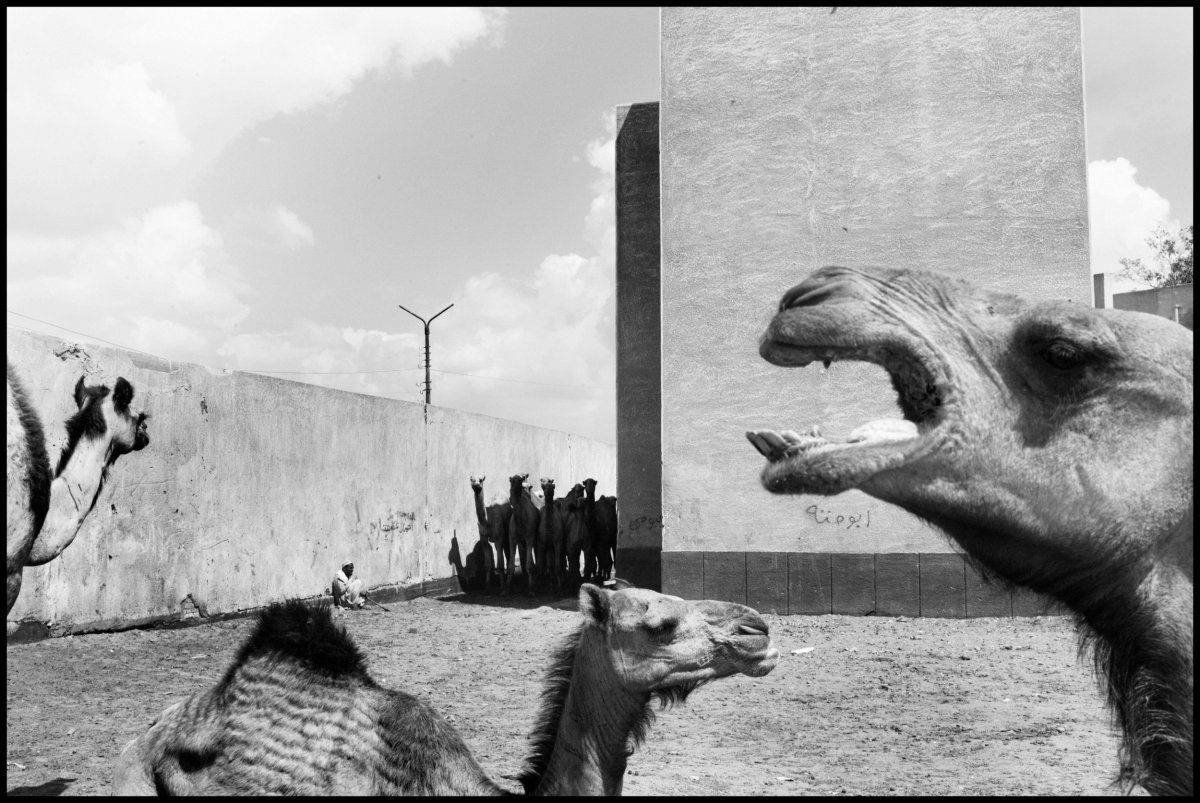

It was those sentiments that inspired Saman's new book, Discordia, published in February, a personal—and artistic—account of his experiences documenting the Arab Spring, from the heady days of protest to the disillusionment and violence that followed. The images are not arranged by chronology or country—Saman's intention was to convey his own experiences of the revolutions overlapping, blurring into one story.

Many of the images in Discordia were taken on assignment for newspapers and magazines. On these assignments, Saman captured the action of the Arab Spring: clashes near Cairo's Intercontinental Hotel and Embassy, a police car on fire, a Syrian rebel fighter taking cover inside a school in Aleppo during fighting. But more of the photos are "outtakes", the less traditionally-newsworthy shots that instead show quieter moments or scenes of daily life that continued amid the turmoil: a pretzel-seller near Tahrir Square; women watching a pro-democracy demonstration in the Tunisian capital; an abandoned hospital in Libya; a boy participating in the traditional slaughter of a cow during Eid celebrations in Cairo.

"A lot of the pictures are very cinematic and look like they could be theater productions and characters," he says, adding that he tried to transcend the journalistic approach of trying to give as much information as possible in one photograph and instead focused more on the ambiguity of certain moments.

Discordia takes that poetic approach further with its interplay between documentary photography and art. The book contains a series of collages depicting the figures of protestors taken from Saman's photographs, in certain poses and gestures that Saman saw repeated throughout the revolutions: throwing rocks, kicking, running away, clashing with the police. The collages were created in close collaboration with Daria Birang, a Dutch-Iranian artist based in Italy, with whom Saman had worked with several times in the past. "I had photographed so many of these situations that we were starting to see a repetition of almost stage-like, performance-like movements," he says. "We wanted to find a way to transmit the energies of these places."

As a personal account of Saman's time in the Middle East, Discordia also deals with some of the dangerous situations he found himself in, including a helicopter crash in northern Iraq in August 2014. "The more time you spend working on a story where the situations are very unpredictable, sooner or later you'll end up in the wrong place or something will happen," he tells Newsweek. "I'm just very lucky that I was able to survive the past five years. Several of my close friends didn't and this book is also a homage to them, in a way." In a short essay at the back of the book, Saman, who is 42, recounts an episode about Anthony Shadid, a New York Times correspondent who died in northern Syria in 2012. One photograph shows traces of shrapnel marking the spot where photographers Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, were killed in Misrata, Syria.

Saman spoke to Newsweek about Discordia and about his experiences in the Middle East over the past five years. The interview below has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Discordia and lots of your other work is much more artistic than traditional conflict photography and photojournalism. Do you identify with the label of "war photographer"—which has often been assigned to you because of the conflict zones you have worked in?

No, I never have identified myself as a war photographer. Certainly I come from a traditional documentary approach to photography. I think everybody has their own voice and maybe mine is not so direct. I tend to take more ambiguous types of pictures that are still quite relevant to the discussion. But ultimately my aim is to try to engage with the viewer, whether it is in a book or a magazine or wherever else.

Did the Arab Spring revolutions feel more dangerous than previous wars that you've covered?

It's hard to say. The danger is always there; it always has been there. But the Arab Spring was more constant and unrelenting. I was based in Cairo so therefore I was covering the region and the region was on fire. That obviously affected the type of stories that I was doing. It was so fast paced that you were basically putting yourself in dangerous situations more and more often, and then it becomes a mathematical equation.

Because you were based in Cairo, you must have felt invested in what was going on. Do you think objectivity matters to your work?

This book is as honest as I can be. Every moment that is photographed is an encounter that I witnessed, but the narrative I create is very personal. This is really not a first draft of history or a lesson on the complexities of the Middle East for the viewer. This is a very personal account that I'm trying to tell with the honesty that I experienced it and in the way that I experienced it.

One theme of the book is the repetition of certain gestures, and the cyclical nature of war and conflict. What does it feel like as a photographer when you've seen it before, that you can almost predict where it is going to lead?

Visually it's challenging, because it's hard to make an interesting picture of something you're so familiar with. I find it harder to get motivated by the same things that motivated me in my early 20s, harder to find something unique or to find really my voice. At the same time, that challenge forces you to think more about what you're doing and to find new ways of telling the story.

Do you think you are less idealistic than when you first started working?

I'm definitely a bit wiser. I am probably less idealistic in the sense that I probably understand a little better the limitations of my role too as a photographer. If now I can contribute to the discussion and challenge a little bit of the black-and-white narrative being given to us, then that's a more important role for me than just giving you the facts or being a more traditional news photographer.

It's about engaging your audience: the sort of photography that asks more questions and makes the viewer react in a more ambiguous way is more engaging. In areas of conflict, there are always narratives of good versus bad and that distinction gets much more complicated. I wanted to tap into that duality of victim and perpetrator, and how those lines blur at the same time.

Have there been any rewarding moments of the past few years covering the Middle East?

On a personal level, yes. Soon after I moved to Cairo, I met my wife-to-be, who was working in Egypt for a think tank. So on a personal level, something really good came out of the Arab Spring. On a professional level, it's been harder to find that positivity, especially after seeing so much death and suffering. Maybe I'm not seeing the full picture yet but I can't say that I saw many positive things, other than great moments of dignity within war. There were great individual encounters and I have met some amazing people, people willing to make the ultimate sacrifice—their lives—for a better situation in their country. That was very humbling to see firsthand.

How does working on a book compare to working on an assignment?

On an assignment, you are encouraged to tell as much information as you can in one picture. The moment you think about building a longer narrative, it becomes more about creating a rhythm and looking for pictures that maybe weren't the peak moment but spoke about other types of situations.

When I started working on this Arab Spring book in 2012, I realized that it made sense to think of things in a more thematic way: to focus on a region and try to support the work that you're doing by taking assignments that have to do with the region that you are interested in. What I was doing before was basically travelling different parts of the world for different stories that didn't really have anything to do with each other if you put them together.

Now that you are based in Barcelona, do you miss being part of the community of journalists that are totally immersed in those situations?

No, not at all. My fiancée and I had both been in the Middle East for quite a long time and we both felt it was time to get some distance. I'm still travelling there quite often. But it's a nice feeling to be able to live somewhere where you don't work. It was also the right time to focus on other things and parts of my life that make up who I am. For my work, it's also quite refreshing. It keeps you with more of a clear mind and you can be more productive that way. It was the opposite when I was in Cairo: the events that were happening there became my life.

What are you working on next?

I'm now working on another longer project on the transnational Kurdish movement. It's sort of related to the aftermath of the Arab Spring in a way, and I'm focusing on the Kurds as a vehicle to tell that story of how the region is changing. That's going to be a couple more years, I think. I'm in no rush to finish it. As you get older, you try to understand a little bit more about what you're doing and to have more control over what you're doing. If you keep going back somewhere, your intimacy with the place and your understanding grows at the same time. Nowadays, I'm not so much interested anymore in single stories that maybe have nothing to do with each other.

In ten years' time, how do you think you will remember the events of the Arab Spring?

The parts that will really stay with me the most are the loss of friends who I will never be able to see again. But looking at the region, it's just so hard to predict. I don't feel it is my role to analyze politics or trends. This is quite a personal experience, and I'm just happy to be able to share it and maybe bring a little more context to a very complex region.

Moises Saman is a documentary photographer and a member of Magnum Photos. The work featured in Discordia has received numerous awards, including the 2015 Guggenheim Grant for Photography, the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund (2014), the Henri Nannen Preis (2014),the World Press Photo (2014), and Pictures of the Year International (2012, 2014, 2015) www.discordiathebook.com

This article originally incorrectly stated that New York Times correspondent Anthony Shadid died in Damascus. He died in northern Syria.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.