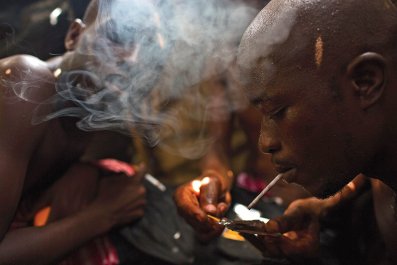

"I've never met a Somali who is not happy when Christians are killed," says Maneno, 29, a teacher at Garissa University College.

Maneno [not his real name] grew up in western Kenya. He studied from borrowed books with no eletric light, bound by the rise and fall of the sun. He dreamed of becoming "a very tough lawyer", but the government, which paid his university fees, compelled him to become a teacher.

Maneno has worked his whole life to "beat the odds". Now, two of his closest friends are dead. He is in shock, jobless, angry and afraid.

And he blames Kenya's ethnic Somali population for his fate.

Al-Shabaab is playing a game of divide and rule, says Mohamed Amiin, a former Somali politician who was in office when the Somali terror group was conceived; delegitimising governance, destabilising society, and driving civilians towards political extremism to increase its own relevance.

Kenya is splitting apart. With every attack by Somalia-based militants al-Shabaab, Kenya's populist government threatens an ever-fiercer response. Its corrupt and heavy-handed security services, funded by the US and the UK, then mete out extrajudicial killings, illegal dragnets, extortion and brutality, primarily among Kenya's Muslim communities.

"We Kenyans have made a mistake," says a Kenyan businessman. "We allowed Somalis into our country, and now they are killing us. Somalis are one, and every Somali is al-Shabaab. Everybody thinks like that."

His grim conclusion, he says, is further substantiated by news that one of the attackers, a Kenyan of Somali origin, was a government official's son.

Somalis have a phrase for Kenyans' ethnocentric attitude: "waryaa ni waryaa", meaning Somali is Somali. It is becoming more prevalent, they say – although right now, it could not be further from the truth. Even supporters of al-Shabaab are turning their backs on the group in the light of their debased attacks. "Massacring students and teachers is not a good political move," says 31-year-old Ahmed Hirsi, a Somali-Kenyan, who once sympathised with the group.

Analysts say the degenerate Garissa attack could signal the group's intention to align with Islamic State. Al-Shabaab rubbished this: "We are a respectable member of al-Qaida," Somali spokesperson Ali Mohamoud Raage tells Newsweek. This is a local war, Raage insists, that could end if Kenya withdraws its troops from Somalia and respects the human rights of Somalis living within its borders.

Boniface Mwangi, a Kenyan activist, is battling to counter the rising tide of resentment against ethnic Somalis, laying the blame squarely at the government's feet. "It's not about al-Shabaab," he intones carefully. "Al-Shabaab are criminals. The blame lies with the Kenyan government that failed to protect its own citizens. It is not about Muslims and Christians."

Kenya, a bulwark against the spread of Islamic terrorism in Africa, has received billions of dollars in foreign funding for its security services. In January, Britain committed a further $87.3 million. But Mwangi says none of this can help if the police remains "the most corrupt institution in Kenya"; nepotistic, unscrupulous, and bent on self-enrichment. Experts fear the West is funding corruption, abuses, generating hatred, and, by extension, furthering the terrorists' cause.

Kenyans fighting to promote unity must contend with al-Shabaab's elegiac prose. Kenya's persecution of Muslims – including "massacres in Wagalla and Garissa in which nearly 10,000 Muslims were summarily executed", as al-Shabaab writes – "has left deep psychological scars".

When Kenya was granted independence in 1963, many of those in the north-east considered themselves Somali. Somalia wanted the territory back. Herdsmen, backed by Somalia, fought Kenya for four years. Kenyans called them shiftas, meaning bandits in Somali. The countries signed a ceasefire in 1967 but ethnic Somalis continued to be targeted and marginalised.

Maneno once got into an argument with a group of Somali-Kenyans in Garissa. They were insisting that al-Shabaab are not Muslims. "That's a lie," Maneno says. "When they were killing our students, they were separating Muslims from non-Muslims."

Maneno adds that a few weeks ago, the KDF, Kenya's army, shot dead four suspected al-Shabaab militants in the Garissa hostel where he was staying. The local community was outraged, claiming the army had killed innocent civilians. "That is why they came to our university," he says.

This time last year, six months after the Westgate shopping centre massacre,

the attacks had not stopped coming. Activists like Mwangi were screaming "the problem is corruption, corruption, corruption"; at the top, money being siphoned off from the security pot, and at the bottom, police whose loyalty could be bought.

Instead of focusing on corruption, the government launched a crackdown on the Somali community. Police went door-to-door, beating, intimidating and extorting bribes. The government said that it arrested over 4,000 people in a week. This prompted an explosion of hate-speech against the Somali community online. Somalis are terrorists, was the message the government gave out.

"They condemned a whole community," says Mwangi.

"If this issue is framed as being between Muslims and Christians, it's going to create a lot of animosity and hatred," he warns.

Maneno calls President Kenyatta's appeals for unity "lipservice"; the government's behaviour makes it clear who is to blame. "This war between Kenyans and Somalis didn't begin yesterday, it began a long time ago," Maneno says, heavy-hearted, on his way to identify two friends' bodies at a Nairobi morgue.

Maneno was a toddler when, in 1984, the Kenya military rounded up thousands of ethnic Somalis and took them to the airstrip of a remote town, Wagalla, 300km north of Garissa. Some were executed, others beaten. Survivors were stripped naked and laid out for days to bake in the sun. Kenya's government claimed 57 died but witnesses said it was up to 5,000.

The nephew of a Kenyan Administration Police officer who clashed with Somalis during this period recounts, with something bordering on pride, his version of the Wagalla massacre.

"They almost wiped out all of them. Somalis wanted to take over North-Eastern [Province]. Like Boko Haram in Nigeria. Most Kenyans think the military are not doing enough."

Dadaab, one of the world's biggest refugee camps that hosts 336,000 Somalis in Garissa County– "should be wiped out. The Kenyan public thinks that even Eastleigh should be wiped out."(After Garissa, police ramped up their night-time raids in Nairobi's Somali quarter, Eastleigh.)

Only the government can dismantle this violent, sectarian vortex before it becomes civil unrest, and it is feared that their time is running out.