Warning: Article contains graphic images

A dolphin in Australia choked to death on a giant octopus after trying to swallow the creature whole.

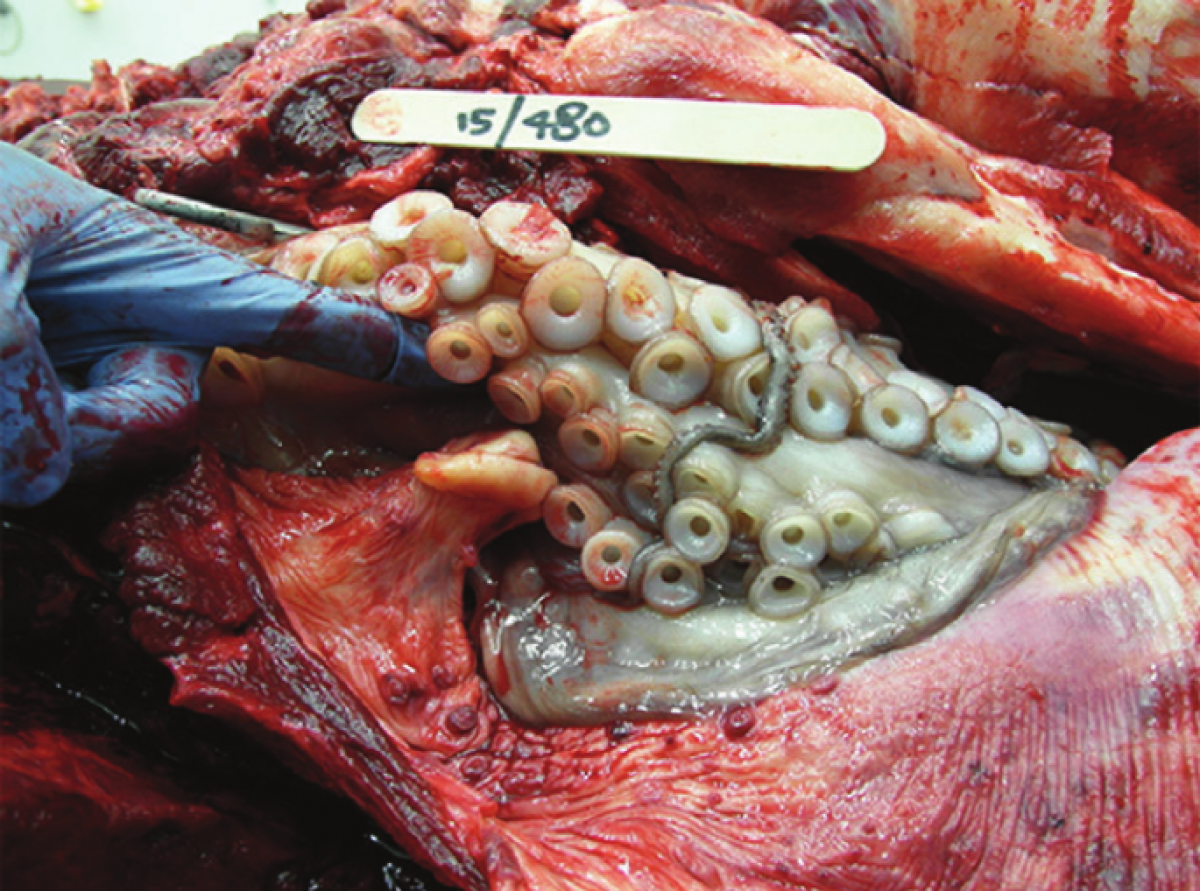

The bottlenose dolphin was discovered on Stratham Beach, Western Australia on August 30, 2015, with an octopus sticking out of its mouth. Scientists took the carcass away for analysis, and soon discovered it was an adult male named Gilligan that they had been tracking since 2007.The dolphin had never been observed feeding on giant octopus before.

Researchers from Murdoch University, Australia, took the dolphin away from an autopsy. Their results were in the journal Marine Mammal Science on Monday.

Scientists know bottlenose dolphins occasionally feed on octopus. Researchers at Murdoch have previously observed that they shake the octopus at the surface of the water and throw it up into the air to remove its head. This also helps to tenderize the arms and break the octopus into little pieces so the dolphin can eat it more easily.

In the study, researchers note that while some of the octopus was protruding from Gilligan's mouth, most of it was stuck in its throat, obstructing its pharynx, larynx and oesophagus. One of the octopus arms reached all the way down to the dolphin's first gastric compartment.

After removing it, they found the octopus weighed 2.1 kilograms (4.6 pounds) and had an arm span of 130 centimeters (51 inches). The dolphin was 242 centimeters (95 inches) long.

"The findings were consistent with the cause of death being due to non-drowning asphyxiation, specifically suffocation, caused by choking," the authors write.

"Given octopus arms and suckers remain active and functional for over an hour, they would far outlast the breath-holding capacity of any dolphin...The dolphin would have been no match for the octopus' tenacity, and it is unknown how long this individual might have struggled to free its larynx from choking before succumbing."

They refer to another similar case recorded in 2009 when another bottlenose dolphin had choked to death on an octopus 162 kilometers (100 miles) from where the latest case was found. No autopsy was carried out on this carcass, however.

Octopus arms and suckers remain functioning after death and dolphins have to disengage their larynx to swallow them, posing a risk to the dolphin. As a result, the authors say there must be some reason why dolphins would engage in this potentially dangerous behaviour.

"It likely comes down to risk versus reward—large muscular cephalopods [the class which includes octopus , squid] are an excellent, concentrated source of high quality proteins, and most cephalopods tire rapidly following a period of fast swimming." This, they say, makes octopus slow and sluggish, lowering the risk of it choking the dolphin.

The team says that because dolphin energy consumption is so high, they have to balance the fuel benefit of an octopus against the risk involved. "Assuming an octopus is sufficiently processed to render its arms into small enough fragments such that they and their suckers can be effectively and safely swallowed, their consumption must generally be a risk worth taking, although it did not play out well in this individual's case."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.