It's a moment that will undoubtedly haunt him as long as he lives: Don Cheadle, dressed as a car wash attendant, backup dancing in a 1989 music video for R&B star Angela Winbush's hit song "It's the Real Thing." Cheadle, then a struggling actor, had shown up for a friend's casting call and was recruited by the choreographer Debbie Allen. The result, an '80s extravaganza of cheese—big hair, shoulder pads, bedazzled hats and synthesized beats—would look right at home in Cheadle's new Showtime comedy, Black Monday (premiering January 20).

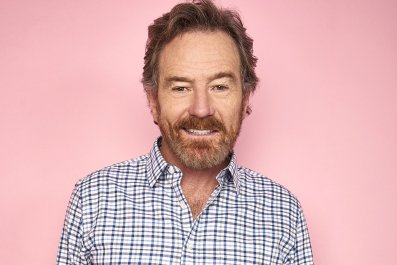

The series takes place during what is often called the Decade of Greed, an era of conspicuous consumption fostered by the Reagan administration—inspiration for not only Oliver Stone's biting critique of financial predation, 1987's Wall Street, but also the current U.S. president, whose identity was forged in the gilded excess of the '80s. Cheadle plays a manic stock trader named Maurice "Mo" Monroe. The actor has a curious nostalgia for "the clothes, the shoes and the terrible synth music that came out of that time," but his fondness ends there. "I graduated from CalArts in '86," he tells Newsweek. "It was a very demonstrable period: Show out, show off, be loud, be bold. Do all the drugs. Have all the sex. There wasn't a lot of introspection."

Cheadle has no particular fondness for films or shows about people with money either. "Actually, a lot of times it disgusts me," says the actor, a noted activist involved in human rights and climate change issues. (Cheadle has co-authored two books, including Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond.) "That kind of gluttony is hard to take."

And yet, just two years after the 54-year-old wrapped five seasons of Showtime's House of Lies—where he earned a Golden Globe playing a ruthless management consultant named Marty—he's back in the world of money, money, money. "In both cases, I blame David Nevins," says Cheadle, referring to the CEO of Showtime. What makes his new dark comedy "palatable and enjoyable," says the actor, is that it is also a scathing takedown of excess. Black Monday flirts with satire, the tone as frenzied and irreverent as the title character, who, among other things, does coke with his robot butler and karate-chops doors down. "I hope people want to watch us, because it's not like anything I've ever seen on TV before. [My character] is wild in the best way—made of gamble, insanely unafraid, with no anchor and no balance."

The story, from creators David Caspe (Happy Endings) and Jordan Cahan (My Best Friend's Girl), fictionalizes an explanation for the stock market crash on Monday, October 19, 1987. (The opening credits of the pilot, directed by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, claim, "No one knows what caused the crash…until now.") Mo's goal is to take his No. 11 team to No. 1 on Wall Street—if only he had the cunning of Marty on House of Lies. "Mo's not nearly as intelligent," says Cheadle, an executive producer of the show.

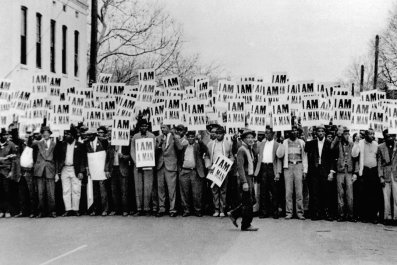

Perhaps not so true to life is that Mo's ragtag team of Wall Street traders is remarkably diverse for the time. There was no pushback on such reality-bending, says Cheadle. "That was the point of what we were trying to do. These characters get to do things that you wouldn't get to if we were a traditional 'house' of 98 percent white men. We already know how it would be if it was Leo DiCaprio and Jonah Hill. How do these guys do it?"

Regina Hall (Girls Trip) plays fierce trader Dawn; Andrew Rannells is the firm's only straight white dude, a fresh-faced newbie named Blair; Horatio Sanz, as Wayne, is Latino; Yassir Lester, as Yassir, is Muslim. It was Cheadle who pushed to cast Hall, who recently became the first black woman to win a best actress award from the New York Film Critics Circle, for 2018's Support the Girls. He had seen her pull an audacious stunt at the 2016 American Black Film Festival Honors. "Regina King was being honored," says Hall. "She and I get confused all the time—her picture gets put in for mine and vice versa. So we played a joke. We didn't tell the stage people, but when they announced 'Regina King,' I walked out giving kisses, waving, got to the podium and said, 'Thank you so much, everyone!'"

Cheadle was impressed. "Her humor and her humanity—it all came through in that three minutes that I saw her onstage. I thought, That's Dawn! A lot of other names and different ethnicities came up, but I said, 'If Regina says yes, just give it to her.'"

Hall loves that Dawn is "a woman whose function is not in connection to the male character—meaning that she isn't the wife, and it doesn't feel auxiliary. She plays the same game men play." Dawn is a married woman who, nonetheless, exploits the underlying romantic tension with Mo; by the third episode, she has tricked him into making her a partner at the firm.

As it turns out, there was a black female trader in the '80s—a surprise to Hall, who tracked her down. "We talked about how forceful she had to be just to be heard," the actress says.

Cheadle turned to the 1991 book Den of Thieves, James B. Stewart's best-selling account of the insider trading scandals of the mid-'80s. Though the junk bond deals of financiers like Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken were illegal, the laws were rarely enforced until 1989, when Boesky and Milken were convicted of fraud. "One of the most interesting things Stewart shows," says Cheadle, "is how people were willing to work around every rule and regulation because the reward is so potentially—well, rewarding."

The biggest challenge was playing high. "Mo's done a lot of coke," says Cheadle. "Your body doesn't know that you're just acting when you've been doing that for 14 hours. You leave the set, and you're like, 'Wow, why do I feel so edgy and nervous?' That can be hard to drop."

Did he, as actors often do, have to find a way to empathize with Mo? "No," he says flatly. "People like that are making moves for themselves and shitting on everyone else. I don't have a lot of empathy for him, and I tend to cheer when he gets his comeuppance."

The series is obviously critical of both the decade and Wall Street, but it's not, says Cheadle, a comment on current corruption. Nor is it "trying to make some statement on race," he adds. "It's not medicine in any way, shape or form." Rather, it's a new story that "you wouldn't get to with 98 percent white men. We are the wretched refuse of the upper crust of blue-blood, elite white boys."