Updated | This is a weird theory, but bear with me: Donald J. Trump is Andy Kaufman wearing a disguise.

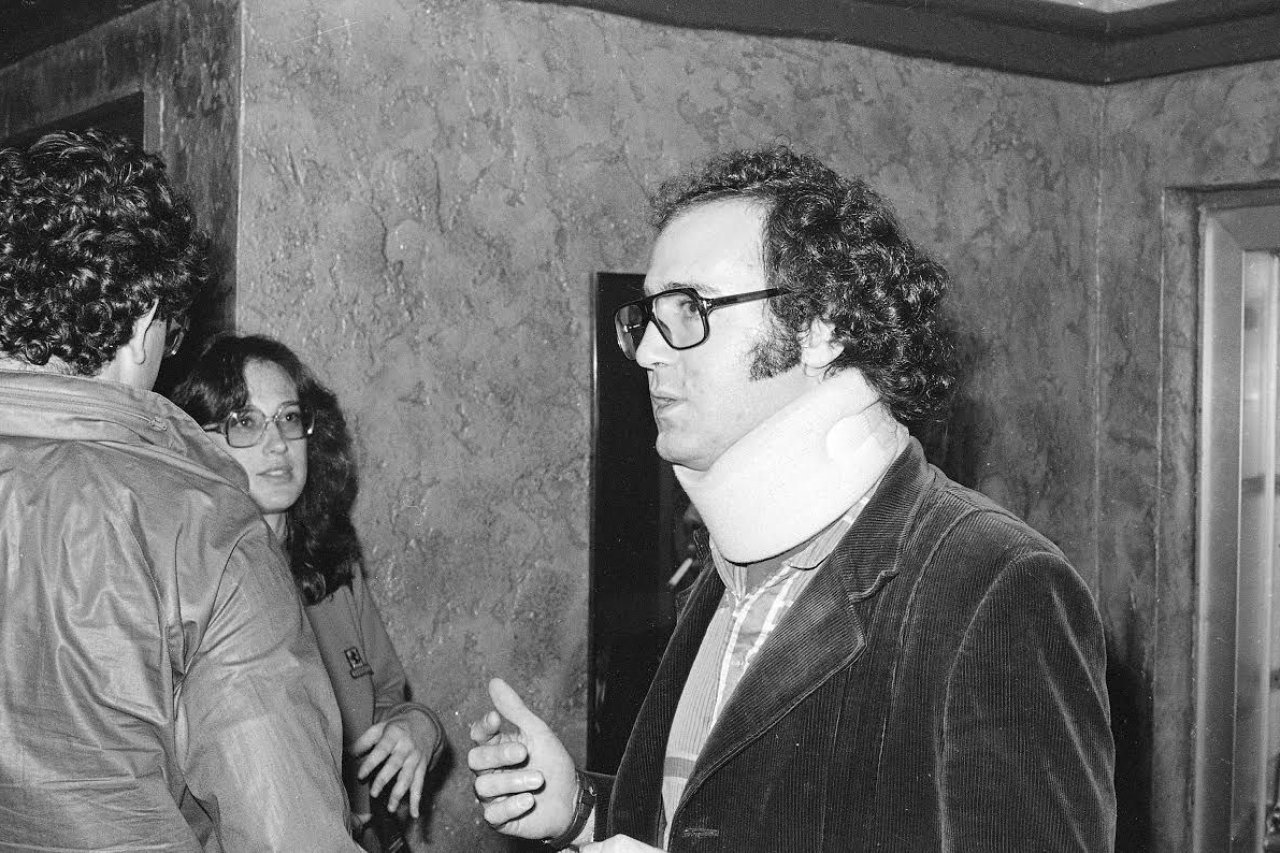

Forget the logistical obstacles. Ignore the temporal and practical impossibilities: that Andy Kaufman died of lung cancer in 1984, that Trump has a life story far predating Kaufman's career, that the two men bear little physical resemblance, that Trump's wives and children haven't let slip a word about the ruse. Just consider that the GOP presidential nominee is a character invented and, with characteristically unflinching dedication, performed by the performance artist Andy Kaufman. It's simple. Einhorn is Finkle. Finkle is Einhorn. Trump is Kaufman.

The theory is nuts. So is the fact that it has exploded into a de facto refrain during the 15 months the orange-haired mogul has spent as a presidential candidate. It is a conspiracy theory. It is a rationalization. It is a defense mechanism. Trump says something appalling? "Ha-ha! Andy Kaufman sure is getting us good," you reassure yourself. Trump's about to appear onstage at the Republican National Convention? "Andy will finally take the Trump mask off now," you mumble to your cat. Trump wins the election and moves into the White House? You squirm. "How far is this gag gonna go?"

Though the idea predates the present election—comedian John Mulaney tweeted that Trump is Kaufman in 2012 but doesn't remember what sparked it—it has achieved remarkable prominence in 2016. There are memes and Photoshopped images depicting the late Kaufman grinning as he holds up a mask of Trump's face. (He seems to be saying, "Gotcha!") There is a satirical news story, published on the website Stubhill News, imagining Trump announcing that he was "actually Andy Kaufman the whole time." And during the summer, as the Republican National Convention unleashed a new season of Trump Theorization Syndrome, Don Cheadle changed his Twitter avatar to an illustration of Kaufman stepping out of a full Trump bodysuit.

Oh wow.. @DonCheadle's avi is Andy Kaufman stepping out of the Trump suit. Genius. Entirely possible. @GregGoodfried pic.twitter.com/P00bJSlhAL

— Justin Kanew (@Kanew) July 31, 2016

The Kaufman theory hinges on the notion that Trump's bid for the presidency is so outlandish—the gaffes, the boasts about penis size, the policy reversals and white nationalist overtures—that it must surely be performance art. More specifically, the work of Andy Kaufman, an idiosyncratic figure who yanked performance art in bizarre, unprecedented directions, whether he was impersonating an incompetent comedian known as Foreign Man or pretending to revive an elderly lady who feigned a heart attack on his stage.

The theory is weirdly cemented in election rhetoric. Even weirder, different iterations of the joke often seem to have sprung up independently of one another. Every single day, somebody somewhere tweets that Trump is Kaufman.

I can't wait for this "Trump" character to remove his mask, revealing Andy Kaufman.

— Eli Attie (@EliAttie) August 2, 2016

Maybe the October surprise will be that Donald Trump actually died years ago and this has been Andy Kaufman all along.

— Joe Gandelman (@JoeGandelman) September 18, 2016

Am I the only one starting to think we might eventually discover Trump is just some elaborate Andy Kaufman character?

— Jim Gaffigan (@JimGaffigan) August 4, 2016

Still waiting for Andy Kaufman to pull off Trump mask & say: "What’s real? What’s not? I test how other people deal with reality in my act”.

— Bryan William Jones (@BWJones) August 2, 2016

…and that we'll learn the truth on Election Day:

November 9th, 2016. The day we find out Andy Kaufman is alive and behind the Trump campaign.

— â˜ï¸ Business Of Dreams â˜ï¸ (@BusinessOfDrms) July 25, 2016

…or maybe on Halloween:

On Oct. 31 Andy Kaufman will prove he's alive by pulling off his Donald Trump mask. Only reasonable explanation.

— Adam Bednar (@Bmorejourno) August 3, 2016

Adherents of the Trump-Kaufman Hypothesis vary in their seriousness (and looniness). Erik Vance, a 40-year-old science writer based in Mexico City, was among the first to champion the Kaufman connection. He articulated the theory in detail months before Trump declared his candidacy. It was September 2014. Vance was disturbed by Trump's "ignorant babble" about the dangers of vaccines. "I remember thinking, 'This guy has got to be pulling our legs,'" Vance says. "I'd seen Man on the Moon a while before. I just started thinking about other people who mess with us." His brain landed on Andy Kaufman; Trump's demeanor suddenly reminded him of Kaufman's more abrasive characters. So he took a Trumpian leap of logic. "What evidence is there that they're not the same person?

"All you gotta do is watch one Tony Clifton video and you realize, this is Trump!" Vance raves. "He's saying these audacious horrible things that he's not serious about, but he doesn't care! It's just one big joke for him. And it's brilliant. You watch Donald Trump and you can't help but think, 'No one can think this stuff!' I imagine Trump going home at night and putting on a beret and listening to Rachmaninoff and discussing postmodern theory."

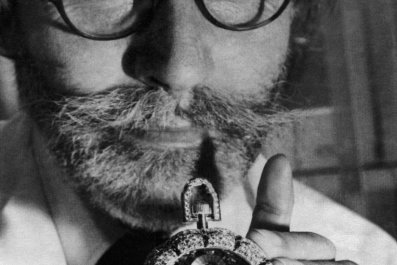

It's a crucial distinction: Kaufman fans frequently aren't comparing Trump to Kaufman so much as they're likening him to Tony Clifton, the belligerent lounge-singer character created by Kaufman in the late 1970s. As Clifton, Kaufman would don a filthy mustache and shout insults at audience members in a voice that resembled a coked-up Bugs Bunny's. Kaufman frequently insisted on having Clifton perform as his opening act, confusing both audience members and media outlets who didn't realize it was just Kaufman in a wig.

Within days, Vance popped out a blog post titled "Donald Trump Is the World's Greatest Performance Artist." The piece outlines the theory in remarkable detail:

I believe that Kaufman created his Donald Trump character sometime around 1972, as a precursor to his equally jarring Vegas lounge singer, Tony Clifton. As the comedian gained fame and money, he worked doggedly to build a backstory for Trump, making him the son of a New York real estate agent, a graduate of the Wharton School, and giving him a stint in military school.

As both Kaufman and his Trump character became more successful, the comedian had to increasingly rely on his brother Michael and collaborator Bob Zmuda to take turns playing Trump. In 1983, exhausted and frustrated that he couldn't dedicate more time to the Trump project, he made a decision. He would fake his death, undergo reconstructive surgery, bleach his hair into an elaborate comb-over, and become Trump full time.

A year and a half later—shortly before Trump sealed up the Republican nomination—a retired Brigham Young professor named Eric Samuelsen wrote his own blog post musing that Trump is really Kaufman.

"What makes it plausible is the sort of huge pranks that Kaufman loved," says Samuelsen, 60, a longtime Kaufman fan. "He loved pulling stuff like that. He made up his entire feud with Jerry Lawler." Trump's campaign, Samuelsen observes in his essay, "is precisely similar to Kaufman's comedy." The overarching idea is the same as Vance's, though more overtly tongue in cheek. And Samuelsen speculates that someone had the real Trump killed, while Vance suggests that there was no real Trump—this was a character created by Kaufman all along.

What about Trump's children? His wife? "He's clearly paid actors to play his family and friends," Vance tells me. "And while his persona might be fake, his money is real. So he's been able to create a fiction of himself." The mystery is whether he'll ever reveal his gag. Kaufman really did concoct abusive, brash characters, like Clifton. "Andy wouldn't come out afterwards and say, 'Thanks, folks, it was all a joke.' He would just walk offstage."

Does Vance really believe any of this? When I ask him, he becomes flustered. He answers in fits and starts. He's a journalist. He knows it's ludicrous. But part of him won't let go—especially now that the election has proved some of his observations prescient. "The world would make more sense if this whole thing was a joke," he insists. "And I would laugh along with it. As long as it didn't end up with a crazy person in the White House."

***

Trump-Kaufman truthers are kidding—mostly. But as with other ostensibly crackpot theories—aliens built Stonehenge, or the CIA masterminded the Kennedy assassination—this one persists because it has the capacity to explain so much about so much that cannot be explained. These theories catch on because they contain some trace of an elusive truth. It's the pseudo-intellectual's version of "I can't believe this isn't The Onion."

Among the pundit class, Trump's unhinged campaign has sprouted dozens of unlikely theories: that he is deliberately trying (and failing) to sabotage his own campaign, that he might win the election but refuse to take office, that he is only really after revenge, that he is only really after TV ratings, that he might choose his daughter Ivanka as his vice presidential pick, that his whole campaign is just a wild scheme to launch Trump TV. (Hillary Clinton has been subject to outlandish theories of her own, like the recent right-wing charges that she's gravely ill or being played by a body double.)

If these notions are within the realm of plausibility, why not Kaufman? The elemental insight here is that Trump's campaign works as exquisite satire, whether he intends it or not. The man has successfully exposed pundits as pompous charlatans laughably removed from the average voter. He has wreaked havoc on the news media's obsession with false equivalence. He has stripped bare the bigotry undergirding the immigration debate. And, most of all, he's spotlighted the moral bankruptcy of the GOP itself—hence the spectacle of Paul Ryan denouncing Trump's attack on a federal judge as the "textbook definition" of racism while declining to withdraw his endorsement. "It's a very bizarre election season," says Vance, "and it feels almost scripted by some sort of comic genius."

So the Kaufman conspiracy succeeds by patching together two theories that already have widespread traction: (A) that Kaufman faked his own death and (B) that Trump's campaign is a gag with a punchline. Theory B has been championed by Last Week Tonight host John Oliver, who recently implored Trump to drop out and reveal that his candidacy was a satirical stunt all along. This is the one way for Trump, faced with the prospect of a humiliating defeat by Clinton, to redeem himself: "If you drop out in order to teach America a lesson, you would not be a loser," Oliver urged. "You would be a legend."

Meanwhile, rumors that Kaufman's death was some grand hoax have persisted in the three decades since he "died." Kaufman deserves some blame: When he was alive, he spoke of wanting to fake death as the ultimate gag. Then he succumbed to a rare cancer—so we think. "He was a consistent practical joker," says Kaufman college buddy Al Parinello. "If there's any human being on the face of this earth who might be able to pull it off, it would be Andy." We see this in Man on the Moon, Miloš Forman's 1999 biopic, when Kaufman (Jim Carrey) reveals he has cancer and his agent thinks he's pulling a prank. Parinello says he's 90 percent convinced his friend's death really was a hoax. "I know that sounds crazy," he says, but "if you were living my life, you'd understand it."

But you don't need to be living Parinello's life to understand that Kaufman was fascinated with the blurred line between life and death. Much of the theorizing around his demise involves a guy named Alan Abel, a legendary prankster who in 1979 really did fake his own death in an astoundingly well-organized con. Abel tricked The New York Times into running his obituary, then gleefully hosted a press conference to gloat that he was very much not dead. Kaufman then befriended Abel and took obsessive interest in this hoax. When the two met for dinner in New York, "he wanted to know every detail," says Abel, who is 92 and still not dead. "I told Andy exactly what I did, and he was taking notes. He continued his interrogation and I gave it to him again, step by step. I had to have a wake. I had to have musicians ready to play there, and I had to have a caterer. I had to have a couple of people who were going to speak."

There was a flurry of renewed speculation regarding Kaufman's death in 2013, when Kaufman's close associate Bob Zmuda and ex-girlfriend Lynne Margulies published a strange book claiming that Kaufman really had faked his death and would soon reveal the 30-year hoax. No such luck.

The "evidence" often contradicts itself. Kaufman's brother once claimed to have received a letter from Andy more than a decade after his death but now seems to disavow the hoax myth. "People who went to his funeral pinched him to make sure he was dead," Abel says. But Parinello was at the funeral and claims Kaufman was a high-level meditation expert. With meditation, he insists, "you can actually control certain physical responses of the human body. You can slow your heart rate down to a point where you might actually be diagnosed as a person who is no longer living."

Abel now strongly doubts Kaufman is alive. "I would say it's 90–10 against him coming back. The 10 percent? I leave the door open for that possibility."

After Abel executed his own stunt, some of his friends were furious. He has college classmates who still refuse to speak to him. "They grieved for a few days and now, suddenly, uh-uh. To them, it's a dirty trick. You don't fool around with death." But if Kaufman does return, Abel promises he won't be mad.

"I'd be the first to hire a band and hold a party and celebrate," he says excitedly. "I'd welcome him home. He'd probably be the same Andy that he always was." Abel's 92, so Kaufman better hurry the hell up.

***

Is Trump really Andy Kaufman?

I contacted CMG Worldwide, Kaufman's "exclusive licensing agent." The business agent says it's dedicated to "maintaining and developing a positive brand image" for Kaufman—a curious thing, considering the comedian has ostensibly been dead for 32 years and, when alive, delighted in nothing more than lambasting the very notion of a "positive brand image."

I reached Chairman and CEO Mark Roesler, who had little patience for my query about the possibility that his long-deceased client might be reincarnated in the form of a billionaire demagogue. "Congrats," Roesler emailed back. "Sounds like you are really on to something. Why don't you talk to Andy." Maybe Roesler knows something I don't? I asked if he could forward my message to Kaufman. I never heard back.

I started contacting Kaufman's old friends and associates, expecting equally dismissive replies. Instead, those who knew the comedian seemed intrigued and even delighted by this crackpot theory.

"If he were Donald Trump, that would be the best gag ever in the history of gags," says producer Bob Pagani, who was friendly with Kaufman during the last few years of his life. The gag would fit with the comedian's abrasive provocations. "He always said that what he was interested in was an honest reaction. If it was anger, if it was laughter, whatever. He always said, 'If you laugh, I want you to laugh in the gut.'"

The comedian Elayne Boosler says she has seen the Trump-Kaufman joke all over. (Boosler dated Kaufman for several years, lived with him in the Village and later credited him with inspiring her own career.) "I think it's a great tribute to Andy that a character such as Trump is credited to him," Boosler wrote in an email. "Like Andy's creations, Trump boggles the mind in such a way that leaves people saying, 'This can't be for real.' In a performance artist, that is genius. In a presidential candidate, it's unimaginable."

Though he took glee in toying with his audience's emotions, Boosler noted, Kaufman made sure fans were safe and let them in on the joke eventually. There was an intensity and a mischievousness about him, but also a sweetness. "I think people want Trump to be Andy, just to feel that now." What Boosler is saying, I think, is that Kaufman would not burn the world down for the sake of a gag. Others aren't sure. "Andy just never gave up," says Abel. "He always went forward. Just damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead." As for the Trump theory, "I think it's a hilarious possibility. And it makes a lot of sense. Every time Donald opens his mouth, it's Andy Kaufman."

The comedian's younger brother, Michael Kaufman, is flattered by the phenomenon. He boasts that his brother's name "has been mentioned more than any other nonpolitical figure in this election."

The younger Kaufman refused to address the death hoax rumors. He isn't happy about that book Zmuda and Margulies put out. But "I think it's great the attention that Andy is getting," he says. "It should be a compliment to [Trump] that he's being compared to Andy." What would Andy think of it? "I think he would be saying, 'Wow, I've been dead for 32 years and people are still talking about me.' If you can have an ego from your grave or wherever you go after that, his would be fed quite well right now."

Kaufman was uninterested in politics, his brother says. (Al Parinello seconds this view: "Totally apolitical. Nothing. Nobody. What he supported was tall women.") But had he met a young Trump 35 years ago, "he probably would have added that to his cast of characters. Tony Clifton, the wrestler and Trump. They're similar to each other." (There is no known evidence that Kaufman ever did meet Trump, or that the two men were seen in the same place at the same time.)

My favorite conspiracy theory: Donald Trump is really Andy Kaufman playing Tony Clifton playing Donald Trump. pic.twitter.com/TTHTIJDonK

— Bryan Lunduke (@BryanLunduke) March 15, 2016

For disciples of Kaufman's Clifton character, the Republican nominee's mannerisms are familiar. "When Trump walked onstage at the GOP convention, he looked like Tony Clifton to me," says Kaufman's brother, who has also played the Clifton character. "There was something about his walk and his stature, demeanor. Before he ever said a word, just walking to the stand to speak, I said, 'Wow. Tony Clifton.'… It's the personality that the wrestler has and Tony Clifton has—Trump reminds people of that, I think."

Fans have spotted other parallels between Clifton and Trump. "Their attitudes towards women are probably along the same lines," says Vance, the science writer. Plus, there's the swagger, the aggravated New Yorky accent.

"He's got the pucker—the lips," Vance adds. "He puckers up. I can't believe someone hasn't gotten rid of that with Donald. He's got that pucker that's exactly like Tony Clifton. Tony Clifton's got terrible hair. But I think Donald's got him beat on that. Just the brashness and the doubling down. If you ever watch Kaufman being Clifton, he doubles down. He'll say something and then anger people [and] he'll just double down. It's really funny when he's onstage." Vance considers the present situation. "I guess it's less funny now."

Kaufman's old friend Parinello is now an impassioned Trump supporter. Though he insists Kaufman had several un-Trumpian qualities ("There wasn't a moment in Andy's life when he cared about money—it just was totally irrelevant to him"), he sees lots of commonality. "Andy Kaufman and Donald Trump are two of the boldest human beings to ever exist on this world," he insists. "That is no Hillary Clinton." Of course, Clinton's pitch to voters is rooted in her competence and stability—not exactly Kaufman-like qualities. She could probably run on the slogan "I Am Definitely Not Andy Kaufman" and soundly win.

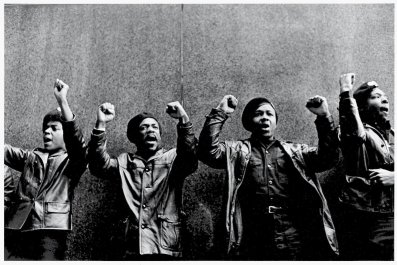

Others compare Trump to Kaufman's embattled wrestler character, who would challenge women onstage and offer them $1,000 to beat him. "On the campaign trail, Donald has been playing a very specific role from professional wrestling called the heel," observes Michael Jennings, a Kaufman fan who never met the man. The heel is basically the villain. "And Andy loved being the heel. He loved feeding off all that violent, hateful energy.… I sincerely believe he would have adored Trump's performance throughout this election cycle."

This wording is curious: It's not politics. It's performance. Trump ought not win the White House so much as he should win an Emmy. Like Kaufman, he has vastly more experience in the entertainment sphere than in politics. In future decades, theorists will perhaps single out his nomination as the first postmodern bid for the presidency: He is not so much running for president as he is performing and contorting what it means to be a presidential candidate. (For best effect, read this line in a Slavoj Žižek voice.)

But the Kaufman conspiracy is all fantasy. Trump is real. He has the boyhood photos to prove it. His father, Fred Trump, was building supermarkets pre–World War II. "It's preposterous that people would actually think it's true," Michael Kaufman insists. And what's also real is that Trump—or Kaufman as Trump, or Tony Clifton or whomever—could very well take the oath of office on January 20, and his xenophobic proclamations won't be conceptual art. They will be state-sanctioned policy.

The sheer joy of an Andy Kaufman performance is that you have no idea what might happen. The sheer horror of a Trump presidency, for the overwhelming swath of the country that loathes him, is that you have no idea what might happen. So saying he's just Kaufman is a goofy reassurance. It's a way to ascribe meaning to a world without meaning, a world as chaotic and unpredictable as the grammatical decisions in a Trump tweet.

"If this whole thing were a joke, I think there would be a lot of nervous but relieved laughter across the world," Vance says. He chuckles. "We should be so lucky."

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly gave the pseudonym Bob Arctor of an Andy Kaufman fan. His real name is Michael Jennings.