They've come for William Shakespeare. They are the purveyors of outrage culture, which seems increasingly to shape tastes (and distastes) of modern-day America. But they are not, as one might expect given recent incidents, liberal "snowflakes" bemoaning cultural appropriation or complaining about insufficient trigger warnings. Instead, the outraged in this instance are members of the political right who say that a production of Julius Caesar in New York City is being staged in a manner that endorses the assassination of President Trump.

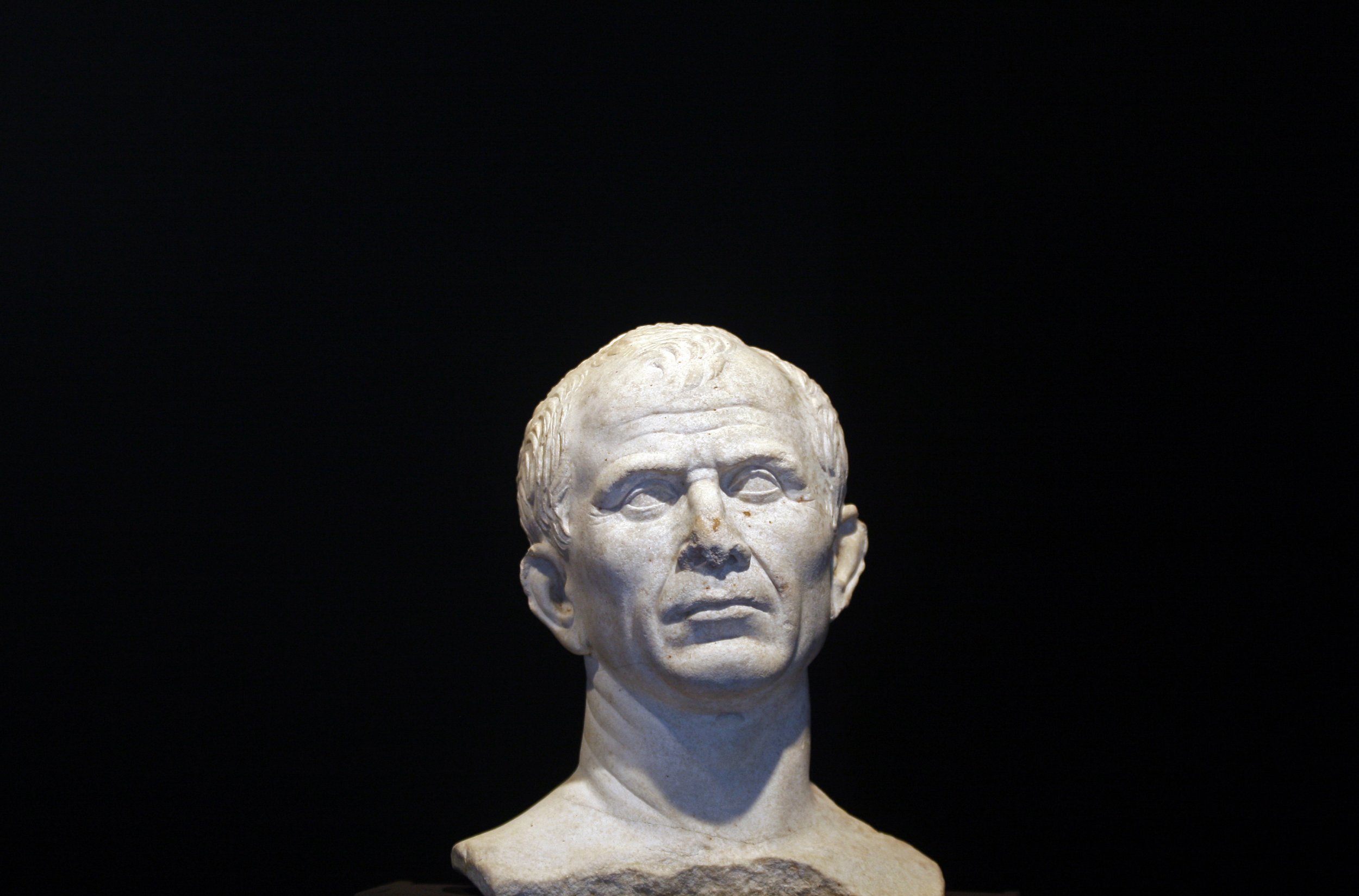

Shakespeare set Julius Caesar in ancient Rome but in the modernized version staged by the Public Theater as the centerpiece of Shakespeare in the Park, the Roman leader is played by actor Gregg Henry in a way reminiscent of Trump: red power tie several inches too long, sandy hair combed-over. That obviously intentional resemblance has troubled some, since Julius Caesar is assassinated in the play. Dying, he utters one of Shakespeare's most famous lines: "Et tu, Brute? Then fall, Caesar!"

Read more: Delta Airlines and Bank of America withdraw sponsorship from "offensive" play

Shakespeare in the Park is famously free (unless you count the preposterously long lines), but that makes corporate sponsorship necessary. In response to the outrage from the political right, however, both Bank of America and Delta Airlines have withdrawn their support of the event.

The rising anger over the Shakespeare in the Park staging of Julius Caesar was in part stoked by Donald Trump, Jr., who has lately been mounting a largely counterproductive defense of his father. But furor had been gathering in the right-wing media ecosystem over the past week, according to a report in The New York Times:

Last week, the website Breitbart compared the play to the controversial online photo that showed the comedian Kathy Griffin holding a severed head that resembled the president.

Criticism of the play reached a fever pitch on Sunday when Fox News reported that it "appears to depict President Trump being brutally stabbed to death by women and minorities."

Corporate sponsors fled like Gauls from an advancing Caesar. Delta said the production "crossed the line on the standards of good taste," while Bank of America said that certain choices of direction and dramaturgy "intended to provoke and offend." For his part, director Oskar Eustis has defended his production, pointing to Julius Caesar in a letter on the Public Theater's website as a timeless statement against tyranny and "a warning parable to those who try to fight for democracy by undemocratic means."

I wonder how much of this "art" is funded by taxpayers? Serious question, when does "art" become political speech & does that change things? https://t.co/JfOmLLBJCn

— Donald Trump Jr. (@DonaldJTrumpJr) June 11, 2017

The critics of the Public Theater have a point here, though it's not quite the one they wanted to make. The true offense Eustis causes is not to Trump, but to Shakespeare. As Eustis notes in his letter to the audience, the Bard's work has the uncanny ability "to seem fresh, and new, whenever we encounter it again." If that's true, why slather Julius Caesar in such obvious contemporary symbols? Why make a play about Caesar a play about Trump?

The staging choices that seem to have enraged the right (I haven't seen the play; nor have most of its critics) are all unnecessary. Costume designer Paul Tazewell, who worked on the hit musical Hamilton, clearly has the talent and imagination necessary to transcend the toga-party aesthetic of a traditional Julius Caesar production. But he should also have seen the trap of rendering the play in such relentlessly timely fashion.

Anyone who seriously engages with Shakespeare's language will invariably turn to a reflection of the political situation, without the overt prodding of a Trump lookalike. Animus for Trump already overflows in liberal enclaves like New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles. While theater need not be a respite from reality, it should lead with art, not the evening news. Eustis is an enormously accomplished director, but now the entire effort has been subsumed by a pointless political fight.

At the same time, I am not going to take theater criticism from Donald Trump, Jr., — and neither should anyone else, regardless of his or her political beliefs. Only someone who has never read Julius Caesar can possibly think the play a celebration of political violence. Although Shakespeare may have been responding to the political tumult in Renaissance England, and making comment on absolute monarchy, his genius lay in transcendence of the specific. Julius Caesar is not the hero Julius Caesar, but neither are the conspirators who bring him down (principally, Brutus and Cassius), or the friend who comes to his defense in a rousing funeral oration (Mark Antony).

When I taught to the play to my 9th graders in Brooklyn at the beginning of the school year, it was always with a focus on the ordinary people of Rome, who seem to be so easily swayed by one powerful personality, then another.

"Worse than senseless things" they are, says the tribune Marullus in the play's first scene, these "cruel men of Rome" so fickle in their desires. As far as the crimes of Julius Caesar are concerned, murder is subservient to exploitation, and the ease with which the masses are compelled to rabid action by a persuasive speaker. That's best demonstrated by Marlon Brando playing Mark Antony in a 1953 production of Julius Caesar. I always showed that in class, and my students always loved it, Brando rousing the crowd with Mark Antony's devastatingly sarcastic words:

When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept:

Ambition should be made of sterner stuff:

Yet Brutus says he was ambitious;

And Brutus is an honourable man.

Shakespeare's public swings from one conviction to another, from praise to outrage and back again. And they don't even have Twitter to stoke the civic fires.

Shakespeare may not have had a better interpreter in the 20th century than the poet W.H. Auden, who in 1946 delivered a series of lectures on Shakespeare at the New School for Social Research in lower Manhattan, just a few subway stops away from where Shakespeare in the Park is being performed today. In his discussion of Julius Caesar, he notes that during the 1930s, there was a tendency to stage the play as a comment on the rise of European fascism.

"That's a misreading," Auden told his students. The play is not about great men, but the great mass of men. Auden surmised that Rome was "doomed not by the evil passions of selfish individuals, because such passions always exist, but by an intellectual and spiritual failure of nerve that made the society incapable of coping with its situation."

"Julius Caesar has great relevance to our time," Auden told his students, warning that Western society was "in immense danger."

I suspect that the controversy over Julius Caesar now taking place will end up being more captivating than the Public's Julius Caesar. For while the outrage is ugly, it may end up saying more about who we are, and the way we are, than what appears to be a needlessly political staging of the play.

And what this latest outrage does say isn't pretty. Our passions are distorted as in funhouse mirrors. Our injuries are matched only by our fears. If you read Julius Caesar carefully, you can only conclude that Shakespeare's harshest judgement is not reserved for the budding despot Caesar, or the men who conspire to kill him, but for the masses so easily swayed, so impatient, so unfree in their thinking, so inadvertently eager to prove, as Cassius says to Brutus, "that we are underlings."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.