Women and girls stand to be particularly affected by President Donald Trump's executive order temporarily banning all refugees as well as all travelers from seven majority-Muslim countries, and indefinitely banning Syrian refugees. This shuts the door on female refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq and other countries where women's human rights are particularly vulnerable; the anti-Muslim nature of the ban also increases pressure on women wearing hijab in the U.S.

Syrian women face not only the physical insecurity of a deadly proxy war, but also the danger of ISIS and other religious extremist groups whose leaders seek to control women's bodies and their movements. This new policy closes the door on those women seeking refuge. Even the Yazidis of Iraq, the Christian minority group that has suffered the loss of thousands of women and girls who have been captured by ISIS and held as sex slaves, have been "denied boarding on U.S.-bound flights despite visas," reported NPR's Jane Arraf on Twitter.

Related: Read this former U.S. ambassador's letter to Nikki Haley on Trump's immigration ban

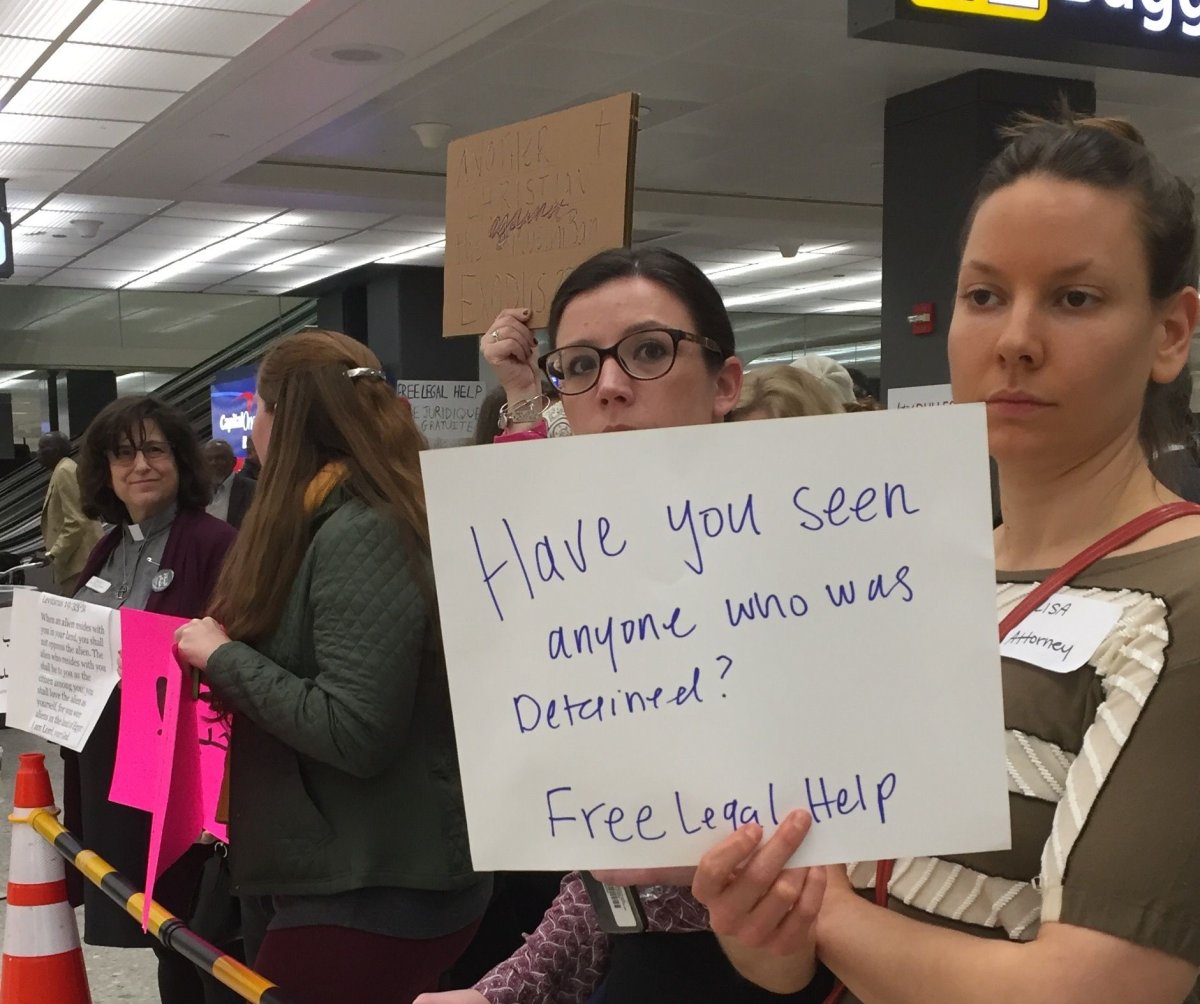

On Saturday and Sunday, thousands gathered at Dulles Airport in Virginia and in New York, Dallas, Chicago and elsewhere to protest the executive order. Meanwhile, Muslim-American women at Dulles—and their daughters—were at the forefront of a peaceful resistance movement.

"The executive order says that it doesn't want to let in people who support honor killings, but then [Trump] won't let in the women who are at risk of these honor killings," said Mirriam Seddiq, an Afghan-American criminal defense lawyer who fielded questions from the press on behalf of the hundreds of lawyers assembled. Seddiq stood in front of dozens of advocates camped out on laptops, surrounded by pizza boxes and tangerines meant to last them through the night. Many of the lawyers held signs that said, "Know someone who has been detained? I can help."

As a woman in hijab ushered her children through the narrow walkway at Dulles international arrivals, surrounded on both sides by hordes of Muslim-American families and lawyers, the crowd broke out singing, "This land is my land, this land is your land."

"What we've seen is that they are sending people to secondary detainment who are not just from the countries on the list, but from all Muslim countries and from Africa," said Sara Dill, a 37 year-old Muslim-American from Chicago and a lawyer with the American Bar Association, her tired face lined by a tightly wrapped bright yellow headscarf. Dill said of the ban on Syrian refugees to the U.S.: "the women and children coming out of Syria… have a dictator committing war crimes, they are coming out of this trauma…They had all of this hope that they were finally going to have safety and freedom, and they are being sent back."

"It's the same as always... they hide their bigotry and misogyny by saying it's only if they [Muslim women] aren't here yet," said Seddiq, who recently started the American Muslim Women Political Action Committee and says it is more important than ever to have Muslim women in elected office.

The Trump administration says that the executive order is not a ban on Muslims, but rather a measure to restore security to the U.S. In a statement on Sunday, President Trump said, "It's working out very nicely and we're going to have a very, very strict ban and we are going to have extreme vetting, which we should have had in this country for many years." The executive order states that, "In order to protect Americans, the U.S. must ensure that those admitted to this country do not bear hostile attitudes towards it and its founding principles… those who engage in bigotry or hatred (including "honor" killings, other forms of violence against women, or the persecution of those who practice religions different from their own)…"

The number of refugees that the US accepts is already a tiny fraction of the global burden: The U.S. admitted just 12,587 Syrians in 2016, compared to the 3 million that Turkey is hosting. Those familiar with refugee vetting say that it is a lengthy and rigorous process, and no person accepted as a refugee in the U.S. has been implicated in a major terrorist attack since the Refugee Act of 1980 set up detailed procedures for acceptance.

Hanging over the rope-lines at Dulles, Cansu Colakoglu, a young Turkish woman and graduate of Harvard Law School, asked passengers and pilots which flights they came off and whether any people had been detained. "People with headscarves were pulled out after passing customs to have a second inspections," she reported, pausing to high five with an Iranian-American woman walking out of customs. Muslim women who cover their hair are especially vulnerable to detainment, including those traveling with children.

Virginia Congressman Don Beyer, an advocate for women's issues in the House, arrived at Dulles on Sunday afternoon to advocate for detainees. "They aren't talking," he tweeted of Customs Border Control, while seeking the release of Sudanese green-card holder and Virginia resident Nahla Gadalla. After Beyer's questioning, Gadalla was released, although Border Control did not allow lawyers access to Gadalla or other detainees, according to Representative Beyer's office.

"Families are getting scared, headscarves are being pulled. The kids are scared," said Zainub (who declined to give her last name), a U.S. citizen from Pakistan in a peacock-blue headscarf. A teacher at an Islamic preparatory school in Reston, Virginia, she decided to protest at the airport in solidarity. Her ten-year old daughter, who had never before attended a protest, started a call and response with a willing crowd, shouting, "Show me what democracy looks like; This is what democracy looks like!" while Zainub filmed proudly.

Another mother from the same school, Samira, said her ten-year old daughter recently chose to start wearing a headscarf, a decision laden with meaning since January 20. "They don't understand why we wear it. They might think we are here to blow up the place," Samira said ruefully.

Xanthe Scharff Ackerman is the Executive Director and US Bureau Chief of the Fuller Project for International Reporting . Fariba Nawa is an award-winning journalist, reporting for The Fuller Project from Istanbul, and author of Opium Nation : Child Brides, Drug Lords and One Woman's Journey through Afghanistan.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.