Angela Merkel made "one very catastrophic mistake"—at least according to Donald Trump. Earlier this month, in an interview with The Times of London, Trump lambasted the German chancellor for admitting roughly a million refugees into her country—more than any other nation. While others praised Merkel's move as humane and compassionate, the New York real estate mogul said she created a potential security disaster.

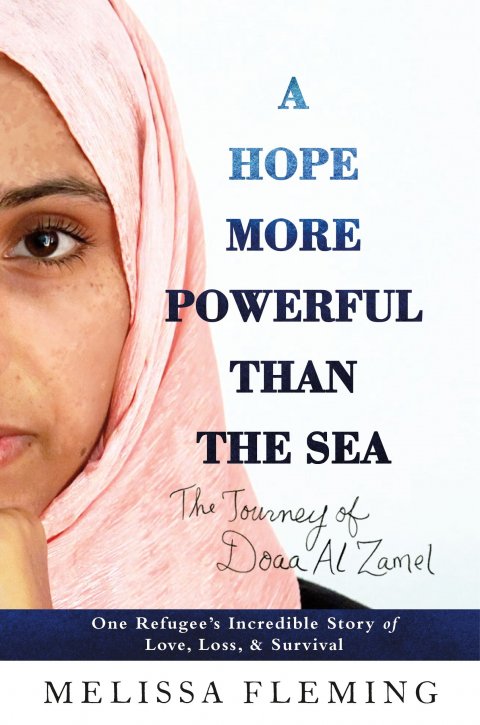

Trump's statement was galling, particularly because the war in Syria continues to rage and many Syrians remain imperiled. Those inside the country are desperate to escape, while many of those who have already crossed the border face a difficult future. In her new book, A Hope More Powerful Than the Sea, Melissa Fleming tells the story of one of those people, Doaa al-Zamel, a resilient young woman who is destined to become the Malala Yousafzai of Syria. Her story has the closest thing to a happy ending you can find in this bloody civil war.

Related: Reporter documents life in Aleppo

Al-Zamel comes from Daraa, a city close to the Syrian-Jordanian border. In 2011, a group of teenagers there lit the spark that engulfed the entire country in flames, spray-painting "You're Next, Doctor" on a wall. Their graffiti was a reference to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the events of the Arab Spring, which overthrew dictators in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt. The regime through them in prison and tortured them. They eventually let them go, but Syria would not be the same. Daraa became the birthplace of a revolution that quickly turned into a civil war.

Fleming documents with precise detail how quickly that war descended and took people by surprise, forcing their close-knit families and communities to disperse. One day they are gathered with their extended family celebrating Mother's Day, the next day there are tanks and snipers on the streets and they can hardly leave their home to buy bread. One day, Doaa's mother turns on the tap to make tea and no water comes out. Daraa, she later learns, has become a city besieged by the regime.

Like most refugees, the family doesn't want to leave their hometown, but Doaa's father decides it is unsafe for them to remain. He hears stories of girls being raped, and that compels him to flee with his wife and children. They cross the border into Jordan, drive to the Port of Aqaba and take a ferry to Egypt. People are initially kind in their host country, including the Muslim Brotherhood, which is the ruling party at the time. But the loss of status for Shokri, Doaa's father, a barber back in Syria, plunges him into depression.

Fleming deftly illustrates the pain of those who choose to leave Syria. They are alive, and they have managed to flee the conflict, but they are lost and adrift in their new home. Their old lives have vanished, and they must start anew with little more than what each can pack in a suitcase.

In 2014, Doaa falls in love with Bassem, a young Syrian refugee, but she rejects his marriage proposal. "I don't want to get married outside of Syria," she says. Her feelings change, as does the situation in Egypt. The people who welcomed them now catcall her in the street: "Hey, Syrian girl!" The connotation is sexual, sinister.

The couple sees little hope for their future. Not only do Syrians feel unwelcome, but work is scarce and, once again, people in Egypt begin to talk of revolution. "We're stuck," Bassem tells Doaa helplessly, convincing her they will have a better life in Europe. A friend of his went to Germany, he says. There, he believes, Doaa can go to school and he can open a barbershop. They can start a family.

Doaa is terrified of water and refuses to get in a boat. But Bassem assuages her, convincing her their passage will be safe. Their life in Berlin or Amsterdam, he explains, will be far better than it has been on the margins in Cairo.

But everything goes wrong. The year they leave for Europe, 2,000 refugees and migrants had already lost their lives crossing the Mediterranean. The main reason for the crisis is the war in Syria. Their journey to the continent begins with meetings with a nebulous smuggler, after which the couple is robbed and thrown in prison. Yet their journey continues.

They are 19 hours from the Italian coast when a group of pirate smugglers rams their boat. "Dogs!" the pirates shout. "You should have stayed to die in your own country." The next chapter is a glimpse of hell, with corpses floating in the water and children struggling to stay alive. Doaa survives, but Bassem does not make it.

Fleming recounts their narrative with compassion and without melodrama, and her book is ultimately a story of hope. Doaa arrives in Europe and recovers. She is plagued by nightmares and trauma, but she is able to move on, to learn to love life anew. When Fleming, in her capacity as director of communications for the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, meets her in 2015, she realizes the young woman is entrusting her with her story "to help her and her family resettle into another country and to warn other refugees who were tempted to make the same dangerous journey."

The message is to try to humanize one young woman, to tell her tale so that the migrant crisis does not become a bunch of nameless, faceless people fleeing a war but human beings with families, with needs, and with desires. Fleming does this by weaving in the history of the war and the reaction from countries around the world—but doing so while aware of how easy it is for readers to feel fatigued by despair.

Doaa ultimately reunites with her family (they are now living in Sweden). But there are still 4.8 million Syrian refugees who have fled to Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Iraq, and 6.6 million are internally displaced within Assad's war-torn nation. Meanwhile, about 1 million have requested asylum in Europe.

It's winter now, so the refugee boats are mostly dormant at the docks. But as soon as the weather warms, the smugglers—and their desperate clients—will be prepared to take a chance, simply to restore their sense of dignity.

Donald Trump, with his purported compassion for the underclass, would do well to read this book.