The telegram was one of the first to arrive from a world leader. On the morning of November 9, the Kremlin announced that Russian President Vladimir Putin had sent a message to U.S. President-elect Donald Trump expressing "his hope they can work together toward the end of the crisis in Russian-American relations, as well as address the pressing issues of the international agenda and the search for effective responses to global security challenges." Just minutes before, the Russian State Duma had erupted in applause when its members learned that Trump had won the election.

Putin appeared to be taking his lead from repeated comments Trump has made suggesting the two would get along: "I would treat Vladimir Putin firmly, but there's nothing I can think of that I'd rather do than have Russia friendly, as opposed to the way they are right now, so that we can go and knock out ISIS with other people," the then-candidate of the Republican Party said on July 28, referring to the Islamic State militant group.

But the blossoming bromance between the two men may come to a sudden end when Trump becomes commander in chief on January 20, 2017. That's when he will, on a daily basis, have to cope with a resentful former superpower engaged in an aggressive campaign of espionage and propaganda against the United States and its allies—one more intense and menacing than at any time since the Cold War. Trump will likely face a binary choice: continue to engage in that intensifying shadow war, as his predecessor chose to do, or end sanctions against Russia—essentially allowing Putin to expand his influence in Eastern Europe and beyond.

The pressure on Trump to come up with an answer will be considerable. In early November, Andrew Parker, head of Britain's internal security service MI5, became the first leader of the agency in 107 years to give an interview; the focus of his conversation with The Guardian newspaper was Russia's mobilization of "a whole range of state organs and powers to push its foreign policy abroad in increasingly aggressive ways: propaganda, espionage, subversion and cyberattacks." Russia's secret war involves everything from criminal sabotage to espionage to influencing news cycles, as well as supporting disruptive political movements and deep penetration of cyberinfrastructure. That's a lot for an American president who has never before held elected office to deal with on day one.

With Trump's victory, Russia might feel that its potent mixture of hacking, propaganda and sowing distrust has worked spectacularly well. The temptation to continue spreading chaos by backing right-wingers in France, the Baltics, Germany and elsewhere is stronger than ever. "Putin has interfered in our elections and succeeded. Well done," tweeted former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul after Trump's victory. And Russia's elite, while careful to deny involvement in the Kremlin's alleged meddling in the U.S. presidential race, is openly jubilant about Trump's win. "First was Brexit. Now Hillary," says Russian parliamentarian Vyacheslav Nikonov, a Putin ally. "A while ago, America was saying that Russia is just a gas station, a regional power. Now, apparently, we're so influential that we are determining the outcome of their presidential election. We follow the ancient Chinese policy—we sit on the riverbank and wait for our enemy's body to float past."

But Russia isn't just sitting and waiting. It is actively engaging its enemies, albeit in clandestine ways. The Kremlin's shadow war has intensified since Russia's annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and the international sanctions that followed. That was the moment it began to "define itself by opposition to the West and act accordingly," MI5's Parker told The Guardian. "Russia has been a covert threat for decades. What's different these days is that there are more and more methods available…. There is high-volume activity out of sight with the cyberthreat."

Russia has spearheaded some increasingly bold and sophisticated operations over the past year, including hacking attacks on Ukraine's power grid and the servers of the White House, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Germany's Bundestag that Western intelligence agencies believe came from Russia. Western governments are belatedly waking up to the scale of the threat and are readying the biggest counterespionage operation since the end of the Cold War. Spy agencies have pivoted with urgency. When the decades-long nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union and its allies came to an effective end with the demise of the Soviet empire in 1991, Western intelligence and security agencies largely turned their attention and resources elsewhere—especially to the Middle East and Afghanistan, as Islamist extremists' attacks appeared to become the greatest threat to the West. That challenge remains. But the Russian threat is back.

The Kremlin's new army of spooks is motivated by a single ideology—to fight back against a supposed Western campaign to undermine Russian power and foment unrest and revolution in Moscow's backyard. Bizarre as this may seem to American and European observers, the majority of Russians—crucially, Putin and his inner circle—are convinced that the pro-democracy revolutions that swept Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan in 2003 and 2004, the mass protests in Moscow against Putin in 2012 and the uprising in Kiev against pro-Moscow President Viktor Yanukovych were all part of a CIA-led conspiracy to weaken Moscow. "This is not just laughable rhetoric but an expression of a genuine belief," says Mark Galeotti, a senior research fellow at the Institute of International Relations in Prague. "When Moscow identifies all kinds of NGOs as 'foreign agents,' this is not only a convenient way to silence and marginalize critics. It also reflects a conviction that the West supports investigative journalists and anti-corruption movements in Russia not on their own merits but to undermine the regime."

Russia's spying operations, therefore, are justified as a part of a major pushback against perceived aggression. "You Americans meddled in our elections for years; now we meddle in yours. How do you like it?" wrote Ekaterinburg-based blogger Evgeny Smirnov in September. "You say we are influencing your politics with our propaganda. Yes—just as you taught us!"

Preventing further Russian meddling in American politics will become the problem of a president-elect whose true feelings about Russia, Putin and just about every other major policy area remain opaque. Sure, in the days following Trump's victory, Russia's television talk shows were full of clips of the president-elect's warm words about Putin. Trump called Putin a "stronger leader" than outgoing U.S. President Barack Obama and told ABC in July that "the people of Crimea, from what I've heard, would rather be with Russia than where they were." Asked by a reporter in July whether he would consider recognizing Crimea and lifting sanctions, Trump replied, "Yes, we would be looking at that," sparking jubilation in Moscow. Gennady Zyuganov, veteran leader of Russia's Communist Party, tells Newsweek he sees Trump as "a candidate of peace, not war, who will respect the interests of Russia and stop [the last administration's] aggressive encroachment on our borders."

But Trump has also blasted Putin. "Russia took Crimea during the so-called Obama years," Trump tweeted in September. "Who wouldn't know this, and why does Obama get a free pass?" And Russia's optimism about the end of sanctions is also misplaced; His "Yes, we would be looking at that" response is, as many reporters pointed out, just a line Trump often uses to move on to the next question. Russian hackers may have helped Trump to victory. But if and when Trump disappoints the Kremlin—perhaps by bowing quickly to congressional Republicans' strong support for Ukraine in its fight against Russian-backed separatists—the 45th president of the United States could find himself facing off against the same ruthless adversary in Moscow who made life so hard for the 44th. And the 43rd. And the 42nd.

Hybrid Warfare

If Trump is looking for a reminder of the real-world damage Putin's online special forces can cause, he might want to ask the CIA for a briefing on a cyberattack that began on December 23, 2015. A winter's early dusk was falling over the Ivano-Frankivsk region in western Ukraine when Russian hackers took control of the electricity grid. Controllers at the headquarters of the local energy utility, PrykarpattyaOblEnergo, watched helplessly as they were locked out of their computers. Cursors began operating on their own, clicking circuit breakers in the utility's central command system, shutting down electricity substations one by one. Within half an hour, 700,000 residents, as well as hospitals and schools, were without power. That marked the start of the biggest and most sustained cyberattack against any nation ever conducted. Over the following nine months, according to the Ukrainian Security Service, hackers made more than 15,000 other attempts to sabotage Ukraine's critical infrastructure, from the control systems at Kiev's Boryspil International Airport to the country's Central Election Commission. So far, nobody has died as a result of the cyberassault—but the attacks proved the hackers could shut down operating rooms and airports at will.

"A clear Rubicon was crossed," says Alexander Klimburg, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council think tank in Washington and author of the upcoming book The Dark Web, which describes how future conflicts will be fought over the internet. "Cyberweapons have officially joined the arsenal of modern warfare."

Putin has apparently tasked Russia's securocrats with doing what Soviet spies dreamed of but could never achieve—fighting a war of covert disruption in parallel to their more traditional role, straight intelligence-gathering. The strategy is laid out in the latest version of Russia's official military doctrine. A key task of modern so-called hybrid warfare is "the prior implementation of measures of information warfare in order to achieve political objectives without the utilization of military force and, subsequently, in the interest of shaping a favorable response from the world community to the utilization of military force." To that end, all the state's resources—led by Russia's security services—are responsible for "developing forces and resources for information warfare."

Aric Toler, an American researcher at the activist group Bellingcat, has been on the receiving end of that information war machine. Founded by British blogger Eliot Higgins in 2014, Bellingcat has used open-source material, such as social media posts and YouTube video footage, to expose Russian troops operating illegally in eastern Ukraine and, most controversially, to precisely track the course of a Russian Army BUK rocket launcher that shot down Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over eastern Ukraine on July 17, 2014. It was Russia's involvement in the shooting down of MH17 and its subsequent stonewalling over the investigation that became the main focus of biting EU and U.S. sanctions on the Russian economy—not, as Russia often claims, its annexation of Crimea. Moscow has continued to deny its BUK rockets were involved—blaming the crash on, variously, Ukrainian jets or Ukrainian surface-to-air missiles. But Bellingcat's evidence, from dozens of sources tracking the BUK's progress into and out of eastern Ukraine on that fateful day, is more than just the work of internet geeks. Official Dutch and Malaysian investigators are using it to draw up formal charges against the Russian soldiers and officials responsible. The British bloggers have exposed attempts to cover up the truth on MH17—and in the process helped deny the Russian economy billions of dollars in investment. No wonder the Kremlin appears to have gone after Bellingcat with such ferocity.

Over the past 18 months, Toler has regularly received phishing emails containing viruses that would allow hackers to access his computer—if any of us were dumb enough to click on the links." More threatening, over the summer pro-Russian online activist group CyberBerkut hacked into the emails of Ukrainian government officials and used the information to smear Toler by alleging he is linked to the Kiev government. Finally, Russian state-sponsored TV channels, like Russia Today and Sputnik, keep up a regular stream of invective against Bellingcat's work, while a small army of trolls on Twitter and social media are busy denouncing it on an hourly basis.

"We've been targeted by the full force of the Russian information machine," says Toler. "We can't say for sure if these are Russian government or proxy groups...but the phishing emails [we received] are the same as those which targeted the Democratic National Committee."

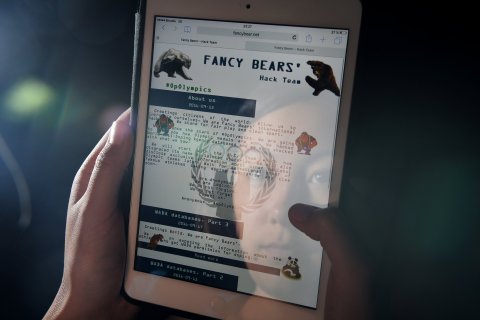

In June, Russian hackers gained international notoriety by breaking into the email database of the DNC and releasing emails embarrassing to Hillary Clinton. The hacker groups behind the break-in, APT 28 and APT 29 (or more snappily nicknamed Cozy Bear and Fancy Bear by U.S. cybersecurity companies) are in fact two operations linked, respectively, to Russia's Federal Security Service, or FSB, and Russian military intelligence, or GRU. James Clapper, the U.S. director of national intelligence, has launched an investigation into alleged Russian operations against the U.S. presidential election.

The incoming American president would do well to consider that while the DNC hack might have helped him during the election campaign, Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear later showed they have a broad range of targets. In September, the groups were linked to the release of sensitive data stolen from the World Anti-Doping Agency that revealed that several top Western athletes—including U.S. tennis stars Venus and Serena Williams—had been given exemptions for taking prohibited drugs during the Olympics, while a swath of Russian athletes had been banned for illegal drug use. Later that month, the groups leaked emails from General Philip Breedlove, NATO's former supreme allied commander for Europe, that suggested his dissatisfaction with some European allies and then released first lady Michelle Obama's passport and sensitive travel information from the White House. To cap off a busy U.S. election season of hacking, Fancy Bear in October leaked a series of emails from former Secretary of State Colin Powell in which he allegedly said, "I would rather not have to vote for [Hillary]" and described Clinton as having "a long track record [of] unbridled ambition, greedy, not transformational."

It's enough to make an incoming president and his aides wonder whether the Kremlin is already reading in on the transition plans.

Crooks and Spooks

If Russian hackers launch fresh attacks on the U.S. after January, the new president will likely face flat denials of involvement from the Kremlin—and he and U.S. intelligence officials will struggle to provide evidence to back up their claims of state involvement, say Western intelligence sources and computer security experts. That's because Russia's spies have formed an alliance with the country's notorious cybercriminals—and the spooks use the crooks as cover. "At least half" of the Kremlin-backed hackers' arsenal "is derived from cybercrime, perhaps much more," says internet security expert Klimburg. The partnership between Russian criminals and Russian spies goes back as far as 2007, when hackers known collectively as the Russian Business Network deployed computers they had infected with Trojan horse viruses and turned them into a network of zombified machines known as botnets to bombard and shut down internet servers in Estonia. The attack was apparent punishment for Estonia taking down a monument to a Red Army soldier. Just as with the DNC hack, the Kremlin indignantly denied responsibility. But subsequent investigations linked the attack to, variously, the pro-Kremlin youth group Nashi and a former parliamentary aide. A clear chain of command was never established—but the pattern was: The cybercriminals had become the Kremlin's cyber hatchet men.

"It's not unprecedented for governments to use criminals to do their dirty work. Back in the day, [French President Charles] de Gaulle used the Corsican Mafia against the [ultranationalist] OAS; the CIA used the Italian Mafia against the Cubans," says a senior U.K. security official not authorized to speak on the record. "But most of us thought that kind of thing has been left behind with the Cold War—along with poisoning defectors and the like. We've been proved quite wrong on both counts."

In October, a Russian hacker was arrested in Prague on an Interpol warrant issued after an investigation by the FBI. Identified by Czech police only as Yevgeniy N., the hacker was busted for his involvement in a massive 2012 break-in at LinkedIn, a company spokesman told Reuters, which compromised the credentials of 100 million users, prompting the company to launch a massive password reset operation. According to one cyberexpert who advises Western governments, Yevgeniy N. is of special interest to law enforcement because of suspicions that the information he gathered during his hacking career "cropped up in later hacks that we believe are clearly [Russian] state-sponsored."

Multiple spy agencies are involved in Russia's full-spectrum assault—and some of them are growing rapidly. The FSB is Russia's largest security agency—and will, according to a document leaked to the Russian Kommersant Daily in September, soon become larger, thanks to its plan to create a new super-ministry of state security. The Kremlin's Presidential Administration is the most influential agency involved in Russia's shadow war, says Galeotti, coordinating traditional spies controlled by Russia's External Intelligence Service, or SVR, alongside propaganda operations run by state-funded media outlets, such as Sputnik and the RT English-language television news channel, formerly Russia Today, which is available to 700 million people in more than 100 countries around the world. The SVR's headquarters, in the Yasenevo district of Moscow, has doubled in size since 2007, as images posted online by transparency activist Steven Aftergood of the Federation of American Scientists' Secrecy News blog clearly show.

And it's not just computer geeks who are filling the desks and offices inside. Russia's old-school spies are working to undermine the West as much as, if not more than, their Soviet predecessors. According to John Bayliss, a former official at Britain's electronic surveillance agency, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), "There are more Russian intelligence agents [in the U.K.] now than at the height of the Cold War."

The chief analyst of Sweden's SAPO intelligence service, Wilhelm Unge, warned in October that a third of all Russian diplomats stationed in Sweden are intelligence officers, far more than during the 1980s, and that Russia constitutes "the biggest intelligence threat against Sweden." In May, a Warsaw military court convicted a Polish army lieutenant-colonel for passing information about soldiers with disciplinary problems to a Russian handler (prosecutors claimed that servicemen in trouble with the authorities were easier to recruit). In October, Montenegro's long-serving, pro-Western prime minister, Milo Djukanovic, claimed he'd been the victim of an attempted coup with a "strong foreign connection." Montenegro's security forces arrested 20 Serbs and Montenegrins on October 16, and Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic confirmed that the men arrested in Montenegro had hatched their coup plot in Serbia, assisted by Russian intelligence. An indignant Vucic said he would not allow his country to "act as the puppet of world powers."

There's no proof linking the Kremlin to the Montenegrin coup plotters—but there is plenty of evidence that there has been a major uptick in Russian efforts to meddle in the internal politics of a range of European countries. Last month, the Czech Republic's BIS intelligence agency accused Russia of not just spying but also of "creating or promoting inter-societal and inter-political tensions" in the country, including covert support for domestic extremist and populist organizations that "tend to hold consistently pro-Russian stances on domestic and international issues. They are also highly critical of NATO and the EU, and promote the view that, like Britain, the Czech Republic should seek to exit the EU." Czech intelligence's annual report caused a sensation when it was published in September, because it stated bluntly that the Kremlin's aim was to "destabilize or manipulate Czech society at any time, if Russia wishes to do so."

Moscow has also been actively reaching out to France's National Front, whose anti-immigrant, anti-EU leader, Marine Le Pen, has become a hero on Russian media. The National Front confirmed that it had borrowed 9 million euros from the Moscow-based First Czech Russian Bank in 2014, while in February of this year the party's treasurer, Wallerand de Saint-Just, made no secret of the fact that he was seeking up to 23 million euros from "any other" Russian banks that would be willing to stump up. At a private pro-Trump election party I attended in an English-themed pub in downtown Moscow, three specially commissioned portraits stood in pride of place: Trump, Putin and Le Pen. Le Pen has called for sanctions on Russia to be lifted and for a deal to build two Mistral-class warships for Moscow—blocked by French President François Hollande under strong U.S. pressure in the wake of the Crimea annexation—to go ahead.

"We are entering a new era of politics," says political scientist Sergei Mikheyev. "Europe will be free to think for itself instead of obeying Washington's Russophobia. Le Pen is a patriot who is ready to defy American diktat."

Le Pen will be a candidate for the French presidency in the spring of 2017. She is expected to do well—but, like Trump at a similar stage of the electoral cycle, nobody is expecting her to win.

Best Frenemies

The West is starting to fight back against the Putin threat—and Trump will find himself in charge of the effort to combat the man he has called "very much a leader." This month, the U.S.'s most important ally—the U.K.—announced a new £1.9 billion national cybersecurity strategy designed to develop what Finance Minister Philip Hammond called a "fully functioning cyberattack capability" to be able to "match the cyberattack abilities of foreign rogue states." Britain is opening a new cyberinnovation center and scaling up its security services by recruiting 1,900 additional staff. And intelligence agency MI6, which employs around 2,500 people, is set to receive over half of those new personnel. "The areas of expansion are obviously internet resources like social media, plus the use of facial recognition technology," for intelligence gathering, says one former Secret Intelligence Service staffer with knowledge of the expansion plans. "The emphasis has changed from just running agents like in the past." But even with the new recruits, Russia will have more than six intelligence officers for every British spook, according to Bayliss, the former GCHQ officer.

There's also been a scramble across Western intelligence services to recruit and train Russian experts. For the first time since the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991, the U.S. has diverted resources from counterterrorism to counterespionage to push back against Russia, according to Evelyn Farkas, a top Russia official at the Pentagon until his retirement in 2015. "The Russia beat for intel folks was a more quiet one, frankly speaking, over the last couple decades," Farkas told NPR recently. "And now it's quite hot. And we have to find linguists. We have to find people who can analyze all the information that we have to find coming in, in Russian and other languages."

Trump is unlikely to ask America's intelligence agencies to give up recruiting Russian-speakers and let Putin have his way. And it's entirely possible that by the time he is inaugurated, the new president will have concluded that the affinities he shares with Putin are really only slogan-deep. Both may harbor a strong nostalgia for postwar glory days when, as Trump told an interviewer in March, "we were not pushed around. We were respected by everybody. We had just won a war." Both may espouse social conservative rhetoric, claim a distrust of educated elites and rely on the support of the American and Russian working classes. But in the Venn diagram of American and Russian interests, there's not a huge overlap.

Moscow is trying to disrupt and fragment Europe, but it's in the U.S.'s interest to keep Europe prosperous, united and at peace. In Syria, Russia would like to demonstrate that its military and diplomatic support can keep despotic client leaders like Bashar al-Assad in power—while the U.S. has always insisted that Syria must have democratic elections that include all non-jihadi opposition groups. The Kremlin would like to once again make Ukraine a client state—or, failing that, cripple the country by sponsoring an ongoing civil war to prevent it from joining the EU and becoming a post-Soviet success story. But congressional Republicans—working in parallel with the Obama White House—have always strongly supported the struggle of what Senator John McCain calls "the captive nations" against their former Russian overlords.

And then there's the Baltics, a corner of northeastern Europe Trump may not have spent much of his career thinking about. It's in the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—all once constituent parts of the U.S.S.R. with large ethnic Russian populations—that Trump's potential chumming up with Putin could have its first tragic consequences. Trump has called NATO "obsolete and extremely expensive" and has suggested he would not honor NATO members' commitments on collective defense unless other alliance members pay their fair share. If he repeats that rhetoric, let alone implements it, Putin could order his troops or local proxy forces to attack or destabilize the Baltic states—all of them members of NATO—under the pretext of protecting fellow ethnic Russians. "I really hope that the rhetoric on defense and Russia was mostly a part of the election campaign," Saulius Skvernelis, Lithuania's incoming prime minister, said in an interview with Reuters on November 9. "I hope the election campaign is now over and it is not yet time to panic."

The coming months will likely show Skvernelis whether his hopes are justified. If he gets lucky, he'll watch the former reality-TV star rapidly figure out who America's allies are—and how important it is to protect pro-American countries like Lithuania. "It is a very imperfect world, and you can't always choose your friends," Trump said in September. "But you can never fail to recognize your enemies."

The next president has only a few more weeks to figure out whether Putin is a friend or a foe.