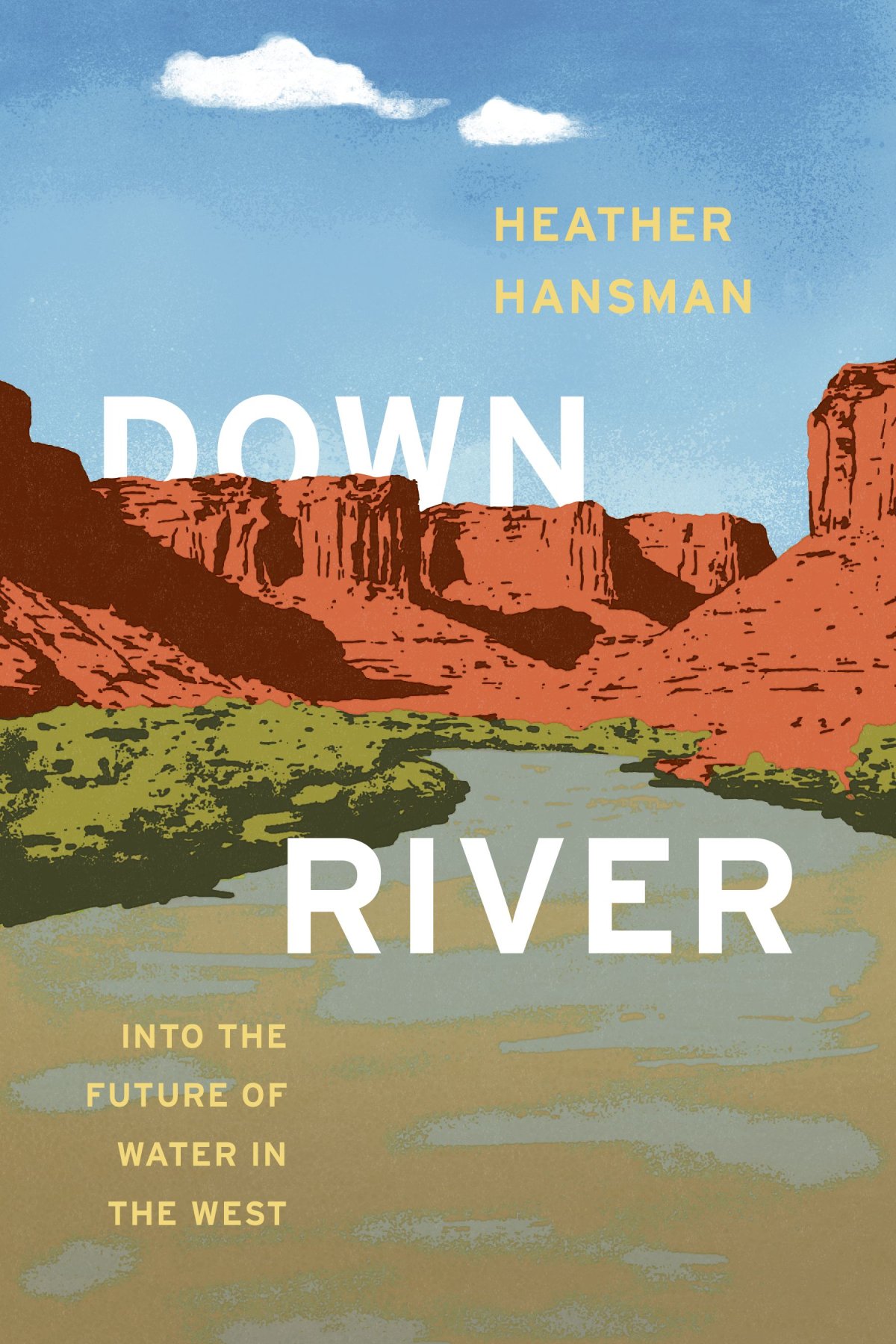

In her new book, Downriver, Heather Hansman paddles the length of the Green River—the biggest tributary of the Colorado River, which brings water to 40 million people in the Western U.S., to look at how ranchers, cities, raft guides, and fight about water, and what's going to happen to those battles in a hotter, drier, more crowded future. This is an excerpt from the book.

In Desolation Canyon, Wire Fence and Three Fords rapids come one after another, with hardly enough beach space in between to collect yourself after the first wave train. The shore is thick with tamarisk, so we stop high above the rapid and hike downstream along a deserty overgrown ridge to scout them both. As we stand on the shore watching water pile up, my stomach drops. I've brought my parents to this stretch of the Green River, deep in the empty Utah desert to show them why rivers have become a driving force in my life, but part of that comes with trying to keep them safe as I row us downstream. Both rapids are channelized and rock studded. The margin for error at Wire Fence is narrower, but Three Fords pushes hard against a rock wall on the right side so that you have to fight the current to avoid getting pinned up against the rocks. I hike back upstream silent, visualizing the markers I've picked out for myself, trying to run through the lines in my head, but the memories have almost faded by the time I get back to the boat.

We push off, and I pull against the persistent up-canyon wind, fighting to line myself up for the channel. Rowing a heavy oar boat takes both patience and fast-twitch, spilt-second reflexes. You have to set your angle early and let the river take you—you can't fight it all the time—but you also have to be ready to react and know when to ship your oar and when to pry against the current.

The river compresses into wave trains and pours into holes, bending around eroding corners of the canyon. Most of the technical rapids in Desolation are class III, depending on the water level. Nothing too scary, just enough to make you constantly vigilant, especially with the burden of never having seen that stretch of river before, and of trying to be protective. I don't know the strength of the holes, or whether they're powerful enough to flip a boat.

We hit the tongue of water just left of a marker rock in the middle of the channel, and I push hard to the center to avoid the diagonal wave echoing off the right shore. I punch the wave, spinning to hit it straight on. The boat sucks back a bit, then pushes free. Suddenly I'm rowing for the middle of the channel, clean.

Then, river bellies around a bend to the right, and quickly drives back left, building into the compression waves of Three Fords. In the slack water above the rapid I fight the urge to recalibrate. I'm looking for my markers at the top of the rapid. I nose just right of the guard rock, exactly where I want to be, then jam my oar against the rock, throwing it out of my hand, and pushing us off line, sucking our boat sideways toward the biggest wave. Suddenly everything is happening too fast. I flail and finally find the oar and straighten out in time to hit the second hole head on. From there it's just rock dodging, the kind of river running that feels like a video game. I get a "Good job, kiddo" from my dad, who never calls me kiddo.

We float on, into the mouth of Gray Canyon, past the last pikeminnow spawning bar, where endangered fish lay their eggs, into a lower, craggier landscape. It's a break of flatwater before the next set of rapids we'll need to scout, and we crack beers to celebrate, even though it's before noon. So much of paddling whitewater is calculating risk: planning for what you can't see by reading the bubble line leading over the edge of the rapid, trying to commit the dangerous parts to memory so that you don't get sucked into them, and trying not to hurt other people along the way.

Water management is risk management, too, and here, on the Green—the biggest tributary of the Colorado River, which brings water to 40 million people across the west—we're at a crucial point of jeopardy. We're using more than exists, and climate change is predicted to shrink the flow 50 percent by the end of the century, cutting off our supply.

That's why I'm here. This section is a slice of my downriver journey. I'm paddling the length of the river, to try and understand that risk, my own and other people's, and to see, from river level, what we could stand to lose if we don't change how we use and allocate water. "Throughout the whole last century, if you needed more water it always worked out somehow, but it doesn't work when you get to the point where you're storing every last drop," Doug Kenney, Director of the Western Water Policy program at the University of Colorado, tells me before I set out on the river. "You have to talk people through it, and explain that for every new reservoir you try and fill you're putting more stress on the other parts of the system. Things are changing and we should behave in a way that limits our risk."

I'm starting to think that the undercurrent of risk is an important driver; it galvanizes people. We're going to have to grapple with how much risk is reasonable, and who bears the burden of it, when climate change cuts into supply and demands grow.

The canyons dip and curve, forming amphitheaters, hoodoos, and spires. The walls are striated, striped tan, green-gray, and very black. They funnel the wind, which picks up in the afternoon. We fight it through the day's last few sections of rapids, constantly getting pushed upstream, until we find a flat, protected beach, but even the battle is beautiful. The light starts to take on a low evening slant, which comes slowly this time of year. We swim a little, then boil water for pasta and talk about the day, the grip of fear in the gnash of whitewater, the adrenaline rush of running through it cleanly, the fragile balance of what we might stand to lose.

Heather Hansman is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in Outside, California Sunday, Smithsonian, and many other publications. After a decade of raft guiding across the United States, she lives in Seattle.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.